1986 Looking Back--looking Forward

January is an obvious time to reflect upon the previous year and to speculate on the coming year. AGENDA invited a number of people to write an article on a topic of their choice with a particular emphasis on the relevant happenings of 1986 and if applicable, expectations for 1987. Some of their responses are formal, others are more personal.

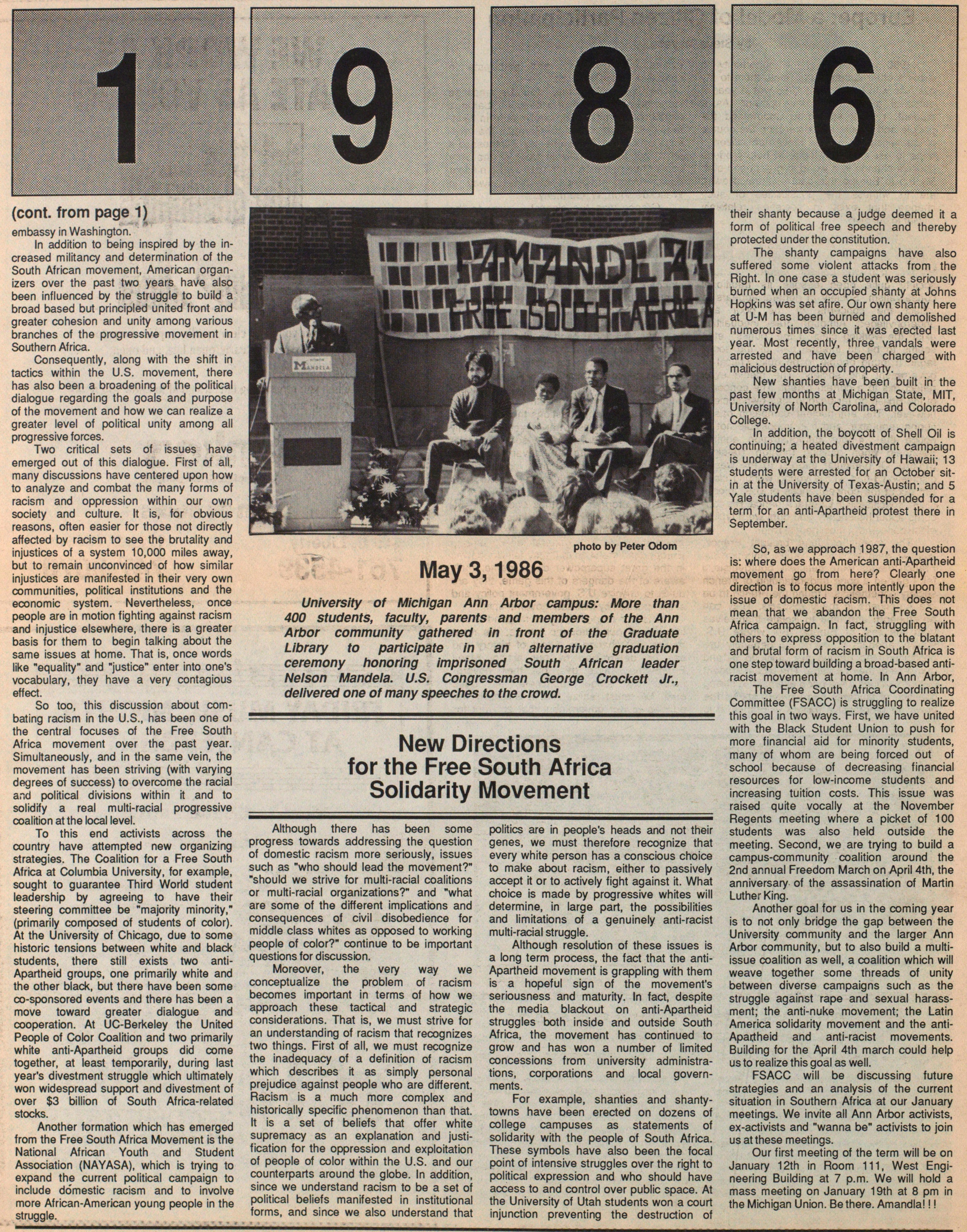

1986 has been an important year for the struggle for freedom within South Africa as well as within the U.S. solidarity movement. Within South Africa itself the struggle has widened and escalated steadily over the past two years bringing the liberation forces ever closer to victory. This escalation, however, has been quite costly in human terms. More than 2,500 Black South Africans have died in the struggle against Apartheid and nearly 25,000 have been jailed over the past two years.

