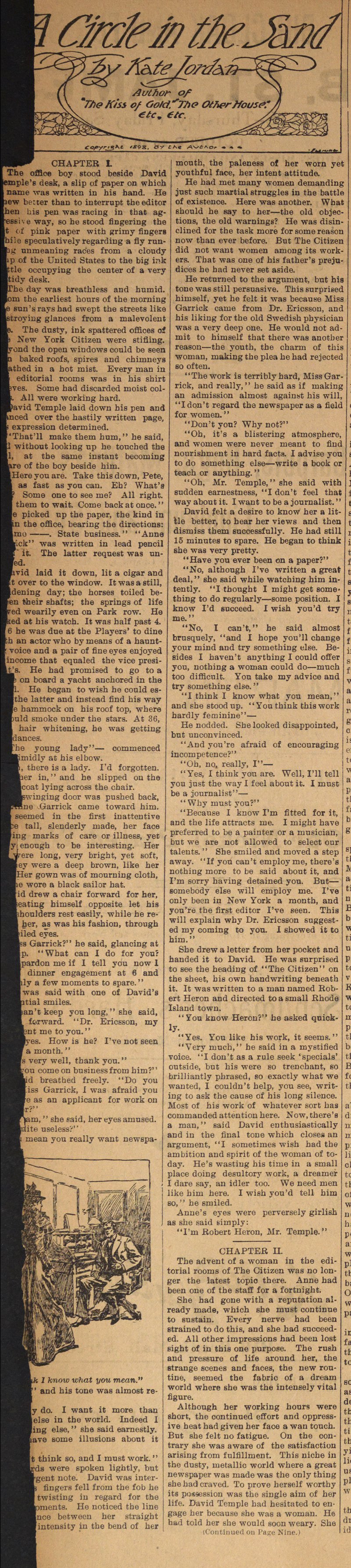

A Circle In The Sand

By Kate Jordan

Author of "A Kiss of Gold," "The Other House," etc. etc.

CHAPTER 1.

The office boy stood beside David Temple's desk, a slip of paper on which a name written in his hand. He knew better than to interrupt the editor when his pen was racing in that aggressive way, so he stood fingering the bit of pink paper with grimy fingers while speculatively regarding a fly running unmeaning races from a cloudy map of the United States to the big ink well occupying the center of a very tidy desk.

The day was breathless and humid. From the earliest hours of the morning the sun's rays had swept the streets like destroying glances from a malevolent (eye). The dusty, ink spattered offices at the New York "Citizen" were stifling. Beyond the open windows could be seen baked roofs, spires and chimneys bathed in a hot mist. Every man in the editorial rooms was in his shirt sleeves. Some had discarded moist collars. All were working hard.

David Temple laid down his pen and glanced over the hastily written page, his expression determined.

"That'll make them hum," he said, without looking up he touched the (bell), at the same instant becoming aware of the boy beside him.

"Here you are. Take this down, Pete, as fast as you can. Eh? What's this? Some one to see me? All right. TelI them to wait. Come back at once."

He picked up the paper, the kind in the office, bearing the directions: "Name______. State business." "Anne (Garrick)" was written in lead pencil on it The latter request was (unheeded).

David laid it down, lit a cigar and went over to the window. It was a still, (maddening) day; the horses toiled beneath their shafts; the springs of life moved wearily even on Park row. He looked at his watch. It was half past 4. At 6 he was due at the Players' to dine with an actor who by means of a haunting voice and a pair of fine eyes enjoyed income that equaled the vice president's. He had promised to go to a (dance) on board a yacht anchored in the (Sound). He began to wish he could escape the latter and instead find his way to the hammock on his roof top, where he could smoke under the stars. At 36, with hair whitening, he was getting too old for dances.

"The young lady" commenced (Pete) timidly at his elbow.

("Oh,), there is a lady! I'd forgotten. (Show her in" and he slipped on the (alpaca) coat lying across the chair.

The swinging door was pushed back, and Anne Garrick carne toward him. (She) seemed in the first inattentive (glance) tall, slenderly made, her face (showing) marks of care or illness, yet (yet pretty) enough to be interesting. Her (eyes) were long, very bright, yet soft, (and) they were a deep brown, like her (hair). Her gown was of mourning cloth, and she wore a black sailor hat.

David drew a chair forward for her, then seating himself opposite let his shoulders rest easily, while be regarded her, as was his fashion, through (half-) veiled eyes

"Miss Garrick?" he said, glancing at (the slip), what can I do for you? (You'll) pardon me if I tell you (at once) that I have a dinner engagement at 6 and have only a few moments to spare."

(This) was said with one of David's (confiden)tial smiles.

("I) shan't keep you long," she said, (leaning) forward. "Dr. Ericsson, my (uncle) sent me to you."

