Secret History Anarchy And Death In Chicago

Secret History

Anarchy and Death in Chicago

A crowd of demonstrators have gathered at a public park in Chicago to listen to revolutionary speeches and to protest for better conditions for workers. Although the rhetoric is fiery, the demonstration is peaceful. The rally is attended by many local dignitaries, including the Democratic Mayor of Chicago. As the Mayor leaves the rally, he directs the police to allow the rally to proceed to its conclusion peacefully. Soon after the mayor leaves, however, a group of more than 200 policemen, acting apparently without orders from higher authority, gather and confront the crowd, demanding that it disperse immediately. As the speakers are leaving the podium to remonstrate with the police, a bomb is thrown into the police lines. More than seventy police are injured, and one is killed. The police open fire on the fleeing crowd. When it is over, the streets run red with blood. Hundreds of demonstrators lie dead or severely wounded in the square.

Is this a scene from 1968? 1970? No, this was Chicago on May 4 of 1886, one hundred and one years ago. Like the other famous killing of demonstrators on May 4, 1970 at Kent State University, the Haymarket Square massacre shocked the conscience of America and helped to shape the future history of the United States. An understanding of the incident is critical in understanding the impact of the radical movement in the United States one hundred years ago.

At this time (c. 1886), anarchists in the United States were in the forefront of militant labor movement in the United States in favor of the establishment of an eight hour work day. Both strikes and unions were illegal at this time in the United States.

The International Working Peoples Party (IWPA) had been founded in 1872 after the split in the Communist Internationale between Marx and Bakunin. The IWPA was the "black," or anarchist, anti-authoritarian wing of the international socialist ment. With the inspiration of many German Socialists who had fled from Bismarck's brutal political purge of 1873, the IWPA formed local working people's associations throughout the United States. The IWPA was one of the wellsprings of the union movement in the United States.

At this time, the right of the people to organize armed militias was still secured by the Second Amendment of the US Constitution. The anarchists organized popular armed militias in Chicago, Detroit, Cincinatti, St. Louis, Omaha, Newark, New York, San Francisco, Denver and other cities.

In 1884, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions passed by a nearly unanimous vote a resolution mandating that eight hours would constitute a legal day's work from May 1, 1886 onward. Another union, the Knights of Labor, added an eight hour plank to its constitution in that same year. During the period spanning 1884 to 1886, the eight hour movement experienced growing support in liberal circles and moderate labor organizations, and was subjected to increasing repression by employers and the state. In 1885, the Metalworkers Union also formed a paramilitary arm, due to the brutal suppression of a strike at the McCormick Harvester (now "Navistar") plant.

On January 4, 1886, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the U.S. Constitution did not include the right of the

(see HAYMARKET, page 23)

Attention Workingmen!

MASS-MEETING

TO-NIGHT, at 7.30 o'clock,

HAYMARKET, Randolph St. Bet. Desplaines and Halsted.

Good Speakers will be present to denounce the latest atrocious set of the police, the shooting of our fellow-workman yesterday afternoon.

Workingman Arm Yourselves and Appear in Full Force!

The Executive Committer.

HAYMARKET (from page 9)

people to form armed militias without the permission of the State. Perforce, the heretofore legal and public workers militias were forced underground. The stage was set for violent confrontation.

On February 16, 1886, another strike at the Chicago McConnick Harvester plant was followed by a lockout, and the hiring of "scab," nonunion, employees.

A nationwide general strike began on May 1, 1886, to bring about the universal adoption of the eight hour work day. Hundreds of thousands of workers joined in. There were scattered incidents of violence throughout the country.

