Self-Sufficiency Is Key To Plans For Former University Center

CONNECTION

Cats could be health hazard-G5

Self-sufficiency is key to plans for former University Center

STORY BY RAY SLEEP

PHOTOS BY JACK STUBBS

OF THE NEWS STAFF

Co-op members plan to establish a model "eco-village" in the building, on its grounds and on a wooded site next door, at the edge of the North Campus.

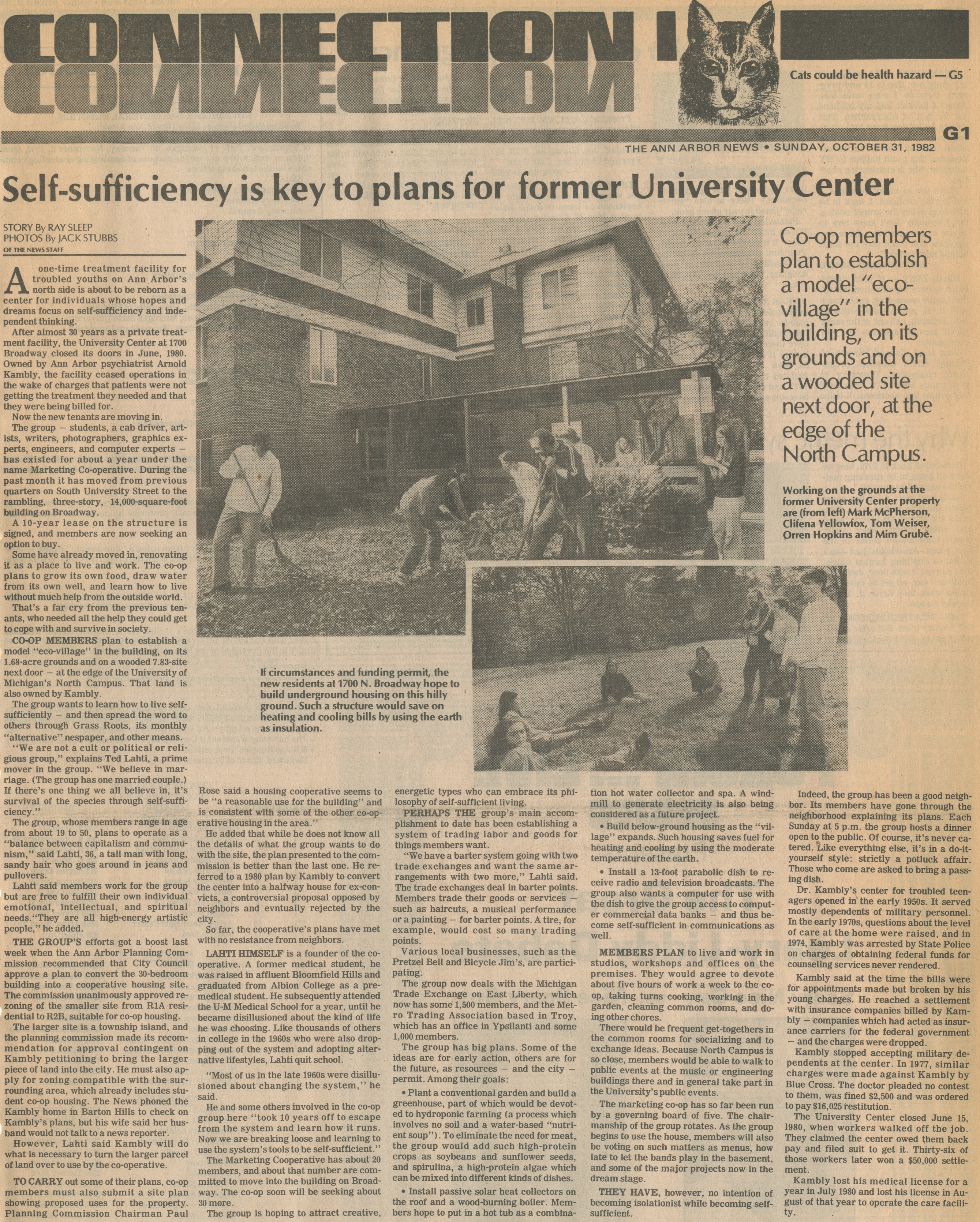

Working on the grounds at the former University Center property are (from left) Mark McPherson, Clifena Yellowfox, Tom Weiser, Orren Hopkins and Mim Grube.

