Unitarians Join The Organ Revival Movement

Unitarians Join The Organ Revival Movement

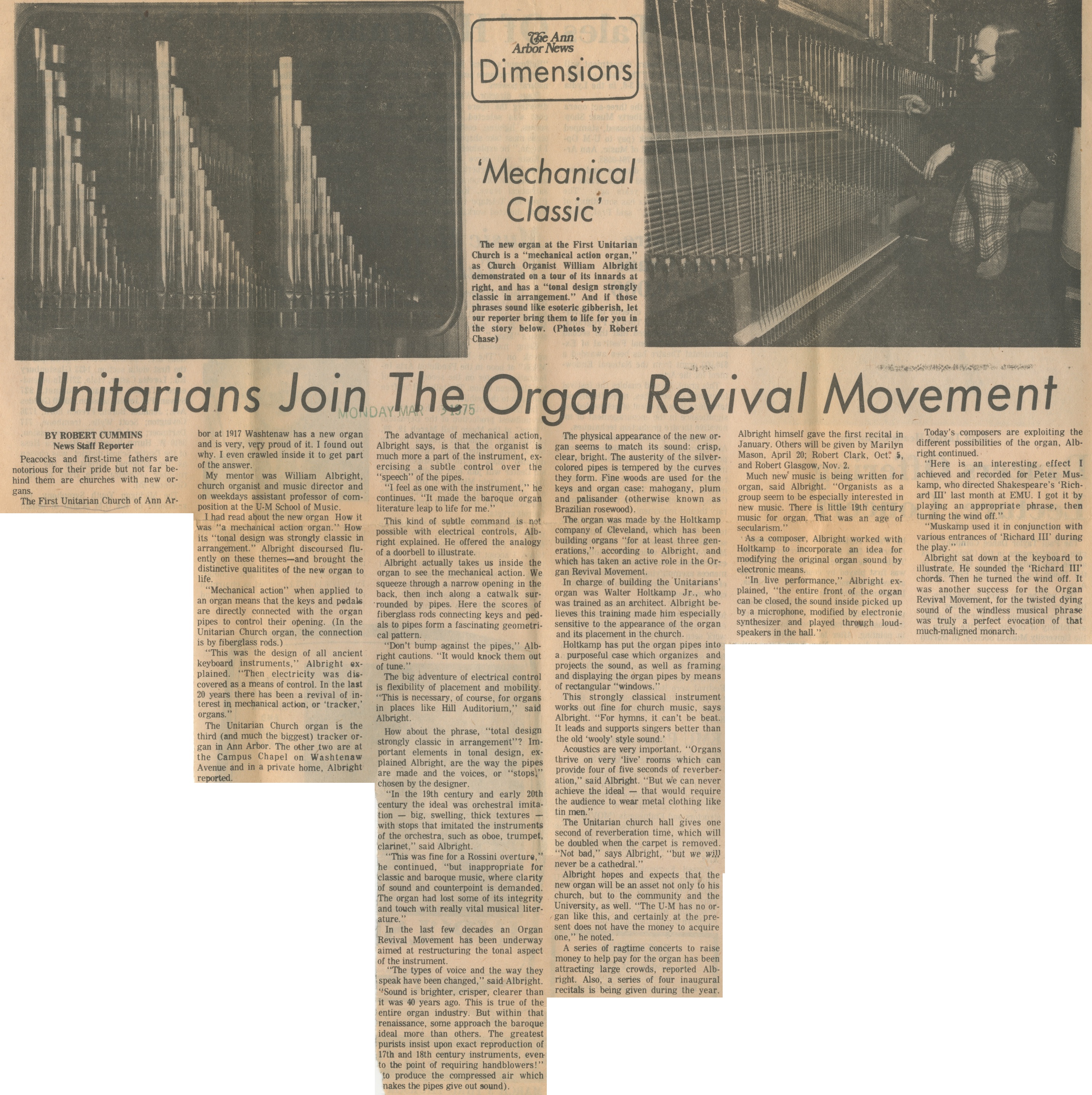

"Mechanical Classic'

The new organ at the First Unitarian Church is a "mechanical action organ," as Church Organist William Albright demonstrated on a tour of its innards at right, and has a "tonal design strongly classic in arrangement." And if those phrases sound like esoteric gibberish, let our reporter bring them to life for you in the story below (Photos by Robert Chase)

BY ROBERT CUMMINS

News Staff Reporter

Peacocks and first-time fathers are notorious for them pride but not far behind them are churches with new organs.

he First Unitarian Church of Ann Arbor at 1917 Washtenaw has a new organ and is very, very proud of it. I found out why. I even crawled inside it to get part of my answer.

My mentor was William Albright, church organist and music director and on weekdays assistant professor of composition at the U-M School of Music.

I had read about the new organ How it was "a mechanical action organ." How its "tonal design was strongly classic in arrangement." Albright discoursed fluently on these themes - and brought the distinctive qualities of the new organ to life.