("Oh yes,) how is he? I've not seen (him in) a month."

"He very well, thank you."

("So) you come on business from him?" And (David) breathed freely. "Do you (know) Miss Garrick, I was afraid you (were here) as an applicant for work on (the paper)?"

("So I am,)" she said, her eyes amused. ("Is it quite) useless?"

("You) mean you really want "newspaper work?" and his tone was almost (reproachful.)

("I) really do. I want it more than (anything) else in the world. Indeed I (want nothing else," she said earnestly.

("You) have some illusions about it, (perhaps?")

“You have some illusions about it, perhaps?” “I don't think so, and I must work."

The words were spoken lightly, but with an urgent note. David was interested. His fingers fell from the fob he had been twisting in regard for the passing moments. He noticed the line of impatience between her straight brows, the intensity in the bend of her mouth, the paleness of her worn yet youthful face, her intent attitude.

He had met many women demanding just such martial struggles in the battle of existence. Here was another. What should he say to her - the old objections, the old warnings? He was disinclined for the task more for some reason now than ever before. But the "Citizen" did not want women among its workers. That was one of his father's prejudices which he had never set aside.

He returned to the argument, but his tone was still persuasive. This surprised himself, yet he felt it was because Miss Garrick came from Dr. Ericsson, and his liking for the old Swedish physician was a very deep one. He would not admit to himself that there was another reason — the youth, the charm, of this woman making the plea he had rejected so often.

“The work is terribly hard, Miss Garrick, and really," he said, as if making an admission almost against his will, “I don't regard the newspaper as a field for women."

"Don't you? Why not?"

"Oh, it's a blistering atmosphere, and women were never meant to find nourishment in hard facts. I advise you to do something else - write a book, or teach, or anything."

“Oh, Mr. Temple," she said with sudden earnestness," I don't feel that way about it! I want to be a journalist."

David felt a desire to know her a little better to hear her views and then dismiss them successfully. He had still fifteen minutes to spare. He began to think she was very pretty.

"Have you ever been on a paper ?"

"No, although I've written a great deal," she said, while watching him intently. "I thought I might get something to do regularly - some position. I know I'd succeed. I wish you'd try. I wish you'd try me."

"No - I can't," he said, almost brusquely, and I hope you'll change your mind and try something else. Besides, I haven't anything I could offer you, nothing a woman could do - much too difficult. You take my advice and try something else."

"I think I know what you mean" -- and she stood up. “You think this work hardly feminine" -

He nodded. She looked disappointed, but unconvinced.

"And you're afraid of encouraging incompetence."

"Oh, no, really, I"

“Yes, I think you are. Well, I'll tell you just the way I feel about it. I must be a journalist"

"Why must you?"

"Because I know I'm fitted for it, and the life attracts me. I might have preferred to be a painter or a musician, but we are not allowed to select our talents." She smiled and moved a step away. "If you can't employ me there's nothing more to be said about it, and I'm sorry for having detained you. But--somebody else will employ me. I've only been in New York a month, and you're the first editor I've seen. This will explain why Dr. Ericsson suggested my coming to you. I showed it to him."

She drew a letter from her pocket and handed it to David. He was surprised to see the heading of the "Citizen" on the sheet, his own handwriting beneath it. It was written to a man named Robert Heron, and directed to a small Rhode Island town.

"You know Heron?” he asked quickly.

“Yes. You like his work, it seems."

*Very much," he said, in a mystified voice. "I don't as a rule seeks specials outside, but his were so trenchant, so brilliantly phrased, so exactly what we wanted, I couldn't help, you see, writing to ask the cause of his long silence. Most of his work, of whatever sort, has commanded attention here.

Now, there's a man," said David enthusiastically and in the final tone which closes an argument,"I sometimes wish had the ambition and spirit of the woman of to-day. He's wasting his time in a small place doing desultory work; a dreamer, I dare say an idler too. We need men like him here. I wish you'd tell him so," he smiled.

Anne's eyes were perversely girlish as she said simply:

"I'm Robert Heron, Mr. Temple."

Chapter II

THE advent of a woman in the editorial rooms of the Citizen" was no longer the latest topic there. Anne had been one of the staff for a fortnight.

She had come with a reputation already made, which she must continue to sustain. Every nerve had been strained to do this, and she had succeeded. All other impressions had been lost sight of in this one purpose. The rush and pressure of life around her, the strange scenes and faces, the new routine, seemed the fabric of a dreamworld where she was the intensely vital figure.

