Ann Arborites To Make Concrete Ties With Nicaraguans

In January, 25 Ann Arborites will travel to Nicaragua armed with hammers, trowels and electrical conduit to work with Nicaraguans on a solidarity and technical assistance project. In the first construction brigade to represent the state of Michigan, North and Central American plumbers will fit pipes together, Michigan electricians will learn how to wire under an electrical embargo, and local students will exchange views with their Nicaraguan peers. The group is called "AMISTAD," which is the Spanish word for friendship and the acronym for the Ann Arbor-Managua Initiative for Soil Testing and Development. Their goal is to help build a soils and water testing and research laboratory in Managua and to increase cooperation and understanding between the peoples of the U.S. and Nicaragua.

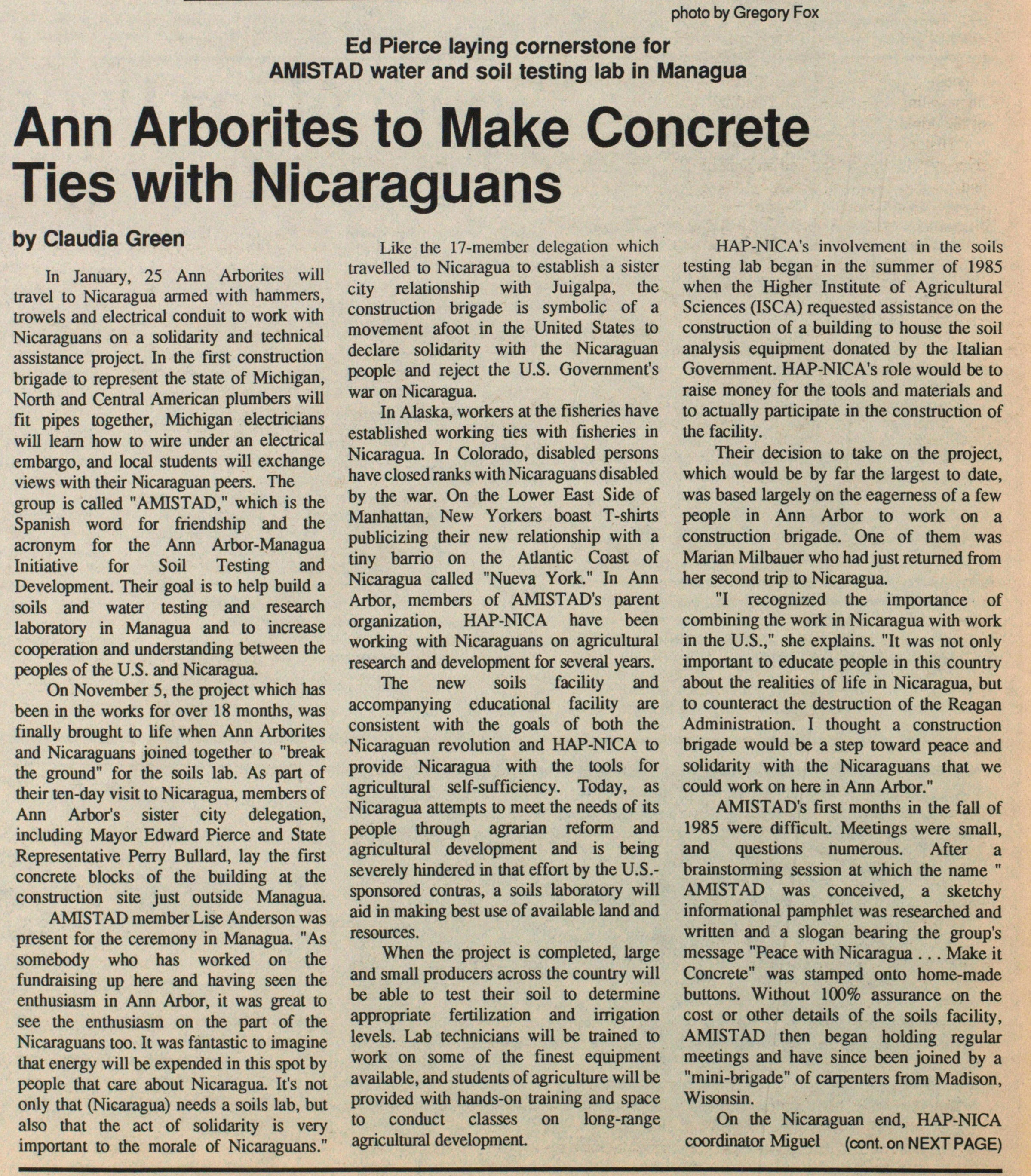

On November 5, the project which has been in the works for over 18 months, was finally brought to life when Ann Arborites and Nicaraguans joined together to "break the ground" for the soils lab. As part of their ten-day visit to Nicaragua, members of Ann Arbor's sister city delegation, including Mayor Edward Pierce and State Representative Perry Bullard, lay the first concrete blocks of the building at the construction site just outside Managua.

AMISTAD member Lise Anderson was present for the ceremony in Managua. "As somebody who has worked on the fundraising up here and having seen the enthusiasm in Ann Arbor, it was great to see the enthusiasm on the part of the Nicaraguans too. It was fantastic to imagine that energy will be expended in this spot by people that care about Nicaragua. It's not only that (Nicaragua) needs a soils lab, but also that the act of solidarity is very important to the morale of Nicaraguans."

Like the 17-member delegation which travelled to Nicaragua to establish a sister city relationship with Juigalpa, the construction brigade is symbolic of a movement afoot in the United States to declare solidarity with the Nicaraguan people and reject the U.S. Government's war on Nicaragua.

In Alaska, workers at the fisheries have established working ties with fisheries in Nicaragua. In Colorado, disabled persons have closed ranks with Nicaraguans disabled by the war. On the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New Yorkers boast T-shirts publicizing their new relationship with a tiny barrio on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua called "Nueva York." In Ann Arbor, members of AMISTAD's parent organization, HAP-NICA have been working with Nicaraguans on agricultural research and development for several years.