If circumstances and funding permit, the new residents at 1700 N. Broadway hope to build underground housing on this hilly ground. Such a structure would save on heating and cooling bills by using the earth as insulation.

A one-time treatment facility for troubled youths on Ann Arbor's north side is about to be reborn as a center for individuals whose hopes and dreams focus on self-sufficiency and independent thinking.

After almost 30 years as a private treatment facility, the University Center at 1700 Broadway closed its doors in June 1980. Owned by Ann Arbor psychiatrist Arnold Kambly, the facility ceased operations in the wake of charges that patients were not getting the treatment they needed and that they were being billed for.

Now the new tenants are moving in.

The group-students, a cab driver, artists, writers, photographers, graphics experts, engineers, and computer experts-has existed for about a year under the name Marketing Co-operative. During the past month it has moved from previous quarters on South University Street to the rambling, three-story, 14,000-square-foot building on Broadway.

A 10-year lease on the structure is signed, and members are now seeking an option to buy.

Some have already moved in, renovating it as a place to live and work. The co-op plans to grow its own food, draw water from its own well, and learn how to live without much help from the outside world.

That's a far cry from the previous tenants, who needed all the help they could get to cope with and survive in society.

CO-OP MEMBERS plan to establish a model "eco-village" in the building, on its 1.68-acre grounds and on a wooded 7.83-site next door-at the edge of the University of Michigan's North Campus. That land is also owned by Kambly.

The group wants to learn how to live self-sufficiently-and then spread the word to others through Grass Roots, its monthly "alternative" newspaper, and other means.

"We are not a cult or political or religious group," explains Ted Lahti, a prime mover in the group. "We believe in marriage. (The group has one married couple.) If there's one thing we all believe in, it's survival of the species through self-sufficiency."

The group, whose members range in age from about 19 to 50, plans to operate as a "balance between capitalism and communism," said Lahti, 36, a tall man with long, sandy hair who goes around in jeans and pullovers.

Lahti said members work for the group but are free to fulfill their own individual emotional, intellectual, and spiritual needs. "They are all high-energy artistic people," he added.

THE GROUP'S efforts got a boost last week when the Ann Arbor Planning Commission recommended that City Council approve a plan to convert the 30-bedroom building into a cooperative housing site. The commission unanimously approved rezoning of the smaller site from R1A residential to R2B, suitable for co-op housing.

The larger site is a township island, and the planning commission made its recommendation for approval contingent on Kambly petitioning to bring the larger piece of land into the city. He must also apply for zoning compatible with the surrounding area, which already includes student co-op housing. The News phoned the Kambly home in Barton Hills to check on Kambly's plans, but his wife said her husband would not talk to a news reporter.

However, Lahti and Kambly will do what is necessary to turn the larger parcel of land over to use by the co-operative.

TO CARRY out some of their plans, co-op members must also submit a site plan showing proposed uses for the property. Planning Commission Chairman Paul Rose said a housing cooperative seems to be "a reasonable use for the building" and is consistent with some of the other co-operative housing in the area."

He added that while he does not know all the details of what the group wants to do with the site, the plan presented to the commission is better than the last one. He referred to a 1980 plan by Kambly to convert the center into a halfway house for ex-convicts, a controversial proposal opposed by neighbors and eventually rejected by the city.

So far, the cooperative's plans have met with no resistance from neighbors.

LAHTI HIMSELF is founder of the cooperative. A former medical student, he was raised in affluent Bloomfield Hills and graduated from Albion College as a pre-medical student. He subsequently attended the U-M Medical School for a year, until he became disillusioned about the kind of life he was choosing. Like thousands of others in college in the 1960s who were also dropping out of the system and adopting alternative lifestyles, Lahti quit school.

"Most of us in the late 1960s were disillusioned about changing the system," he said.

He and some others involved in the co-op group here "took 10 years off to escape from the system and learn how it runs. Now we are breaking loose and learning to use the system's tools to be self-sufficient."