Although her working hours were short, the continued effort and oppressive heat had given her face a wan touch. But she felt no fatigue. On the contrary she was aware of the satisfaction arising from fulfilment. This niche in the dusty, metallic world where a great newspaper was made was the only thing she had craved. To prove herself worthy of its possession was the single aim of her life. David Temple had hesitated to engage her because she was a woman. He had told her she would soon weary. She must prove his prophecy false. This was the impetus that made her bold. The result was gratifying.

Matters of social and moral importance started out vividly during the terrible summer weather. The handling of some of these was assigned to Anne. It would seem that David Temple had decided to take her cruelly at her word and treat her as a man, or as if he had wished to force an evidence of affright or weakness from her. He was mistaken. Anne was a soldier's daughter. Best of all, she was confident of her right to be there. Robert Heron had never done better work than came from her pen during that fortnight.

When she had defended her position and won, there came a lull, and without seeming to watch she absorbed a knowledge of the people around her and noticed what events and colorings go to make up existence in a newspaper office.

There was the sentimental reporter, who furtively read and re-read feminine looking letters and sighed over stock reports; the silent man with the scarred face, who smoked strong cigars; the society editor, whose smile was as well oiled as his russet boots; the baby-faced reporter, who betted on everything and "matched" on the smallest provocation; the fretful critic with the perpetual cold in the head, who whose smile was as well oiled as his russet boots; the baby-faced reporter, who betted on everything and "matched" on the smallest provocation; the fretful critic with the perpetual cold in the head, who banged the door as if to insinuate his exit was final, and who always returned in a rush for something forgotten; the artist lounging with an exalted look to his feet, who drew inspiration from Egyptian cigarettes; Pete, the office boy, with terrible worldly knowledge in his pale eyes and the savoir faire of a veteran clubman in his manner, who grew confidential with her and tried to interest her in the intricacies of baseball; and David Temple, the editor-in-chief, who, unlike many of his compeers, worked hard, bringing with him an assurance of well-bred ease and a capability for exertion and endurance.

Her surroundings were so strange that Anne often wondered if it were indeed she who was there, the lonely girl who in the well-stocked library of a silent country house had written most of the historical and descriptive "specials" which had commanded attention.

While the clatter of the presses and the unaccustomed tread of life were in her ears she would close her eyes and summon a vision of a different scene and time: A hollow at the foot of a hill where a great pool lay, and willow branches like green lengths of dishevelled hair trailed in the water; a girl - herself, the Anne Garrick who was dead never to rise again-lying at full length under the trees, her cheek upon an open book, the fragrance of a lost land around her, the whir of unseen wings, the fireflies in the blackness under the cedars or flashing like uneasy eyes from the confusion of lush grass, the sound of water pushing its way through twisted weeds with a coquettish whimper like silk rubbed on silk.

Some snatch of a street song, the exciting news of the last murder, or the clangor of Trinity's bell would frighten these imaginings, and despite her pagan love of nature she would return to work, happy that the last two years of solitude and reverie were over.

David talked to her very little and never about anything save work. She watched him and found him curiously interesting. Other men were more or less of a familiar type, but David Temple was individual. A nascent force marked his lightest action. To be near him was like coming within the radius of a powerful electric current.

She had always liked clean-shaved men. They seemed a degree farther from the idea of the ancestral monkey than their bewhiskered brothers. David was clean-shaved, spare of flesh, strongly built. There was unity in his simple name, stern face, searching gray eyes, and the practical surroundings in which he worked. Back of his desk the bound volumes of the "Citizen" for a generation were sombrely heaped. Electric wires and buildings of granite were visible beyond the window near which he sat. The man and his mission were melodic.

Anne was slowly drawing on her gloves one evening when the reporter with the scarred face laid down his cigar and asked a question of nobody in particular.

"Any of you fellows know where Donald Sefain has hidden himself this time?"

The name attracted her, and she found herself waiting for the reply.

“Oh, Lord, it's too warm to think of Sefain's vagaries! He's probably trying tenement-house life again with some of his slum friends while a penny remains. When he's broke, he'll come back and work for another spurt," the society editor replied with fine unconcern.

"Fool! Flinging himself away! He won't last long."

"D'you know what I'd do if I were in Temple's place and had such a precious bundle of shiftlessness, unconcern and surliness for a so called brother" -

"H'm ! There isn't much doubt about what you'd do."

"Kick him out." And the society editor fingered his imperial tenderly.