"Mechanical action" when applied to an organ means that the keys and pedals are directly connected with the organ pipes to control their opening. (In the Unitarian Church organ, the connection is by fiberglass rods.)

"This was the design of all ancient keyboard instruments," Albright explained. "Then electricity was discovered as a means of control. In the last 20 years there has been a revival of interest in mechanical action or 'tracker,' organs.

The Unitarian Church organ is the third (and much the biggest) tracker organ in Ann Arbor. The other two are at the Campus Chapel on Washtenaw Avenue and in a private home, Albright reported.

The advantage of mechanical action, Albright says, is that the organist is much more a part of the instrument, exercising a subtle control over the "speech" of the pipes.

"I feel as one with the instrument," he continues. "it made the baroque organ literature leap to life for me."

This kind of subtle command is not possible with electrical controls, Albright explained. He offered the analogy of the doorbell to illustrate.

Albright actually takes us inside the organ to see the mechanical action. We squeeze through a narrow opening in the back, then inch along a catwalk surrounded by pipes form a fascinating geometrical pattern.

"Don't bump against the pipes," Albright cautions. "It would knock them out of tune."

The big adventure of electrical control is flexibility of placement and mobility. "This is necessary, of course, for organs in places like Hill Auditorium," said Albright.

How about the phrase, "total design strongly classic in arrangement"? Important elements in tonal design, explained Albright, are the way the pipes are made and the voices, or "stops," chosen by designer.

"In the 19th century and early 20th century the ideal was orchestral imitation-big, swelling, thick texture - with stops that imitated the instruments clarinet," said Albright

"This was fine for a Rossini overture," he continued, "but inappropriate for classic and baroque music, where clarity of sound and counterpoint is demanded. The organ had lost some of its integrity and touch with really vital musical literature.

In the last few decades an Organ Revival Movement has been underway aimed at restructuring the tonal aspect of the instrument.

"The types of voice and the way they speak have been changed," said Albright. "Sound is brighter, crisper, clearer than it was 40 years ago. This is true of the entire organ industry. But within that renaissance, some approach the baroque ideal more than others. The greatest purists insist upon exact reproduction of 17th and 18th century instruments, even to the point of requiring handblowers!" (to produce the compressed air which makes the pipes give out sound).

The physical appearance of the new organ seems to match its sound: crisp, clear, bright. The austerity of the silver colored pipes is tempered by the curves they form. Fine woods are used for the keys and organ case: mahogany, plum and palisander (otherwise known as Brazilian rosewood).

The organ was made by the Holtkamp company of Cleveland, which has been building organs "for at least three generations," according to Albright, and which has taken an active role in the Organ Revival Movement.

In charge of building the Unitarians' organ was Walter Holtkamp Jr., who was trained as an architect. Albright believes this training made him especially sensitive to the appearances of the organ and its placement in the church.

Holtkamp has put the organ pipes into a purposeful case which organizes and projects the sound, as well as framing and displaying the organ pipes by means of rectangular "windows."

This strongly classical instrument works out fine for church music, says Albright. "For hymns, it can't be beat. It leads and supports singers better than the old 'wooly' style sound.'

Acoustic are very important. "Organs thrive on very 'live' rooms which can provide four of five seconds of reverberation," said Albright. "But we can never achieve the ideal - that would require the audience to wear metal clothing like tin men."

The Unitarian church hall gives one second of reverberation time, which will be doubled when the carpet is removed. "Not bad," says Albright, "but we will never be a cathedral."

Albright hopes and expects that the new organ will be an asset not only to his church, but to the community and the University, as well. "The U-M has no organ like this, and certainly at the present does not have the money to acquire one," said noted.

A series of ragtime concerts to raise money to help pay for the organ has been attracting large crowds, reported Albright. Also, a series off our inaugural recitals is being given during the year.

Albright himself gave the first recital in January. Others will be given by Marilyn Mason, April 20; Robert Clark, Oct. 5, and Robert Glasgow, Nov.2.

Much new music being written for organ, said Albright. "Organists as a group seem to be especially interested in new music. There was an age of secularism."

As a composer, Albright worked with Holtkamp to incorporate an idea for modifying the original organ sound by electronic means.

"In live performance," Albright explained, "the entire front of the organ can be closed, the sound inside picked up by a microphone, modified by electronic synthesizer and played through loudspeakers in the hall."

Today's composer are exploiting the different possibilities of the organ, Albright continued.

"Here is an interesting effect I achieved and recorded for Peter Muskamp, who directed Shakespeare's 'Richard III' last month at EMU. I got it by playing an appropriate phrase, then turning the during the play."

Albright sat down at the keyboard to illustrate. He sounded the 'Richard III' chords. Then he turned the wind off. It was another success for the Organ Revival Movement, for the twisted dying sound of the windless musical phrase was truly a perfect evocation of that much-maligned monarch.