The new soils facility and accompanying educational facility are consistent with the goals of both the Nicaraguan revolution and HAP-NICA to provide Nicaragua with the tools for agricultural self-sufficiency. Today, as Nicaragua attempts to meet the needs of its people through agrarian reform and agricultural development and is being severely hindered in that effort by the U.S.-sponsored contras, a soils laboratory will aid in making best use of available land and resources.

When the project is completed, large and small producers across the country will be able to test their soil to determine appropriate fertilization and irrigation levels. Lab technicians will be trained to work on some of the finest equipment available, and students of agriculture will be provided with hands-on training and space to conduct classes on long-range agricultural development.

HAP-NICA's involvement in the soils testing lab began in the summer of 1985 when the Higher Institute of Agricultural Sciences (ISCA) requested assistance on the construction of a building to house the soil analysis equipment donated by the Italian Government. HAP-NICA's role would be to raise money for the tools and materials and to actually participate in the construction of the facility.

Their decision to take on the project, which would be by far the largest to date, was based largely on the eagerness of a few people in Ann Arbor to work on a construction brigade. One of them was Marian Milbauer who had just returned from her second trip to Nicaragua.

"I recognized the importance of combining the work in Nicaragua with work in the U.S.," she explains. "It was not only important to educate people in this country about the realities of life in Nicaragua, but to counteract the destruction of the Reagan Administration. I thought a construction brigade would be a step toward peace and solidarity with the Nicaraguans that we could work on here in Ann Arbor."

AMISTAD's first months in the fall of 1985 were difficult. Meetings were small, and questions numerous. After a brainstorming session at which the name "AMISTAD" was conceived, a sketchy informational pamphlet was researched and written and a slogan bearing the group's message "Peace with Nicaragua . . . Make it Concrete" was stamped onto home-made buttons. Without 100% assurance on the cost or other details of the soils facility, AMISTAD then began holding regular meetings and have since been joined by a "mini-brigade" of carpenters from Madison, Wisconsin.