The Marketing Cooperative has about 20 members, and about that number are committed to move into the building on Broadway. The co-op will be seeking about 30 more.

The group is hoping to attract creative, energetic types who can embrace its philosophy of self-sufficient living.

PERHAPS THE group's main accomplishment to date has been establishing a system of trading labor and goods for things members want.

"We have a barter system going with two trade exchanges and want the same arrangements with two more," Lahti said. The trade exchanges deal in barter points. Members trade their goods or services-such as haircuts, a musical performance or a painting-for barter points. A tire, for example, would cost so many trading points.

Various local businesses, such as the Pretzel Bell and Bicycle Jim's are participating.

The group now deals with the Michigan Trade Exchange on East Liberty, which now has some 1,500 members, and the Metro Trading Association based in Troy, which has an office in Ypsilanti and some 1,000 members.

The group has big plans. Some of the ideas are for early action, others are for the future, as resources-and the city-permit. Among their goals:

-Plant a conventional garden and build a greenhouse, part of which would be devoted to hydroponic farming (a process which involves no soil and a water based "nutrient soup"). To eliminate the need for meat, the group would add such high-protein crops as soybeans and sunflower seeds, and spirulina, a high-protien algae which can be mixed into different kinds of dishes.

-Install passive solar heat collectors on the roof and a wood-burning boiler. Members hope to put in a hot tub as a combination hot water collector and spa. A windmill to generate electricity is also being considered as a future project.

-Build below-ground housing as the "village" expands. Such housing saves fuel for heating and cooling by using the moderate temperature of the earth.

-Install a 13-foot parabolic dish to receive radio and television broadcasts. The group also wants a computer for use with the dish to give the group access to computer commercial data banks-and thus become self-sufficient in communications as well.

MEMBERS PLAN to live and work in studios, workshops and offices on the premises. They would agree to devote about five hours of work a week to the co-op, taking turns cooking, working in the garden cleaning common rooms, and doing other chores.

There would be frequent get-togethers in the common rooms for socializing and to exchange ideas. Because North Campus is so close, members would be able to walk to public events at the music or engineering buildings there and in general take part in the University's public events.

The marketing co-op has so far been run by a governing board of five. The chairmanship of the group rotates. As the group begins to use the house, members will also be voting on such matters as menus, how late to let the bands play in the basement, and some of the major projects now in the dream stage.

THEY HAVE, however, no intention of becoming isolationist while becoming self-sufficient.

Indeed, the group has been a good neighbor. Its members have gone through the neighborhood explaining its plans. Each Sunday at 5 p.m. the group hosts a dinner open to the public. Of course, it's never catered. Like everything else, it's in a do-it-yourself style: strictly a potluck affair. Those who come are asked to bring a passing dish.

Dr. Kambly's center for troubled teenagers opened in the early 1950s. It served mostly dependents of military personnel. In the early 1970s, questions about the level of care at the home were raised, and in 1974, Kambly was arrested by State Police on charges of obtaining federal funds for counseling services never rendered.

Kambly said at the time the bills were for appointments made but broken by his young charges. He reached a settlement with insurance companies billed by Kambly-companies which had acted as insurance carriers for the federal government-and the charges were dropped.

Kambly stopped accepting military dependents at the center. In 1977, similar charges were made against Kambly by Blue Cross. The doctor pleaded no contest to them, was fined $2,500 and was ordered to pay $16,025 restitution.

The University Center closed June 15, 1980, when workers walked off the job. They claimed the center owed them back pay and filed suit to get it. Thirty-six of those workers later won a $50,000 settlement.

Kambly lost his medical license for a year in July 1980 and lost his license in August of that year to operate the care facility.

Article

Subjects

Ray Sleep

University Center

Social Services

Marketing Co-operative

Ann Arbor Planning Commission

Ann Arbor City Council

Zoning

Annexations

Michigan Trade Exchange

Metro Trading Association

Alternative Energy

Energy Conservation

Crime & Criminals

Michigan State Police

Blue Cross of Michigan

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

Arnold Kambly

Ted Lahti

Paul Rose

Jack Stubbs

1700 Broadway