Since the external struggle against the fascist regime in South Africa s pretty clear cut, some of the most critical issues facing the Free South Africa movement this year have been internal ones: the attempt to build a unified and militant trade union movement under the leadership of the recently formed COSATU; the varied campaigns to combat Black collaboration with the regime; the effort to more actively organize progressive whites through the End Conscription (anti-draft) Campaign and the Detainees Parents Support Committee; and finally, the political movement to create a united front against fascism under the banners of the United Democratic Front (UDF), a multi-racial coalition of groups which is posing a greater and greater challenge to the power structure in Pretoria.

The political debates that these organizational efforts have generated are numerous, ranging from the tactics of the armed struggle to the implications of multi-racial (or as South African activists would say, non-racial) coalition building within the context of a racist system and culture. With the goal of a genuinely free South Africa in mind, tens of thousands of South African activists, in secret meetings, in prison cells, and in underground publications, are grappling with these issues and are committed to their ultimate resolution.

Over the past decade American anti-racist activists have looked to our brothers and sisters in South Africa for inspiration and direction, both in terms of how we can be most effective in supporting their liberation struggle, and also in terms of how we can most effectively begin to build our own.

Parallels between the two struggles continue to exist. In 1976 when the Black township of Soweto erupted in protest it sparked a resurgence of the student movement in the United States. Again in 1984 when a series of funeral demonstrations, labor strikes and consumer and rent boycotts led to violent clashes between protesters and the brutal South African military, American activists shifted from educational to more confrontational tactics such as blockades, college campuses sit-ins, and symbolic arrests and pickets in front of the South African embassy in Washington.

In addition to being inspired by the increased militancy and determination of the South African movement, American organizers over the past two years have also been influenced by the struggle to build a broad based but principled united front and greater cohesion and unity among various branches of the progressive movement in Southern Africa.

Consequently, along with the shift in tactics within the U.S. movement, there has also been a broadening of the political dialogue regarding the goals and purpose of the movement and how we can realize a greater level of political unity among all progressive forces.

Two critical sets of issues have emerged out of this dialogue. First of all, many discussions have centered upon how to analyze and combat the many forms of racism and oppression within our own society and culture. It is, for obvious reasons, often easier for those not directly affected by racism to see the brutality and injustices of a system 10,000 miles away, but to remain unconvinced of how similar injustices are manifested in their very own communities, political institutions and the economic system. Nevertheless, once people are in motion fighting against racism and injustice elsewhere, there is a greater basis for them to begin talking about the same issues at home. That is, once words like "equality" and "justice" enter into one's vocabulary, they have a very contagious effect.

So too, this discussion about combating racism in the U.S., has been one of the central focuses of the Free South África movement over the past year. Simultaneously, and in the same vein, the movement has been striving (with varying degrees of success) to overcome the racial and political divisions within it and to solidify a real multi-racial progressive coalition at the local level.

To this end activists across the country have attempted new organizing strategies. The Coalition for a Free South Africa at Columbia University, for example, sought to guarantee Third World student leadership by agreeing to have their steering committee be "majority minority," (primarily composed of students of color). At the University of Chicago, due to some historic tensions between white and black students, there still exists two anti-Apartheid groups, one primarily white and the other black, but there have been some co-sponsored events and there has been a move toward greater dialogue and cooperation. At UC-Berkeley the United People of Color Coalition and two primarily white anti-Apartheid groups did come together, at least temporarily, during last year's divestment struggle which ultimately won widespread support and divestment of over $3 billion of South Africa-related stocks.

Another formation which has emerged from the Free South Africa Movement is the National African Youth and Student Association (NAYASA), which is trying to expand the current political campaign to include domestic racism and to involve more African-American young people in the struggle.

Although there has been some progress towards addressing the question of domestic racism more seriously, issues such as "who should lead the movement?" "should we strive for multi-racial coalitions or multi-racial organizations?" and "what are some of the different implications and consequences of civil disobedience for middle class whites as opposed to working people of color?" continue to be important questions for discussion.

