Feiner's At 100

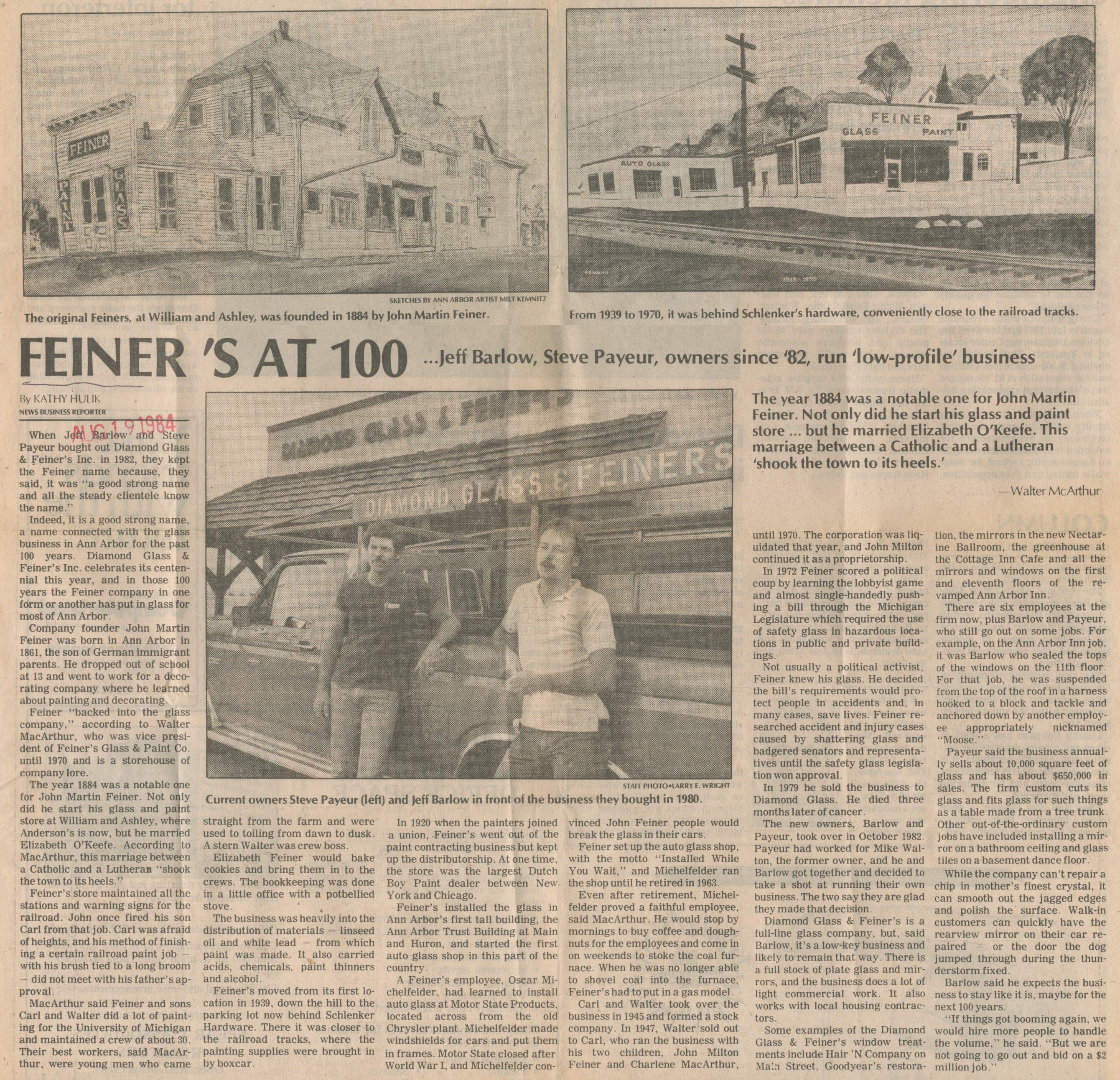

SKETCHES BY ANN ARBOR ARTIST MILT KEMNITZ

The original Feiners, at William and Ashley, was founded in 1884 by John Martin Feiner.

From 1939 to 1970, it was behind Schlenker's hardware, conveniently close to the railroad tracks.

The year 1884 was a notable one for John Martin Feiner. Not only did he start his glass and paint store...but he married Elizabeth O'Keefe. This marriage between a Catholic and a Lutheran 'shook the town to its heels.' ---Walter McArthur

Current owners Steve Payeur (left) and Jeff Barlow in front of the business they bought in 1980.

FEINER'S AT 100...Jeff Barlow, Steve Payeur, owners since '82, run 'low-profile' business

By Kathy Hulik

NEWS BUSINESS REPORTER

When Jeff Barlow and Steve Payeur bought out Diamond Glass & Feiner's Inc. in 1982, they kept the Feiner name because, they said, it was "a good strong name and all the steady clientele know the name."

Indeed, it is a good strong name, a name connected with the glass business in Ann Arbor for the past 100 years. Diamond Glass & Feiner's Inc. celebrates its centennial this year, and in those 100 years the Feiner company in one form or another has put in glass for most of Ann Arbor.

Company founder John Martin Feiner was born in Ann Arbor in 1861, the son of German immigrant parents. He dropped out of school at 13 and went to work for a decorating company where he learned about painting and decorating.