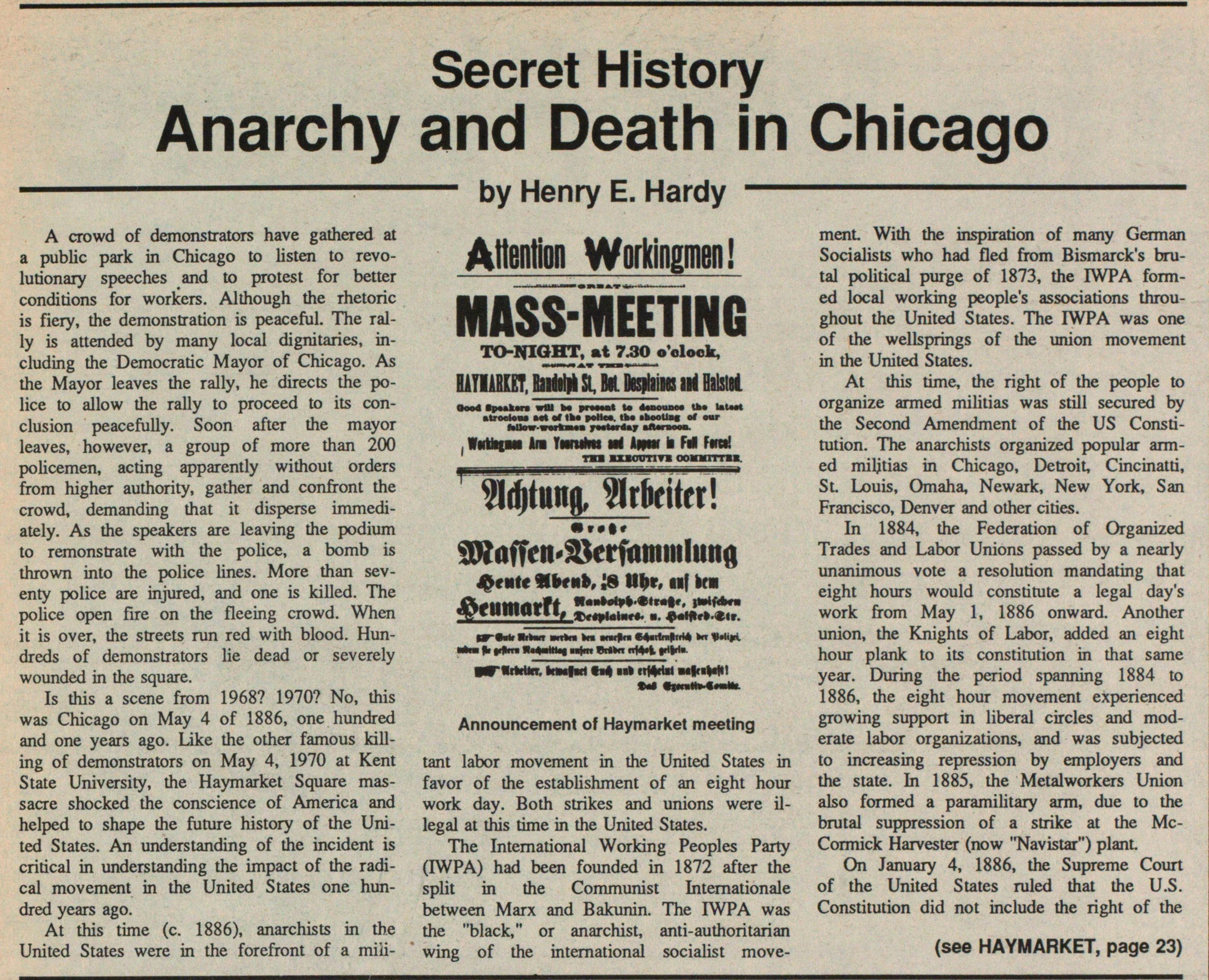

On May 3, one striker was killed and several wounded by police who fired on strikers at the McCormick plant. The anarchist organizer August Spies, mistakenly believing that six strikers had been killed, composed and distributed 10,000 copies of an inflamatory circular calling for a mass meeting on the next day, May 4. The notice, which was entitled, "Revenge! Workingmen! To Arms!," called for armed workers to gather at Chicago's Haymarket Square.

The next afternoon in the square a rally of 20,000 to 25,000 people was held to protest the shootings, and to call for the adoption of the eight hour day and the rest of the anarchist program of worker's democracy. The mayor of Chicago, Carter Harrison, who attended the meeting, observed that it was peaceful. He informed the Chief of Police that no action against the demonstration was necessary, and went home as it began to rain. More than half of the demonstrators also left around the same time, as the rally was almost over and the weather was becoming inclement.

Soon after the Mayor had left the demonstration, a skirmish line of over 200 policemen formed up and ordered the meeting to disperse. By this time, about three quarters of the demonstrators had already departed.

The speakers, including August Spies and others, moved to comply with the police order, descending from the platform as the police formation advanced on the crowd.

Suddenly, a bomb was thrown into the middle of the approaching group of officers. More than 70 policemen were instantly killed or wounded. Police opened fire on the fleeing crowd, killing at least two and injuring hundreds of people. Estimates of the casualties among the demonstrators range as high as 600 people.

In the anti-anarchist hysteria which followed this incident, hundreds of anarchists were harrassed or tortured by vigilante mobs. Newspaper editorials called for the summary deportation, or even immediate execution, of all anarchists.

Spies and six other anarchists were sentenced to death for murder despite the lack of any evidence whatsoever connecting the defendants to the bomb-thrower, whose identity has never been determined. One of the condemned men, Lingg, was found dead in his cell while awaiting execution. On November 11, 1887, Spies and three others were executed by hanging. The others were eventually pardoned. The men remained true to their beliefs to the end.

"Long live anarchy!" was Spies' last cry as the noose was tightened around his neck. For those who are interested in learning more about the anarchist movement and the Haymarket Square incident, I would like to recommend three books: The History of the Haymarket Affair. by Henry David; The Haymarket Tragedy. by Paul Avrich; and the first volume of Emma Goldman's remarkable autobiography, Living My Life.

As a final, personal note, I would like to solicit the comments of you readers. Since you got this far, you must have read most of the article. Please send Letters to the Editor at P.O. Box 3624, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. Please send praise, commentary, reaction, and criticism about this and other editions of "Secret History." Long Live Anarchy!

Next month: "Nicola Tesla: The Man Who Invented Radio, Hydroelectric Power, and the Alternating Current."