A Driving Force At Ford

A driving force at Ford

In its list of top corporate women, Ebony magazine hands a kudo to Ann Arbor’s Willie Hobbs Moore

By RUSSELL GRANTHAM

NEWS STAFF REPORTER

When Willie Hobbs Moore comes down to the lobby of Ford Motor Co.’s Dearborn headquarters from her fifth-floor office, she acts truly embarrassed at the attention being paid to her.

“Come on, Hobbs, that’s not you,” she says. “I really think that it’s been blown out of proportion, you know what I mean?”

What Moore thinks has been blown out of proportion is the fact that Ebony magazine listed her as one of the 100 “Most Promising Black Women in Corporate America” in its January issue. An Ann Arbor resident, she is a senior quality associate for Ford.

According to the article, the 100 who were singled out “are bright, talented women who take their jobs seriously and use their time prudently... On the job they must look great but not trendy or flashy; they must exude confidence without arrogance, and exhibit assertiveness without giving the perception of being too aggressive.”

Moore seems to fit the bill.

Yes, she says, she was the “first female black engineering type” to get a doctorate in physics from the University of Michigan, in 1972. But then she adds, “There are really a lot of neat, good folks out there who don’t get the billing or don’t get the chance to deserve the billing.”

“She has had a very significant impact on the quality methods and engineering technology at Ford and the rest of the auto industry,” says her former boss, Larry Sullivan, who collaborated with Moore and others to introduce Japanese engineering and manufacturing methods at Ford in the 1980s. He is now chairman of the American Supplier Institute, a Dearborn-based training and consulting firm inspired by quality guru William Edwards Deming and spun off by Ford in 1985.

“She deserves a lot more credit than she’ll admit to,” he says. “She would say ‘No, no, I didn’t do all that.’ She really does discount her accomplishments.”

One of her contributions was a technical paper in which she took the concepts of Genichi Taguchi, an award-winning Japanese engineering professor and consultant, and developed them into working design methods “that can be used by the average engineer,” he says. “I’ll tell you, that paper is all over the world.”

Peter Jessup, manager of Ford’s Quality Education and Training Center and Moore’s boss, says he and others at Ford submitted her name to Ebony because “she’s a strong person. She’s committed to making a contribution... and she’s got the talent to back it up.”

For the past two years, he says, she has served as the key person on a program to train “quality liaisons” from the United Auto Workers local unions in Ford plants. It’s a job that requires strong persuasive powers, he says, because “all the technology in the world won’t work” unless auto workers are willing and able to work with it.

Moore was recruited by Ford in 1977 from the University of Michigan’s Physics Department, where she was working as a lecturer and research physicist. A native of Atlantic City, N.J., she had earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from U-M in 1958 and 1961 and had worked in Ann Arbor at firms such as KMS Industries and Datamax Corp. while studying for her doctorate. She started out at Ford as an engineer in its Automotive Assembly Division.

Back then, Moore believes, many of her colleagues assumed Ford hired her not for her qualifications but because the company was filling a minority hiring quota for an affirmative action program. Some, such as her first boss, didn’t care what color she was, she says. She works well with the colleagues she has now, she adds. “I have to say that most of the time it’s all right,” she says. But that hasn’t been and isn’t always the case, she adds.

Sometimes, it’s hard to tell which conflicts are motivated by the rough-and-tumble of daily business and which ones have an undercurrent of racial or gender bias, she explains. “It’s hard, because I think you develop a paranoia. You don’t know what’s honest and what’s prejudiced,” she says.

“Sometimes I think I’m being mistreated and I’m not,” she says. “It could be me. It could be them. They may have had a bad day,” she says.

“Even in the 1990s, a ‘glass ceiling’ does indeed exist, just as it did years ago when black women started pursuing high-powered corporate positions,” states Ebony in its article on the 100 women, asserting that “subtle discrimination” still blocks access to top corporate jobs.

Is there a “glass ceiling” at Ford?

“I can’t really say that,” says Moore, noting that Ford has a woman vice president, Helen Petrauskas, in charge of environmental and safety engineering, and a black vice president, Elliot Hall, in charge of Washington affairs. (Ford has 30 vice presidents and five executive vice presidents, says Katie Blackwell, a spokeswoman for Ford.)

Moore says she and her husband, Sidney L. Moore, who’s a teacher at the U-M’s Neuropsychiatric Institute, tried to teach their two children “not to use your blackness as an excuse not to excel. No excuses. But sometimes when you teach that without balancing it with the unfairness of the real world, we do our children a disservice. It’s real difficult out here for black people.” Their daughter Dorian is in her final year of medical school at the U-M; then-son Christopher is an undergraduate at Michigan State University.

Moore spends her spare time, as she has for more than 20 years, tutoring math and science in Ann Arbor for the children of friends, people in her church, and through her membership in Links Inc., a national community service organization run mostly by black women.