"I think he hates Temple more every day, " raid Jack Braidley, the reporter who -"matched. " "He's an idea he's one too many in the world, I fancy. "

The words were hardly spoken when the door opened and a man came in. From the hush greeting his entrance Anne knew it was Donald Sefain. She looked at him attentively. There were unmistakable marks of vagabondism about him - his dusty clothes, churlish manner, long, untidy hair. He was of moderate height and slender build, he carried his shoulders poorly and his eyes were sunken. But for all this his dark, foreign face, sneering, secretive, defiant, was startlingly handsome as he stood in the red, wash tones of the sunset pouring through the dusty Windows. He looked at Anne with some surprise In his glance, his expression questioning; then he became indifferent, nodded curtly to the men, and sat down at a corner desk. From his attitude one would have supposed he was sketching or writing. As she passed him to the door she saw his fingers were motionless, his wide open eyes introspective. While the room contained a dozen men it was evident Donald Sefain would be left alone with his musings. He had withdrawn from the others as if from habit. Even before she had passed into the hall they seemed to have forgotten his existence.

CHAPTER III

Three miles lay between the offices of the "Citizen" and the trio of rooms Anne had rented and furnished during the six weeks of her residence in New York. They were in a low, red brick house divided from the street by a patch of grass and iron palings. The neighborhood had Washington square for its nucleus, the only part of the money making town preserving the mossy tone of Knickerbocker days, where occasional low doorsteps and spindle legged banisters keep the costumes and manners of the century's infancy clear in the memory. Anne loved the queer street, the venerable church opposite, with its unfashionable parishioners and sweet tongued bell, the amethyst light stealing across the landscape of roofs, the fret of trains flashing past in aerial passage not far off and leaving a plume of vapor behind, the passing of many people along the pavements reaching into smoky perspective.

These impressions were a ripening contact, helping to wake her to newer perceptions of life, making her realize that she stood unsupported in a crowded, struggling place.

She had the exhilarating sensations of a daring and capable swimmer who plunges into deep water where only his own skill can keep him afloat.

Her eyes were shining, her color high, as she hurried up the narrow stairway and entered the sitting room. An old man was standing by one of the Windows and turned expectantly as she came in. It was Dr. Ericsson. He looked at her with cool, friendly scrutiny.

"I've been waiting for you again. There's something witching about you, Anne," he said helplessly. "You've quite spoiled me for solitude. Every dinner I have away from you is like sawdust. "

Anne laid her arm lightly around his shoulder. She was a little the taller. There was something charmingly audacious in her young face and protecting attitude contrasted with his gray hair and sixty odd years. She had the impetuosity and assurance of a fresh runner who fears nothing on the long, mysterious race just begun. He had the half defeated expression of one approaching with lagging steps the end and who thinks little even of the winning of that race which nevertheless must be run in one fashion or another.

"I never knew a man so eager for compliments, " she said, her lips curling in playful scorn. "Shall I fib and say every meal is lonely without you? Not a bit of it. I come home so hungry, uncle, dear, and the man at the corner sends in such good chops. I put on a blouse and dream over my coffee, while Nora in the kitchen sings Irish melodies in an adorable voice and with a dreamlike brogue. "

She laid her finger under his chin and looked into his eyes.

"But when you do come, you dear, cynical creature, I shelve dreams gladly and don't care a pin for Nora's songs. Satisfied?"

She hurried away to change her gown, and Dr. Ericsson was left alone in the dusk. He listened in a dreamy way to the maid crossing and recrossing the rug covered floor, his arms hung by his sides, his eyes were fastened on a trail of smoke diminishing in the sunset.

Thirty years before, then a young Swede newly arrived in America for a bout with fortune, he had married the sister of Anne's mother. They had settled in New York, and by degrees he became successful and rich. His wife was a beauty, his children's future bright, and life went well. But trouble came. His children, with the exception of Olga, the youngest, died during schooldays, his fortune entrusted to false friends went to help their speculations and was lost. Now, in old age, he was a physician of reputation, but poor, possessing a fashionably inclined wife, whose weekly letters from Paris, where she had elected to live when 0lga's schooldays in Switzerland were over, were wearying longings for the vanished wealth. His daughter was almost a stranger to him. She had gone away a child, she was now a woman of 20; what sort of a woman, evolved by her mother's worldliness and a false system of education, he hesitated to consider. His life was spent in the depleted family mansion on Waverly place with one old servant, amid furniture masked in gray holland and portraits of his lost children blinking through gauze sheetings. Only his patients and friends had prevented him from becoming like the piano in the corner, which had almost forgotten how to víbrate. But he knew what a home might be since Anne came to New York. He was deeply fond of her, wholly in sympathy with her. His gaze wandered to a shadowy pastel on the wall before him where her deep eyes were touched by the sunset's fire. It seemed to tell him much. Hers had been a stern, starved girlhood up to the present year. After college days and between the ages of 20 and 23 she had been chained to the bedside of an invalid father, her life a strain when it was not stagnation, unused energy fretting her heart, what should have been the sunniest period of her life drifting by in shadow. When her father died, she had found herself wholly orphaned and free to plan her future according to her tastes. She had a small income, a thorough education and the talent of being able to write with splendor and force of whatever she felt deeply. The controlled yearnings for freedom had grown into one desire, and she had gratifled it. The old home was rented, and like a young David entering the camp of the Philistines she had come to New York. Three things she had determined on - to live alone, work, fill her days with impressions of life, fling away books and study men and women.

