White Minorities No Longer "Invincible"

By Steve Talbot

What's the word? Tell me, brother, have you heard from Johannesburg?

What's the word? Sister-woman, have you heard 'bout Johannesburg?

They tell me that our brothers over there are defyin' the Man.

I don 't know for sure because the news we get is unreliable, man.

Well, I hate it when the blood starts flowin'

but I'm glad to see resistance growin'.

Somebody tell me, what's the word?

Tell me, brother, have you heard from Johannesburg?

- Gil Scott-Heron

"Johannesburg"

"We did not expect anything like this to happen," Police and Justice Minister Jimmy Kruger told the South African Parliament as 10,000 black high school students battled heavily-armed riot police in the Soweto ghetto, outside Johannesburg. And he meant it. Less than three months ago, Kruger toasted Prime Minister John Vorster at a dinner in his honor, assuring him that there was "no chance of a large-scale insurgency" among South Africa's 18-million black majority.

Kruger, of course, was dead wrong. The white minority has just been shaken by the most violent racial upheaval in modern South African history. Officially, 140 people - almost all black - were killed in nearly a week of street fighting that spread across the country. At least 1,128 people - again almost all black - were reported injured.

But those are the government figures. Black leaders in South Africa (Azania) have notified the United Nations Committee on Apartheid that a thousand or more blacks were killed and thousands wounded. Many were shot by police. Others, according to black observers on the spot, were murdered by white vigilantes known as the Citizens Reserve Force, who were allowed by police to enter ghetto areas like Soweto to restore "law and order". Black leaders informed the U.N. committee that many victims had been killed by .22 caliber bullets-the type commonly used by vigilantes.

Most of the casualties were young. The first fatality, according to black students, was Hector Pearson, 13. The students were unarmed. As the fighting escalated, they faced police armed with automatic rifles, special para-military SWAT-style squads, dogs, helicopters spraying tear gas, and armored cars.

But it was not just a massacre. It was not just a repeat of Sharpeville, 16 years before, when police opened fire on an unarmed crowd of blacks demonstrating against the hated "pass laws" - killing 69 and wounding nearly 200. This time blacks took the offensive, fighting police with anything they could get their hands on - from stones and wooden clubs to iron bars and pickaxes. They burned cars, buses, government buildings, police stations, schools, and beer halls.

According to a preliminary estimate by South African insurance companies, blacks destroyed $34.5 million worth of white-owned property in Soweto alone. Government liquor stores suffered a $10 million loss. At one point during a major battle in Mabopane, outside Pretoria, some 300 blacks stormed a large, white-owned farm on the outskirts of their ghetto - ransacking the house, beating up the owner, and burning the farm to the ground.

There was a new militancy and a new political consciousness apparent among the students who took part in the rebellion. They taunted police, chanted "black power", and sang the nationalist anthem, "God Bless Africa" (Nkosi Sikelele Africa). "Our children are doing what we should have done long ago," David Sibeko, a spokesperson tor the Pan-Africanist Congress (one of South Africa's liberation movements) told the U.N.

While the Western press insisted on calling the uprising a riot, Winnie Mandela - a respected black leader and the wife of the imprisoned president of the African National Congress (the other major liberation group) - told reporters, "This is a rebellion against apartheid." Addressing an emergency session of the U.N. Security Council, Tanzania's ambassador, Salim A. Salim, said the South African regime was facing an uprising by blacks that spells "the beginning of the end of its racist system of apartheid."

Few accused Salim of exaggeration. The Soweto rebellion shattered the illusion of stability and racial balance that the white minority regime was carefully trying to create. It was perfectly timed to sabotage the Kissinger-Vorster talks in West Germany - leaving the Secretary of State hard-pressed to explain why he was meeting with a leader who had ordered his police to shoot blacks demanding racial equality. Kissinger's claim that "the purpose of the meeting is to contribute to a peaceful evolution of the problems of southern Africa" had a hollow ring.

PROGRESSIVE FORCES ON THE MOVE

The Soweto rebellion takes on great significance when seen in the context of recent developments in the southern African region. It was not an isolated outburst. It comes after the victory of FRELIMO, the militant leftist liberation movement, in neighboring Mozambique.

FRELIMO's success in defeating Portuguese colonialism has reportedly left a deep impression on South African blacks. Thousands of miners from Mozambique still enter South Africa and spread the word about the new "black power" and the radical transformations taking place in their country just across the border. A group of South African students - the SASO 9 - are still in jail and are about to go on trial for a pro-FRELIMO rally they took part in nearly two years ago.