Moreover, the very way we conceptualize the problem of racism becomes important in terms of how we approach these tactical and strategic considerations. That is, we must strive for an understanding of racism that recognizes two things. First of all, we must recognize the inadequacy of a definition of racism which describes it as simply personal prejudice against people who are different. Racism is a much more complex and historically specific phenomenon than that. It is a set of beliefs that offer white supremacy as an explanation and justification for the oppression and exploitation of people of color within the U.S. and our counterparts around the globe. In addition, since we understand racism to be a set of political beliefs manifested in institutional forms, and since we also understand that politics are in people's heads and not their genes, we must therefore recognize that every white person has a conscious choice to make about racism, either to passively accept it or to actively fight against it. What choices made by progressive whites will determine, in large part, the possibilities and limitations of a genuinely anti-racist multi-racial struggle.

Although resolution of these issues is a long term process, the fact that the anti-Apartheid movement is grappling with them is a hopeful sign of the movement's seriousness and maturity. In fact, despite the media blackout on anti-Apartheid struggles both inside and outside South África, the movement has continued to grow and has won a number of limited concessions from university administrations, corporations and local governments.

For example, shanties and shantytowns have been erected on dozens of college campuses as statements of solidarity with the people of South Africa. These symbols have also been the focal point of intensive struggles over the right to political expression and who should have access to and control over public space. At the University of Utah students won a court injunction preventing the destruction of their shanty because a judge deemed it a form of political free speech and thereby protected under the constitution.

The shanty campaigns have also suffered some violent attacks from the Right. In one case a student was seriously burned when an occupied shanty at Johns Hopkins was set afire. Our own shanty here at U-M has been burned and demolished numerous times since it was erected last year. Most recently, three vandals were arrested and have been charged with malicious destruction of property.

New shanties have been built in the past few months at Michigan State, MIT, University of North Carolina, and Colorado College.

In addition, the boycott of Shell Oil is continuing; a heated divestment campaign is underway at the University of Hawaii; 13 students were arrested for an October sit-in at the University of Texas-Austin; and 5 Yale students have been suspended for a term for an anti-Apartheid protest there in September.

So, as we approach 1987, the question is: where does the American anti-Apartheid movement go from here? Clearly one direction is to focus more intently upon the issue of domestic racism. This does not mean that we abandon the Free South Africa campaign. In fact, struggling with others to express opposition to the blatant and brutal form of racism in South Africa is one step toward building a broad-based anti-racist movement at home in Ann Arbor.

The Free South Africa Coordinating Committee (FSACC) is struggling to realize this goal in two ways. First, we have united with the Black Student Union to push for more financial aid for minority students, many of whom are being forced out of school because of decreasing financial resources for low-income students and increasing tuition costs. This issue was raised quite vocally at the November Regents meeting where a picket of 100 students was also held outside the meeting. Second, we are trying to build a campus-community coalition around the 2nd annual Freedom March on April 4th, the anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King.

Another goal for us in the coming year is to not only bridge the gap between the University community and the larger Ann Arbor community, but to also build a multi-issue coalition as well, a coalition which will weave together some threads of unity between diverse campaigns such as the struggle against rape and sexual harassment; the anti-nuke movement; the Latin America solidarity movement and the anti-Apartheid and anti-racist movements. Building for the April 4th march could help us to realize this goal as well.

FSACC will be discussing future strategies and an analysis of the current situation in Southern Africa at our January meetings. We invite all Ann Arbor activists, ex-activists and "wanna be" activists to join us at these meetings.

Our first meeting of the term will be on January 12th in Room 111, West Engineering Building at 7 p.m. We will hold a mass meeting on January 19th at 8 pm in the Michigan Union. Be there. Amandla!!!

Article

Subjects

Barbara Ransby

South Africa

End Conscription Campaign

Detainees Parents Support Committee

United Democratic Front

Free South Africa Coordinating Committee

racism

Coalition for a Free South Africa

Columbia University

University of Chicago

University of California at Berkeley

National African Youth and Student Association

University of Michigan

University of Utah

Michigan State University

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

University of North Carolina

Demonstrations & Protests

Colorado College

University of Hawaii

University of Texas

Yale University

Apartheid

Old News

Agenda

Nelson Mandela

George Crockett Jr

Peter Odom