When the maid appeared with candles, Anne followed her, a bowl of roses in her hands. The newspaper woman in severe, collared gown was gone, and in her place was an exquisite creature akin to the flowers and the starry lights. Her shoulders and arms gleamed through a gauzy black bodice. A modish knot showed the fine abundance of her hair. One rose was fastened at her bosom, where it flamed in splendid warmth.

Dr. Ericsson looked at her critically. She was more than pretty; she was imperfectly lovely, or, rather, beautiful without fulfilling conventional canons. During quiet moments her face was serene and alluring, the dark hair upon the pale brow like banded velvet, the liquid brown eyes poeticaïly thoughtful, the mouth appealing. Softness, strength and color were all there. But in action and expression lay her strongest charm. When the lips smiled, the eyes lightened and the small, delicate hands, as restless as a Frenchwoman's, emphasized her words, Anne was irresistible.

"I am going to give you a summer dinner, " she said, her fingers lingering among the roses.

"Nothing but roses?"

"You'd be near Nirvana if that could satisfy you. Nora, bring the soup," she added in a purposely practical tone as she seated herself.

They were like children together. Anne listened attentively as she led the old man on to philosophize of life as he saw it. She told him of her newspaper work, its newness, its delight; of the novel she had commenced and how sometimes she rose at dead of night to make a note of an idea or a phrase; of all her faiths, dreams and prejudices. To him she was piteously youthful. To her he was old, wise and weary. He had settled all with destiny. She was buckling on her armor. It seemed that the heart he had lost throbbed in her bosom. He longed that the impossible might be made possible and she might keep it forever so, valiant, free, happy.

"I suppose you know David Temple very well by this time?" he asked.

"You'd be surprised if you knew how seldom he has spoken to me," she said, resting familiarly on her elbow. "He sometimes seems a marvelously constructed machine instead of a man. He works so hard. He seems able to attend to 20 things at once."

"Yes; to lead is in his blood "

"That's it," she nodded. "If he'd been born in a forest in tribal days, they'd have made him chief. Or can't you fancy him a pirate, or a stupendous criminal with a horde of cringing followers, or a cardinal with an eye to pierce a conscience and subjugate a king, or a general like Napoleon, gazing indifferently over the fields of the dead? Do you know, " she said in an awed, childish way, I like him."

"All women like him," snapped Dr. Ericsson.

"Do they?"

"It's a feminine instinct which nothing can kill to like the man who dominates you - and who can do without you?"

"Well, go on," she said, leaning closer.

"Women and their affairs, '" said Dr. Ericsson, lighting a cigar, "engage David Temple's thoughts very little. He is not intolerant, he is simply indifferent, although most masculine in the gentleness coming from a consciousness of his own strength. It seems to me as if a woman could never fill his many sided life. There are men born with the love of woman in their being, and it grows with their growth. To possess it too strenuously weakens a character and often perverts what should be a reverence into a taste. To possess it with a separateness from the other interests of life suggests the lack of some vital and spiritual fiber. I've felt this with David. If he ever marries, it will be because his intellect suggests it as wise or because his physical nature is enslaved. The two will scarcely blend."

"Yes, he suggests all you say. By the way, who is Donald Sefain - his stepbrother?"

"Oh, have you seen him?"

"This afternoon. His face haunted me all the way home."

"I see you have Vaudel's 'Desert Monk' on your shelf. You've read it. The pictures are Donald Sefain's. Fine, aren't they? I half believe he made them just to show what he could do, and then from 'cussedness' flung down his pen. He's done no serious work since "

"Do tell me about him," and Anne, leaving the table, wheeled a low arm chair to Dr. Ericsson 's knee.

"It's a bit of a story. Can you reach me a match? Thank you, my dear."

"This is very cozy." He sat back and half closed his eyes. "When David Temple was about 15, his father, as hard and stern a man as ever lived, married a Frenchwoman, a widow with a boy of 6. Some people know and a great many suspect there never was a Mr. Sefain, and the boy Donald was as surely John Temple's son as David, for whom he'd have cut out his eyes; he loved him so. Well, Mrs. Sefain was a beautiful woman, an adventuress with the manners of a duchess. I never saw her in a brocade dress without thinking how well she'd look on one of those little pompadour fans, all covered with roses and things. Donald is the picture of her. I think his eyes and smile - the latter too rare, God help him - would glorify a plain face into beauty. After five years of the most absolutely perfect marital misery Donald's mother died, and he was left in old John Temple's care. It was a hard fate."