On the Nicaraguan end, HAP-NICA coördinator Miguel

(cont. on next page)

AuClair-Valdez began working in March of this year to hammer out details and logistics. Eduardo Vera of East Lansing took over this task in October and is now working full time as AMISTAD's project organizer in Managua making preparations for the brigade's arrival. Both of them have played an indispensable role in coordinating the complicated Communications between the U.S. and Nicaragua necessary to make the project go forward.

Fundraising here in Ann Arbor began with a small benefit featuring a local band at the Halfway Inn in East Quad. Soon brigade members were doing everything from collecting cans and bottles, cooking chicken and pasta for thousands of people at the Ann Arbor Art Fair, booking concerts at local bars and organizing an auction and the "Bowl for Peace" Bowl-a-thon.

Early last spring, as brigade members began feeling that their fundraising was alienating them from the political spectrum, they launched plans for a celebration of the seventh anniversary of the Nicaraguan revolution. The July 19th Bash brought together North and Central American solidarity workers, unionists, musicians, poets, and members of the 1936 Lincoln Brigade to celebrate an historical triumph in the struggle against imperialism and oppression. "The anniversary celebration was a public statement that we were not only against the U.S. support of the contra war, but that we support the revolutionary process in Nicaragua," says Milbauer, who helped to organize the event. "On that day we reaffirmed our commitment to the struggle for freedom in Central America and around the world."

Fourteen months of organizing the brigade has brought together a cohesive group of very different people, united by their opposition to intervention and imperialism. The brigade has inspired dialogue, fears, and even participation among friends and family members. For some members of the group, the war that has already taken thousands of lives in Nicaragua and the prospect of increased military aid in early 1987 has caused family tensions surrounding members' decision to go with the brigade in January. The promise

(see AMISTAD, page 31)

of first-hand experience in a country undergoing a revolution has drawn other family members into the group.

In the DeBroux family, 3 out of the 4 brothers are driving taxis in Ann Arbor to make enough money to go to Nicaragua in January. In electrician Don Oswell's family, he has stimulated discussion about Nicaragua and even suggested to his children that they accompany him on his trip to Nicaragua. Don, in his mid-40's, has watched groups like AMISTAD with admiration for years and has finally found a way that he could become involved.

"In the 60s, I saw groups like this going to Cuba, and at that point and time n my life I believed that Cuba was not a threat. I thought those people were very courageous," says Don. "I began to sense that the U.S. response to the Nicaraguan revolution was similar that it was an attempt to maintain control over disadvantaged people in other countries. f saw (AMISTAD) as a creative response to the destruction being done by the contras . . . Building is the thing that I do best in my life, so it's the best contribution I can make."

Don and others in the group have recently been consumed by the gathering of tools and materials to send off to Nicaragua before the group arrives in January. Several tons of equipment, for the most part not available in Nicaragua due to the economic war being waged by the U.S., has been purchased and collected from donors in the area.

In the six weeks still to go before they set off for Managua, brigadistas will be attempting to add an additional $10,000 to the $20,000 they have already raised, to cover additional tool purchases. AMISTAD's work will also continue beyond January. Throughout the projected six months of construction, additional brigadistas will arrive in Nicaragua and others will return to join a support group in Ann Arbor to continue fundraising. A film about the construction brigade is already in the works and will be used for educational and organizing purposes after the work in Nicaragua is completed.

A send off party for the first wave of brigadistas will be held December 19. Information can be obtained at the AMISTAD/HAP-NICA office.

The AMISTAD Construction Brigade is still in need of financial and organizational support. Contact AMISTAD/Guild House, at 802 Monroe, Ann Arbor Mi, 48104 or 761-7960. See CRD.