The Soweto rebellion also follows the defeat of the South African army in Angola. South Africa's ill-fated invasion of Angola last October marked the first time that the apartheid regime had dared to invade a black-ruled nation. South Africa's defeat at the hands of the MPLA and Cuban forces had a tremendous impact throughout southern Africa - the whites, who claimed "invincibility", had been routed.

Both liberation movements in South Africa - the ANC and the PAC - welcomed the MPLA victory. For one thing, it opened up a secure rear base for SWAPO, the liberation movement trying to drive South Africa out of Namibia (South West Africa). Aided by the MPLA, SWAPO has stepped up its low-level guerrilla war against South African troops. The apartheid regime has been forced to send reinforcements to Namibia, drawing soldiers away from the home front and increasing the opportunities for insurgency in South Africa itself.

An ANC leader recently told Guardian correspondent Wilfred Burchett that the FRELIMO and MPLA victories in Mozambique and Angola had "changed the whole balance of forces in southern Africa . . . The progressive forces are now on the offensive and they will rapidly gather force. For us, this is of particular importance. For the first time we have a genuinely friendly border - denied us ever since the imperialists came to southern Africa."

He added: "It is no secret - certainly not for the South African authorities - that our underground structures have been developed, and that the numbers recently recruited are more than they have been at any time since the ANC national leadership was arrested in 1963 . . . militants, subdued as a result of tremendous repression in recent years, are beginning to surface again."