"Why? He didn't like him?"

"Like him? He hated him as only an intolerant, conscientious man can hate. Donald was a constant reproach to him and a reminder of his married unhappiness. He never let David be friends with him, never. You see, Donald hadn't a fair chance He was a lonely little soul."

"Why didn't he set his teeth and make something of himself?" said Anne with the defiance of a champion.

"Ah, that's what he should have done exactly! But he didn't. Instead, at 20, after leaving John Temple's house he went from bad to worse. His face today bears scars of the odds against him. He's a failure. I tried to get near him, but he wouldn't let me be his friend. It is one of his perversities to affect the poor and mingle with the unfortunate. Anything prosperous inspires a morbid dislike in him; all that's deformed, shunned ; all that lies in shadow finds favor in his sight. He's a strange and silent creature, drinking feverishly, cultivating his worst instincts, finding an unreasonable satisfaction in offering himself as a sacrifice to the discontent instilled into him through the circumstances of his life."

"I don't understand why he's on The Citizen with David Temple."

"Oh, he simply does work for that as well as a few other papers! He's brimful of talent. David employs him as he would a stranger and pays him for what work he turns in. He's seldom in the office.''

The clock struck 9, and Dr. Ericsson started up.

"Good heavens! And a sick man not a mile away is waiting for me !"

He got into his coat, kissed her and hurried away. She carried the bowl of roses from the table to the mantel and stood for a moment with her hands upon them, a look of disquietude in her eyes She was thinking of Donald Sefain.

CHAPTER IV.

A fresh, bright afternoon, a vagrant from spring coming between stretches of torrid heat.

The stone hall leading from the editorial rooms to the stairs was deserted as David Temple stepped from his office. He could hear voices and laughter through half opened doors, the din from the streets and shrieking from factory whistles sounding at that height like the growing howl of a mob. When he turned the corner, he saw Anne Garrick, her hand upon the brass scrollwork around the elevator. She looked tired and very young.

A protest leaped into David's heart. He had sometimes experienced the same feeling for a city child contentedly threading beads in the gutter, a wish to transplant it to something more happy, to a meadow where breeze, sunlight and leafage were a symphony. At the thought a grim smile twitched his lips. Miss Garrick was weary of peace and loved the treadmill work in the noisy world. She had told him so.

"Have you rung?" he said, reaching her side.

"Yes, but there's some delay below," said Anne, peering down.

"I'll emphasize the fact that the editor and one of the best writers on The Citizen are waiting." A flash of humor carne into his eyes and he kept his finger upon the bell until its vibrations awoke echoes in the shaft. It was no use, and David looked distressed.

"We'll have to take to the stairs. Give me your parasol and let's make the best of it. You can rest by the way. "

They went side by side down the seemingly never ending iron stairway.

"Are you tired?" he asked when the second landing had been reached."Wait a minute." David took off his hat and stood facing her.

They were in deep shadow, the sounds of life above, below, seeming to skim around without touching their isolation.

"Miss Garrick, I've wanted to say something to you for several days," he said, smiling. "I want to take back what I said about women being unfit for newspaper work. You have done splendidly and against great odds."

"Oh, do you think so?" And the color came into Anne's cheeks. "I did find the work hard, and it's been so hot." Her glance became a little challenging. "And do you think a woman may be still feminine even if she is not an exotic?"

"Oh, I like the exotic woman!" said David as they went on. "I like a woman sublimely useless, providing she's a lot of other things. You have proved

(Continued on Tenth Page.)

(Continued from Page Nine.)

your right to the career you've chosen, but you're one of a paralyzing minority. Why don't you acknowledge it?"

His tone was intentionally provoking, and Anne laughed, her glance a negative.

As they stepped from the shadow into the light of the lower hall the glare through the arcway of the door dazzled them.

"It's a lovely day," said David. "The atmosphere is amazingly clear." They paused for a moment on the doorstep and looked at the picture the the city. "Every detail, " he added, "shows with the accuracy of a photograph - the blue in the shirts of those laborers, the brown of the trench, the violet green of that bit of grass, the flags in the blue air. Are you going to walk?" he asked abruptly.

"Yes; there's such a good breeze. "

"If you've no objection, I'll walk with you."

A pulse of exultation quickened in Anne's heart as they went up the swarming street, David adapting his steps to hers.

"Tell me," he said curiously, "what Dr. Ericsson thinks of your independent spirit."

"He takes it entirely for granted."

"I am behind the times, I suppose," he said, with a short laugh. "Well, I can't help it. I don't like the independent woman. Oh, she has virtues! But when woman loses her inconsistency and self doubt she loses her charm."

"She needn't. If she's in earnest and loves it, why shouldn't she work and live alone as I do?"