Feiner "backed into the glass company," according to Walter MacArthur, who was Vice President of Feiner's Glass & Paint Co. until 1970 and is a storehouse of company lore.

The year 1884 was a notable one for John Martin Feiner. Not only did he start his glass and paint store at William and Ashley, where Anderson's is now, but he married Elizabeth O'Keefe. According to MacArthur, this marriage between a Catholic and a Lutheran "shook the town to its heels."

Feiner's store maintained all the stations and warning signs for the railroad. John once fired his son Carl from that job. Carl was afraid of heights, and his method of finishing a certain railroad paint job--with his brush tied to a long broom--did not meet with his father's approval.

MacArthur said Feiner and sons Carl and Walter did a lot of painting for the University of Michigan and maintained a crew of about 30. Their best workers, said MacArthur, were young men who came straight from the farm and were used to toiling from dawn to dusk. A stern Walter was crew boss.

Elizabeth Feiner would bake cookies and bring them in to the crews. The bookkeeping was done in a little office with a potbellied stove.

The business was heavily into the distribution of materials--linseed oil and white lead--from which paint was made. It also carried acids, chemicals, paint thinners and alcohol.

Seiners moved from its first location in 1939, down the hill to the parking lot now behind Schlenker Hardware. There it was closer to the railroad tracks, where the painting supplies were brought in by boxcar.

In 1920 when the painters joined a union, Feiner's went out of the paint contracting business but kept up the distributorship. At one time, the store was the largest Dutch Boy Paint dealer between New York and Chicago.

Feiner's installed the glass in Ann Arbor's first tall building, the Ann Arbor Trust Building at Main and Huron, and started the first auto glass shop in this part of the country.

A Feiner's employee, Oscar Michelfelder, had learned to install auto glass at Motor State Products, located across from the old Chrysler plant. Michelfelder made windshields for cars and put them in frames. Motor State closed after World War I, and Michelfelder convinced John Feiner people would break the glass in their cars.

Feiner set up the auto glass shop, with the motto "Installed While You Wait," and Michelfelder ran the shop until he retired in 1963.

Even after retirement, Michelfelder proved a faithful employee, said MacArthur. He would stop by mornings to buy coffee and doughnuts for the employees and come in on weekends to stoke the coal furnace. When he was no longer able to shovel coal into the furnace, Feiner's had to put in a gas model.

Carl and Walter took over the business in 1945 and formed a stock company. In 1947, Walter sold out to Carl, who ran the business with his two children, John Milton Feiner and Charlene MacArthur, until 1970. The corporation was liquidated that year, and John Milton continued it as a proprietorship.

In 1972 Feiner scored a political coup by learning the lobbyist game and almost single-handedly pushing a bill through the Michigan Legislature which required the use of safety glass in hazardous locations in public and private buildings.

Not usually a political activist, Feiner knew his glass. He decided the bill's requirements would protect people in accidents and, in many cases, save lives. Feiner researched accident and injury cases caused by shattering glass and badgered senators and representatives until the safety glass legislation won approval.

In 1979 he sold the business to Diamond Glass. He died three months later of cancer.

The new owners, Barlow and Payeur, took over in October 1982. Payeur had worked for Mike Walton, the former owner, and he and Barlow got together and decided to take a shot at running their own business. The two say they are glad they made that decision.

Diamond Glass & Feiner's is a full-line glass company, but, said Barlow, it's a low-key business and likely to remain that way. There is a full stock of plate glass and mirrors, and the business does a lot of light commercial work. It also works with local housing contractors.

Some examples of the Diamond Glass & Feiner's window treatments include Hair 'N Company on Main Street, Goodyear's restoration, the mirrors in the new Nectarine Ballroom, the greenhouse at the Cottage Inn Cafe and all the mirrors and windows on the first and eleventh floors of the revamped Ann Arbor Inn.

There are six employees at the firm now, plus Barlow and Payeur, who still go out on some jobs. For example, on the Ann Arbor Inn job, it was Barlow who sealed the tops of the windows on the 11th floor. For that job, he was suspended from the top of the roof in a harness hooked to a block and tackle and anchored down by another employee appropriately nicknamed "Moose."

Payeur said the business annually sells about 10,000 square feet of glass and has about $650,000 in sales. The firm custom cuts its glass and fits glass for such things as a table made from a tree trunk. Other out-of-the-ordinary custom jobs have included installing a mirror on a bathroom ceiling and glass tiles on a basement dance floor.

While the company can't repair a chip in mother's finest crystal, it can smooth out the jagged edges and polish the surface. Walk-in customers can quickly have the rearview mirror on their car repaired--or the door the dog jumped through during the thunderstorm fixed.

Barlow said he expects the business to stay like it is, maybe for the next 100 years.

"If things got booming again, we would hire more people to handle the volume," he said. "But we are not going to go out and bid on a $2 million job."

Article

Subjects

Kathy Hulik

Feiner Glass & Paint Co.

Local History

Diamond Glass & Feiner's Inc.

Schlenker Hardware Co.

Ann Arbor Trust Building

Motor State Products

Laws & Legislation

Consumer Protection

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

John Martin Feiner

Jeff Barlow

Steve Payeur

Elizabeth O'Keefe Feiner

Carl M. Feiner

Walter MacArthur

Oscar Michelfelder

Walter J. Feiner

John Milton Feiner

Charlene MacArthur

Mike Walton