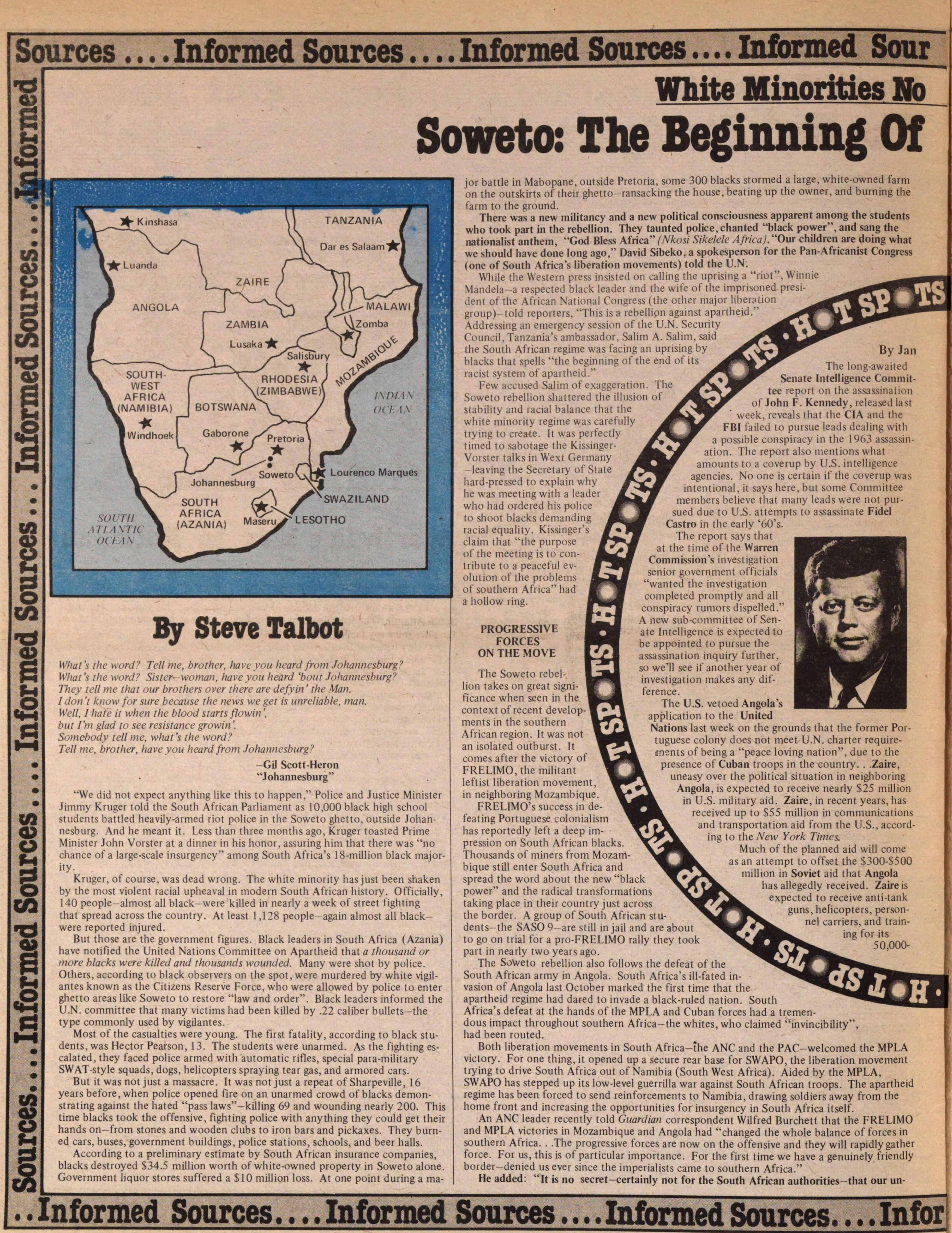

And now there is also the expanding guerrilla wat in Zimbabwe (Rhodesia). A badly splintered liberation movement - hampered by external pressure from countries like Zambia to negotiate with Rhodesia's Ian Smith regime - has now reportedly forged a new unity among guerrilla forces of ZANU and ZAPU committed to unrelenting armed struggle. Based in Tanzania and Mozambique, the united Zimbabwe guerrillas have sabotaged railroads, blocked highways, ambushed Rhodesian army patrols, and struck within 25 miles of Salisbury, the capital.

No one outside Rhodesia's white minority believes the Smith regime can survive. The days of white rule in Rhodesia are numbered, and the United States and South Africa now believe their only hope is to pressure Smith into accepting a peaceful transition to some kind of multi-racial government. If Smith won't budge, it is now clear the U.S. at least is prepared to dump him in order to install a pro-Western "moderate" black regime - anything to prevent another black leftist movement, like FRELIMO or MPLA, from taking power.

Mozambique, Angola, the guerrilla wars in Namibia and Zimbabwe - all are creating enormous opportunities for South Africa's black majority to move against apartheid.

WHITE SOUTH AFRICA'S NIGHTMARE

The Soweto rebellion began as a protest movement against the enforced use of the despised Afrikaans language in teaching black high school students. The grievance against the language was real enough, but it was not the fundamental issue. It was the fuse.

"Afrikaans is the language of the police station, the pass office and the oppressor," wrote the Rand Daily Mail, a relatively liberal opposition paper by South African standards. Afrikaans is derived from Dutch and is the language of the ruling Boer whites. The Sunday Tribune said, "No words are too strong to describe the arrogance and incompetence of Mr. Botha and Dr. Truernicht" -the two notoriously right-wing and racist government ministers in charge of black education, who decreed that black students had to learn math, geography, and history in Afrikaans. (For white students, it was optional.)

Black students in Soweto immediately protested the ruling. They already spoke their tribal language and English and were not about to learn a language which symbolized white oppression and was about as useful as Latin. They began boycotting classes as early as March. The protest grew to include several thousand students. Two days before Soweto exploded, a local black official, Leonard Mosala, warned that the language issue would "result in another Sharpeville if it is not dealt with immediately."

Dr. Treurnicht would not budge an inch. He told a political meeting, "Liberals favor majority rule for Rhodesia and South Africa. All they seek is the blood of the white man. The National Party will not veer from its plan."

When police tried to disperse 10,000 black students marching on June 16 in Soweto to protest the language requirement, the rebellion was on.

This time it was Afrikaans. Next time it will be something else - unemployment, bannings, the lack of free speech, the pass laws, the grinding poverty. As the rebellion spread to other black "townships" around Johannesburg, then to those surrounding Pretoria, and on to the "bantustans" or tribal reservations - it was obvious that more than Afrikaans was at stake. It was apartheid, the entire system of racial separation and white supremacy imposed by South Africa's 4 million whites on 18 million blacks, 2.2 million "coloreds" (mulattos), and 750,000 Asians.

Soweto, for instance, could have exploded over any number of issues. It is a congested black ghetto with as many as one million people - the third largest "city" in South Africa - about 12 miles south of Johannesburg. Like other black townships which surround South Africa's white cities, the population is forced to live there. The government allows the blacks to come out during the day to board crowded, expensive trains and buses to commute into Johannesburg to work in factories and businesses or serve as maids in the "master's" house.

At dusk, all but the live-in "nannies" must return to the ghetto, where only about...

continued on page 24

Article

Subjects

Freeing John Sinclair

Old News

Ann Arbor Sun