"But you live with your uncle, don't you?"

"No. I am much more comfortable as I am. I came here sure of a small income. I earn that sum twice over now. I live alone, and I'm writing a book."

"Really."

They continued in silence, and then David looked at her squarely.

"I am thinking what an amazing gulf lies between you and your great-grandmother. Wouldn't she scold you if she could come back? Wouldn't she, though?"

"I dare say," said Anne placidly, "but I wouldn't approve of my great-grandmother, nor of my grandmother either."

David threw back his head as a boy does before a shout of laughter, corrected himself and looked at her with weighty seriousness.

"Really, impertinence couldn't go further."

Anne's was both naive and speculative as she continued:

"My grandmothers had no spirit, no originality, went in for artistic fainting and wrote silly love rhymes. They were as savorless as oatmeal without salt, those admirable, chimney corner women. Their husbands thought nothing of crying 'Tush' at them, and they 'tushed' beautifully. Oh, they wouldn't be at all popular today."

"But you are not a new woman?'' said David with some awe.

"No," and the denial was uncompromising. "I hate the new woman, you have not classified me correctly. I hope I am the awakened woman."

"I never heard of her before."

"Well, I'll tell you something about her. Without retaining the womanliness of the clinging heroine of the past and without feeling to a sensible extent a desire for progress she could not exist. She is the result of extremes past and present."

"Many of her?"

"She's everywhere. Her privileges are so many she's busy enjoying them. There's little said about her, but every one who thinks knows she is the woman of today."

Her earnestness made her face strangely lovely, and the thought prompted David's next words.

"Does she like to be pretty?"

"She delights in it. She's not only a good chum with men or a plaything or an intellectual machine; she's a woman," she said, and there was music in the word. "She believes that marrying the man she loves - and she can't love the weak, the stupid, the hopelessly corrupt - is the culmination of the pose for which she was created. She's not ignorant of the existence of evil, but it has not tempted nor hardened her. But best of all, she's not a paragon. Her aspirations are high and good, her faults alluring. Now you know my ideal."

By the time her home was reached they were very well acquainted. Anne felt herself come very near the gentlest side of David's nature as she gave him her hand. He clasped it earnestly as be looked into her untroubled eyes.

"New York is dead in summer time," he said irrelevantly. "All one's friends away! So few people one cares to talk to anyway!"

An unreasoning sense of gladness filled Anne. She knew he was waiting for her to speak.

"Dr. Ericsson spends many of his evenings here. When you feel inclined, come in too."

"I will," he said gratefully.

And he did. Often after busy days during which scarcely a word was exchanged between them he would find himself strolling through the sultry night to the grateful coolness of Anne's rooms. Dr. Ericsson was generally there, but sometimes they were alone.

The unusualness of unhampered comradeship with a bright, young and pretty woman, their long, satisfying talks on subjects whimsically varied, the independence of Anne's solitude, her courageous position as a worker, level with his own as a man, appealed to David with a charm new in his experience.

As he grew more end more interested his visits became more frequent. They became good friends. Sometimes while the moon looked over the roof tops and the candles flamed in the night breeze Anne sang to him. Sometimes Dr. Ericsson and she dined with him, mostly in cool, suburban places, requiring long drives along the almost empty avenues and through the massed shadows of the park. Sometimes on David's roof top, made comfortable with rugs and hammocks, they three saw the day die and the stars gather like eyes to watch the clashing ways of life. Every day his fondness for her deepened. She was his comrade and friend. He felt himself her silent champion and protector.

CHAPTER V.

"Do you think Temple will get here tonight before the paper's out?" And the news editor nervously rolled and unrolled the copy he held.

"When he says he'll do a thing, he does it," said Frawley, the managing editor, who was covering the pages before him with blue lines from his flashing pencil until they looked like map of a railroad that followed an inconsequent course and met in a labyrinth.

Anne looked at the clock. It was after 10. The pencil dropped from her fingers and she pulled the shade from above her tired eyes. Since 7 she bad been writing in a race against time, and now, her work completed, she was tingling with fatigue.

It was the 1st of November. The summer, unlike another of her life, seemed far away. Made up of dusty, feverish days and happy nights, it was past, like a sleep. Through the window before her she could see the fog dripping over the city, a curtain of sootiness, its folds breaking on the angles of houses, the lights of the town white splashes on the haze. The world looked sullen, as if choked under that sooty pall into submission and silence. And yet none knew better than she, sitting aloft among the chroniclers, of the snarl among the unhappy, of the turmoil and crime seething there, and the ambition which spared no brother for the uprising of self.

It had been a day of extraordinary climaxes. A murder in high places had horrified the city. The political struggle was hurrying to a crisis. The latest telegrams told of disastrous floods in one state and a strike of many thousand miners in another.

