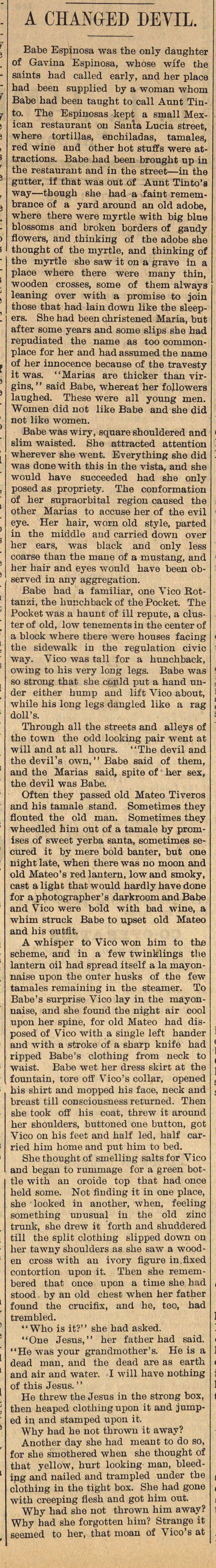

A Changed Devil

Babe Espinosa was the ouly daughter of Gavina Espinosa, whose wife the saints had called early, and her place had been supplied by a woman whom Babe had been taught to cali Aunt Tinto. The Espinosas kept a small Mexican restaurant on Santa Lucia street, where tortillas, enchiladas, tamales, red wine and other hot stuffs were attractions. Babe had been brougbt up in the restaurant and in the street - in the gutter, if that was out of Aunt Tinto'a way - though she had a faint remembrance of a yard around an oíd adobe, where there were niyrtle with big blue blossoms and broken borders of gaudy flowers, and thinking of the adobe she thought of the myrtle, and thinking of the myrtle she saw it on a grave in a place where there were many thin, wooden crosses, some of them always leaning over with a promise to join those that had lain down like the sleepers. She had been christened Maria, but af ter sorae years and some slips she had repudiated the name as too commonplace for her and had assumed the name of her innocence because of the travesty it was. "Marias are thicker than virgins, " said Babe, whereat her followers laughed. These were all young men. Women did not like Babe and she did not like women. Babe was wiry, square shouldered and slim waisted. She attracted attention wherever she went. Everything she did was done with this in the vista, and she would have succeeded had she only posed as propriety. The conformation of her supraorbital región caused the other Marias to accuse her of the evil eye. Her hair, worn old style, parted in the middle and carried down over her ears, was black and only less ooarse than the mane of a mustang, and her hair and eyes wonld have been observed in any aggregation. Babe had a familiar, one Vico Rottanzi, the hucchback of the Pocket. The Pocket was a ha uut of ill repute, a cluster of old, low tenements in the center of a block where there were houses facing the sidewalk in the regulation civic way. Vico was tall for a hunchback, owing to bis very long legs. Babe was so strong that she conld put a hand uuder either hump and lift Vico about, while his long legs dangled like a rag doll's. Through all the streets and alleys of the town the odd looking pair went at will and at all hours. "The devil and the devil's own, " Babe said of thein, and the Marías said, spite of her sex, the devil was Babe. Often they passed old Mateo Tiveros and his tamale stand. Sometimos they flouted the old man. Sometimes they wheedled hiru out of a tamale by promises of sweet yerba santa, sometimes cured it by mere bold banter, but one night late, when there was no moon and old Mateo's redlantern, lowand smoky, cast alight thatwould hardly have done for a photographer's darkroom and Babe and Vico were bold with bad wine, a whim strnck Babe to upset old Mateo and his outfit. A whisper to Vico won him to the scheme, and in a few twinklings the lantern oil had spread itself a la niayonnaise upon the outer husks of the few tamales remaining in the steamer. To Babe's surprise Vico lay in the inayonnaise, and she found the night air cool upon her spine, for old Mateo had disposed of Vico with a single left hander and with a stroke of a sharp knife had ripped Babe's clothing from neck to waist. Babe wet her dress skirt at the fountain, tore off Vico's collar, opened his shirt and mopped his face, neck and breast till consciousness returned. Then she took off his coat, threw it around her shoulders, buttoned one button, got Vico on his feet and half led, half carried him home and put him to bed. She thought of smelling salts for Vico and began to rummage for a green bottle with an oroide top that had once held some. Not fiuding it in one place, she looked in another, when, f eeliug something unusual in the old zinc trunk, she drew it forth and shuddered till the split clothing slipped down on her tawny shoulders as she saw a wooden cross with an ivory figure in.fixed contortion upon it. Then she reinembered that once upon a time she had stood by an old chest when her father found the crucifix, and he, too, had trena bied. "Who is it?" she had asked. "One Jesus, " her father had said. "He was your grandmother's. He is a dead man, and the dead are as eartli and air and water. I will have nothing of this Jesus. ' ' He threw the Jesus in the strong box, then heaped clothiugupon it and jurnped in and stamped upon it. Why had he not throwu it away? Another day she had meant to do so, for she smothered when she thought of that yellow, hurt looking man, Meeding and nailed and trampled under the clothing in the tight box. She had gone with creeping flesh and got him out. Why had she not thrown him away? Why had she forgotten him? Strange it seenied to her, that moan of Vico's at

Article

Subjects

Ann Arbor Argus

Old News