“What you have to do is learn to survive,” she tells minority engineering students at the U-M. “The world is not going to change. It really isn’t,” she says, adding that there will always be prejudiced people. “You’ve got to be prepared to survive in spite of their attitudes.” And, she adds, there’s the first rule of survival: “You’ve got to be excellent.”

NEWS PHOTO • COLLEEN FITZGERALD

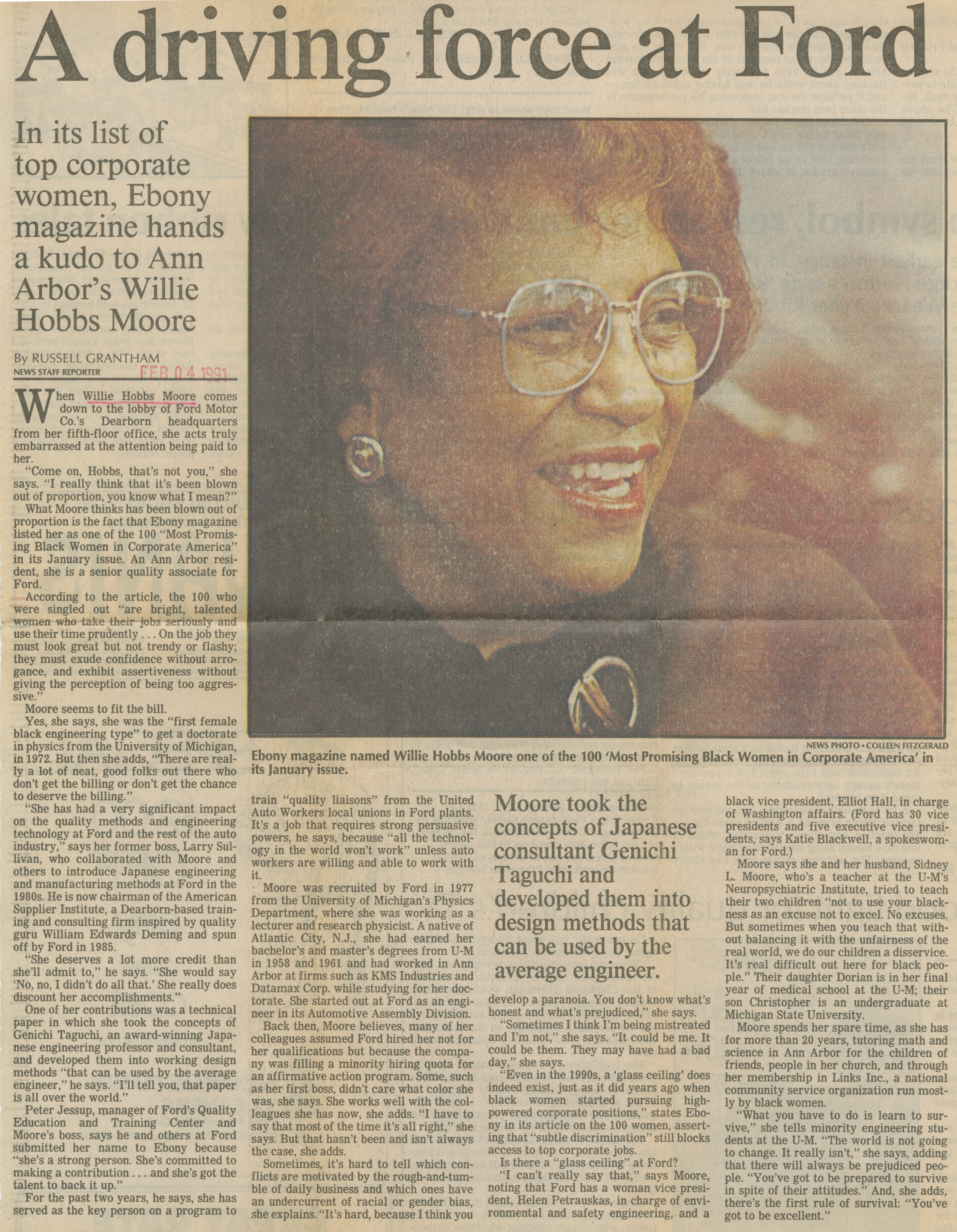

Ebony magazine named Willie Hobbs Moore one of the 100 'Most Promising Black Women in Corporate America' in its January issue.

Moore took the concepts of Japanese consultant Genichi Taguchi and developed them into design methods that can be used by the average engineer.

Article

Subjects

Russell Grantham

Ford Motor Co.

Ebony Magazine

Black American Women

Black Americans

University of Michigan - Alumnus

University of Michigan - Department of Physics

American Supplier Institute

United Auto Workers

KMS Industries

Datamax Corp.

Links Inc

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

Willie Hobbs Moore

Larry Sullivan

William Edwards Deming

Genichi Taguchi

Peter Jessup

Helen Petrauskas

Elliot Hall

Katie Blackwell

Sidney L. Moore

Dorian Moore

Christopher Moore

Colleen Fitzgerald