U Experts Solving Mummy Mystery

The discovery of what has been a missing link in Egypt's royal mummies collection was revealed today by a team of U-M scientists who conducted a "break in" in that country last spring.

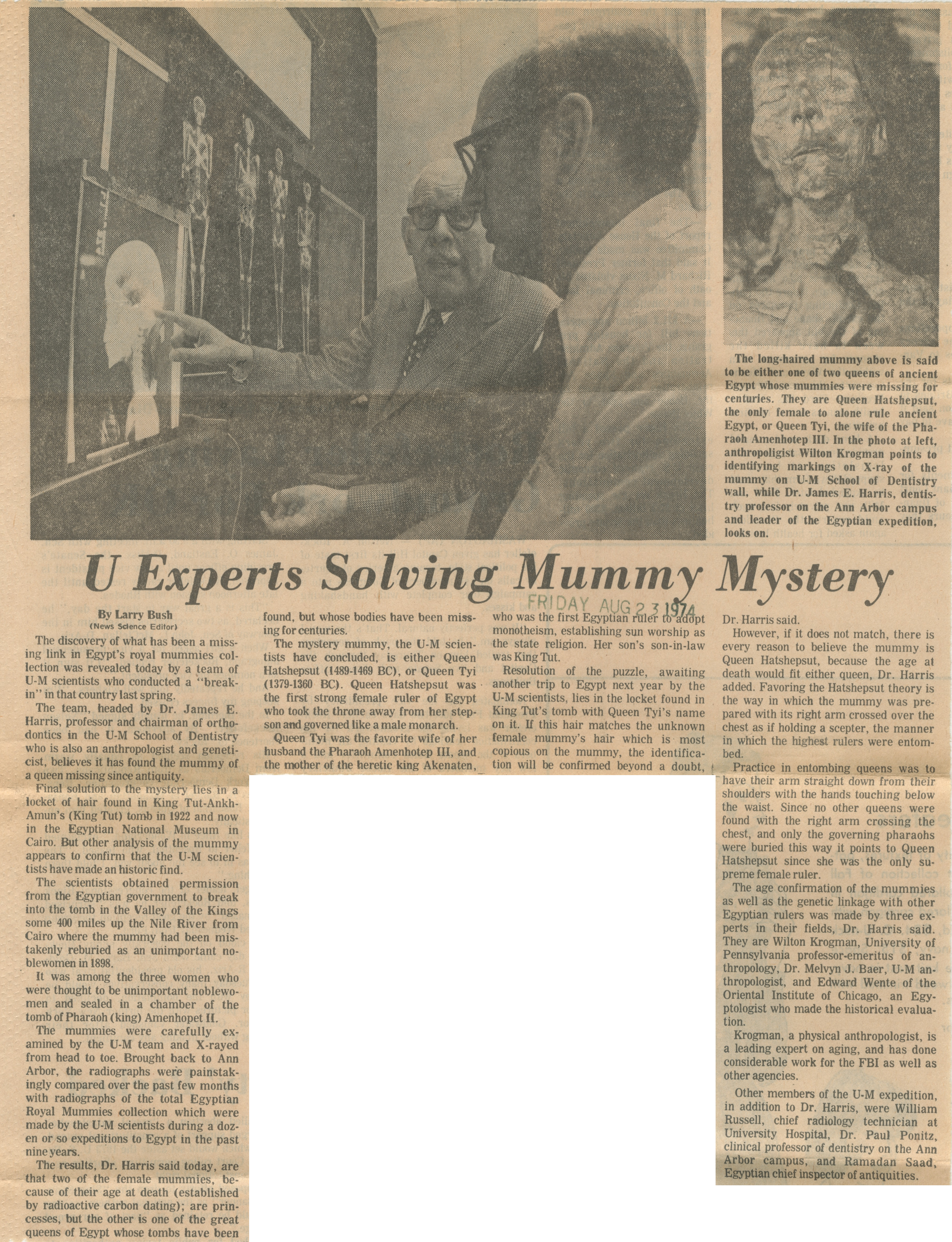

The team, headed by Dr. James E. Harris, professor and chairman of orthodontics in the U-M School of Dentistry who is also an anthropologist and geneticist, believes it has found the mummy of a queen missing since antiquity.

Final solution to the mystery lies in a locket of hair found in King Tut-Ankh-Amun's (King Tut) tomb in 1922 and now in the Egyptian National Museum in Cairo. But other analysis of the mummy appears to confirm that the U-M scientists have made an historic find.

The scientists obtained permission from the Egyptian government to break into the tomb in the Valley of the Kings some 400 miles up the Nile River from Cairo where the mummy had been mistakenly reburied as an unimportant noblewoman in 1898.

It was among the three women who were thought to be unimportant noblewomen and sealed in a chamber of the tomb of Pharaoh (king) Amenhopet II.

The mummies were carefully examined by the U-M team and X-rayed from head to toe. Brought back to Ann Arbor, the radiographs were painstakingly compared over the past few months with radiographs of the total Egyptian Royal Mummies collection which were made by the U-M scientists during a dozen or so expeditions to Egypt in the past nine years.

The results, Dr. Harris said today, are that two of the female mummies, because of their age at death (established by radioactive carbon dating); are princesses, but the other is one of the great queens of Egypt whose tombs have been found, but whose bodies have been missing for centuries.

The mystery mummy, the U-M scientists have concluded, is either Queen Hatshepsut (1489-1469 BC), or Queen Tyi (1379-1360 BC). Queen Hatshepsut was the first strong female ruler of Egypt who took the throne away from her stepson and governed like a male monarch.

Queen Tyi was the favorite wife of her husband the Pharaoh Amenhotep III, and the mother of the heretic king Akenaten, who was the first Egyptian ruler to adopt monotheism, establishing sun worship as the state religion. Her son's son-in-law was King Tut.

Resolution of the puzzle, awaiting another trip to Egypt next year by the U-M scientists, lies in the locket found in King Tut's tomb with Queen Tyi's name on it. If this hair matches the unknown female mummy's hair which is most copious on the mummy, the identification will be confirmed beyond a doubt, Dr. Harris said.

However, if it does not match, there is every reason to believe the mummy is Queen Hatshepsut, because the age at death would fit either queen, Dr. Harris added. Favoring the Hatshepsut theory is the way in which the mummy was prepared with its right arm crossed over the chest as if holding a scepter, the manner in which the highest rulers were entombed.

Practice in entombing queens was to have their arm straight down from their shoulders with the hands touching below the waist. Since no other queens were found with the right arm crossing the chest, and only the governing pharaohs were buried this way it points to Queen Hatshepsut since she was the only supreme female ruler.

The age confirmation of the mummies as well as the genetic linkage with other Egyptian rulers was made by three experts in their fields, Dr. Harris said. They are Wilton Krogman, University of Pennsylvania professor-emeritus of anthropology, Dr. Melvyn J. Baer, U-M anthropologist, and Edward Wente of the Oriental Institute of Chicago, an Egyptologist who made the historical evaluation.

Krogman, a physical anthropologist, is a leading expert on aging, and has done considerable work for the FBI as well as other agencies.

Other members of the U-M expedition, in addition to Dr. Harris, were William Russell, chief radiology technician at University Hospital, Dr. Paul Ponitz, clinical professor of dentistry on the Ann Arbor campus, and Ramadan Saad, Egyptian chief inspector of antiquities.