As a result there were tonight more striking of bells and dragging sound of hurrying feet than were usual even during the exciting hours just previous to the paper going to press. There was expectancy on the absorbed faces. Unrest hung in the air like a stormcloud.

After a week's absence David Temple was momentarily expected. He had wired to suspend any arrangements regarding the assignment of reporters to the scene of the strikes until his arrival. While the usual routine of making the paper went on the men were waiting for him.

Anne was waiting for him too. A trembling anticipation swept over her as she fancied him coming through the open door. He would bring restfulness into the confusion, a visible power to the handling of the several problems, and it would be good to see him again.

"He ought to be here now," said Jack Braidley, strolling over to her desk. "I hope he'll let me out of Platt's Peak. I don't want that assignment. Starving miners are not much in my way."

"I thought not, " said Anne dryly, gathering together the copy headed "The Sunday Page," which during the present stress she edited. "I never saw you look as happy as the day you were sent out to inspect and describe the Duke of Stockbury's wedding clothes when he came over to marry the sugar refiner's daughter. They were in your line."

"Oh, I say, you do chaff a fellow horribly! But seriously, I'm playing for the dramatic critic's place. Jove, fancy calling that work - every pretty actress smiling at you pleadingly! I was made for it. By the way, Miss Garrick, why don't you go on the stage? Beastly work this for a pretty girl!"

Anne was not listening to him. Leaning her elbow on the back of the chair, her hand curved like a cup to support her chin, she was looking at Donald Sefain, who had just come in.

There he was, shabby, silent, a recluse among the alert crowd. The discontent in his worn eyes, his hopeless but unconquered air, seemed now as always like a minor, passionate phrase woven unfittingly into the flourishes of a hackneyed tune.

She wondered if she would ever know him, ever learn just what sinuosities of character, what experiences, had made him the creature he was. This wish had begun to tinge her days. Nothing, however, seemed more unlikely. They had not exchanged a word. He held aloof from her as from every one else.

"Look at that beast Sefain, " muttered Braidley.

"Why do you call him that?" And Anne turned sharply upon him.

"Look at his clothes."

"They're not like the Duke of Stockbury's, are they?"

"Besides he drinks. I saw him drunk once in this very room. It was last spring, I think. His eyes were frightening that day. I expected to have good story about his suicide next morning. But fellows like him never kill themselves."

Anne moved away and stood near Frawley's desk, just as Donald went up to him.

"I want to do the pictures for the Platt's Peak strike," she heard him say in his surly, indifferent tone.

"Mr. Temple attends to that," said Frawley, strolling over to watch the telegrams coming in like mad.

"But I can't wait to see him unless he comes within five minutes. I wish you'd tell him I'd like to go to Platt's Peak. I don't suppose there'll be a rush for the place anyway."

"D----d fussy about his minutes for a beggar," thought Frawley, but answered in a colorless voice, "All right."

Donald slouched over to his desk and picked up his hat. He had neared the door when Frawley, peering over the operator's shoulder at the wire, uttered a cry.

"Good God!"

Consternation and suspense fell upon the place. It was as if a full heart had suddenly ceased beating. In the stillness, the shrill warnings of fog whistles from the bay were eerie, as if witches shrieked at the windows. Donald paused at the door. Anne stood like a stone.

"Hear this. Temple"-- And Frawley sank back into a seat unable to obey his impulse to speak.

"What, for heaven's sake?" And one of the men waiting seized the tape from the operator's fingers.

"Southern express wrecked south of Philadelphia. Many dead. David Temple fatally injured." There was much more. Details followed, speculation, exclamations of dismay and pity, but Anne heard only those last four words. They had descended like a sword, striking strength and motion from her body and all but one thought from her mind. She stood with pale lips, a shadow weighing upon her eyes. She shivered as if in the clammy dusk of death. There was a blur, a grotesque mixing of faces and objects, a sense as of being seized by a horrible separating current and torn away from all things to which she could cling, a sense of crushing loss.

She sat down before her desk facing the black window where the city lights flickered. The horror faded into a passionate cry which, though unuttered, shook her whole being. David among the injured, David far away, not strong and controlling, but lying in voiceless pain under the sullen sky! They said, "Injured fatally." Perhaps it meant dying, perhaps it meant dead. Dead! The word seemed to take her by the throat, hold her, look into her eyes, deep into her heart and laugh at what it saw there.

Nothing in the past mattered beside the rich truth that David had been her friend, nothing in the future beside the craving to touch him and hear him speak her name once more. She knew in a revealing blaze the secret of her heart that before. she had not even dimly understood.

Unconsciously she prayed as she sat there staring into the vacuity of the window. "Save him! I love him, I love him, I love him!" (To be continued)