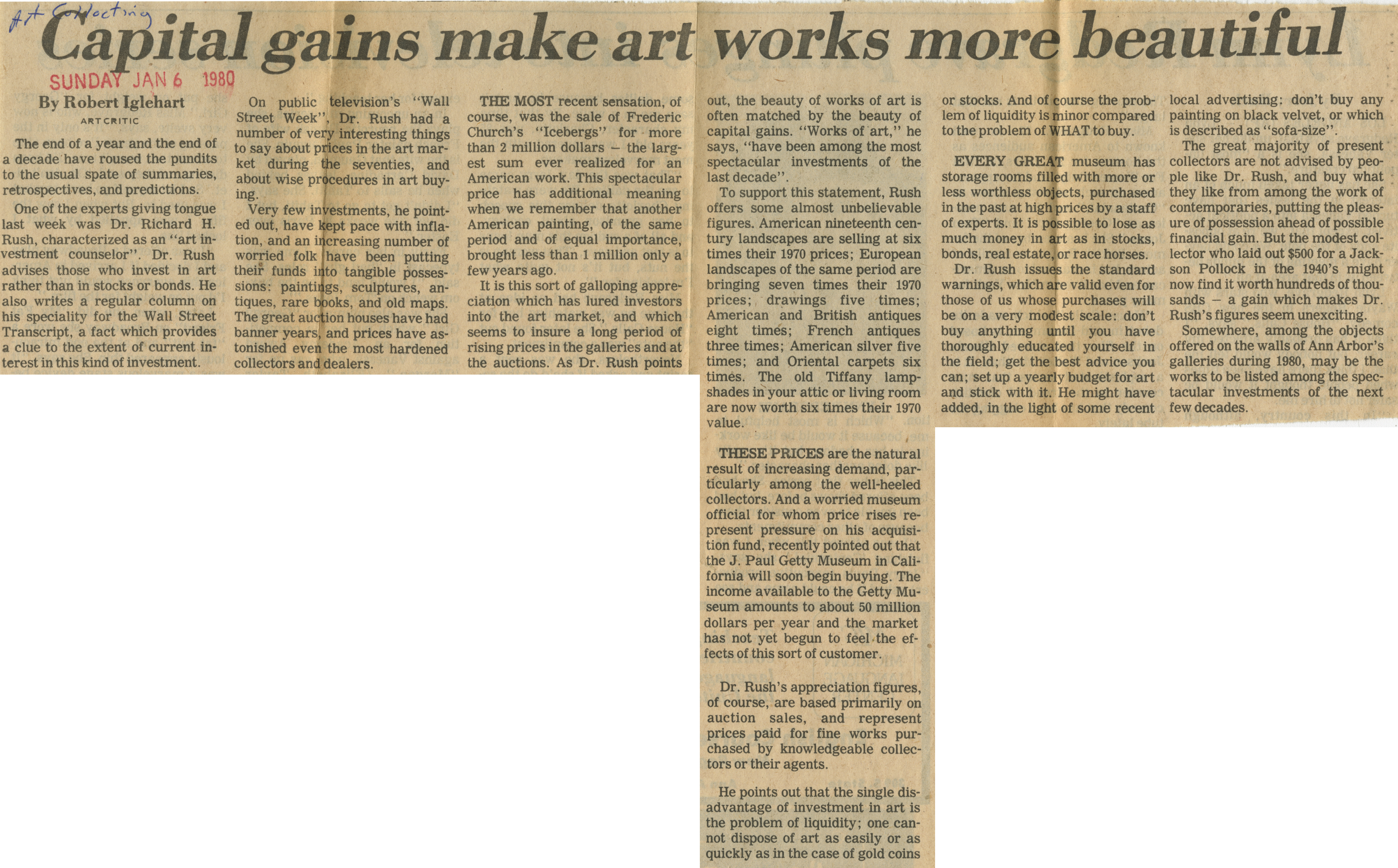

Capital gains make art works more beautiful

Capital gains make art works more beautiful

By Robert Iglehart

ART CRITIC

The end of a year and the end of a decade have roused the pundits to the usual spate of summaries, retrospectives, and predictions.

One of the experts giving tongue last week was Dr. Richard H. Rush, characterized as an "art investment counselor". Dr. Rush advises those who invest in art rather than in stocks or bonds. He also writes a regular column on his specialty for the Wall Street Transcript, a fact which provides a clue to the extent of current interest in this kind of investment.

On public television's "Wall Street Week", Dr. Rush had a number of very interesting things to say about prices in the art market during the seventies, and about wise procedures in art buying.

Very few investments, he pointed out, have kept pace with inflation, and an increasing number of worried folk have been putting their funds into tangible possessions: paintings, sculptures, antiques, rare books, and old maps. The great auction houses have had banner years, and prices have astonished even the most hardened collectors and dealers.

The most recent sensation, of course, was the sale of Frederic Church's "Icebergs" for more than 2 million dollars- the largest sum ever realized for an American work. This spectacular price has additional meaning when we remember that another American painting, of the same, of the same period and of equal importance, brought less than 1 million only a few years ago.

It is this sort of galloping appreciation which has lured investors into the art market, and which seems to insure a long period of rising prices in the galleries and at the auctions. As Dr. Rush points out, the beauty of works of art is often matched by the beauty of capital gains. "Works of art," he says, "have been among the most spectacular investments of the last decade".

To support this statement, Rush offers some almost unbelievable figures. American nineteenth century landscapes are selling at six times their 1970 prices; European landscapes of the same period are bringing seven times their 1970 prices; drawings five times; American and British antiques eight times; French antiques three times; and Oriental carpets six times. The old Tiffany lampshades in your attic or living room are now worth six times their 1970 value.

THESE PRICES are the natural result of increasing demand, particularly among the well-heeled collectors. And a worried museum official for whom price rises represent pressure on his acquisition fund, recently pointed out that the J. Paul Getty Museum in California will soon begin buying. The income available to the Getty Museum amounts to about 50 million dollars per year and the market has not yet begun to feel the effects of this sort of customer.

Dr. Rush's appreciation figures, of course, are based primarily on auction sales, and represent prices paid for fine works purchased by knowledgable collectors or their agents.

He points out that the single disadvantage of investment in art is the problem of liquidity; one cannot dispose of art as easily or as quickly as in the case of gold coins or stocks. And of course the problem of liquidity is minor compared to the problem of WHAT to buy.

EVERY GREAT museum has storage rooms filled with more or less worthless objects, purchased in the past at high prices by a staff of experts. It is possible to lose as much money in art as in stocks, bonds, real estate, or race horses.

Dr. Rush issues the standard warnings, which are valid even for those of us whose purchases will be on a very modest scale: don't buy anything until you have thoroughly educated yourself in the field; get the best advice you can; set up a yearly budget for art and stick with it. He might have added, in the light of some recent local advertising: don't buy any painting on black velvet, or which is described as "sofa-size".

The great majority of present collectors are not advised by people like Dr. Rush, and buy what they like from among the work of contemporaries, putting the pleasure of possession ahead of possible financial gain. But the modest collector who laid out $500 for a Jackson Pollock in the 1940's might now find it worth hundreds of thousands- a gain which makes Dr. Rush's figures seem exciting.

Somewhere, among the objects offered on the walls of Ann Arbor's galleries during 1980, may be the works to be listed among the spectacular investments of the next few decades.