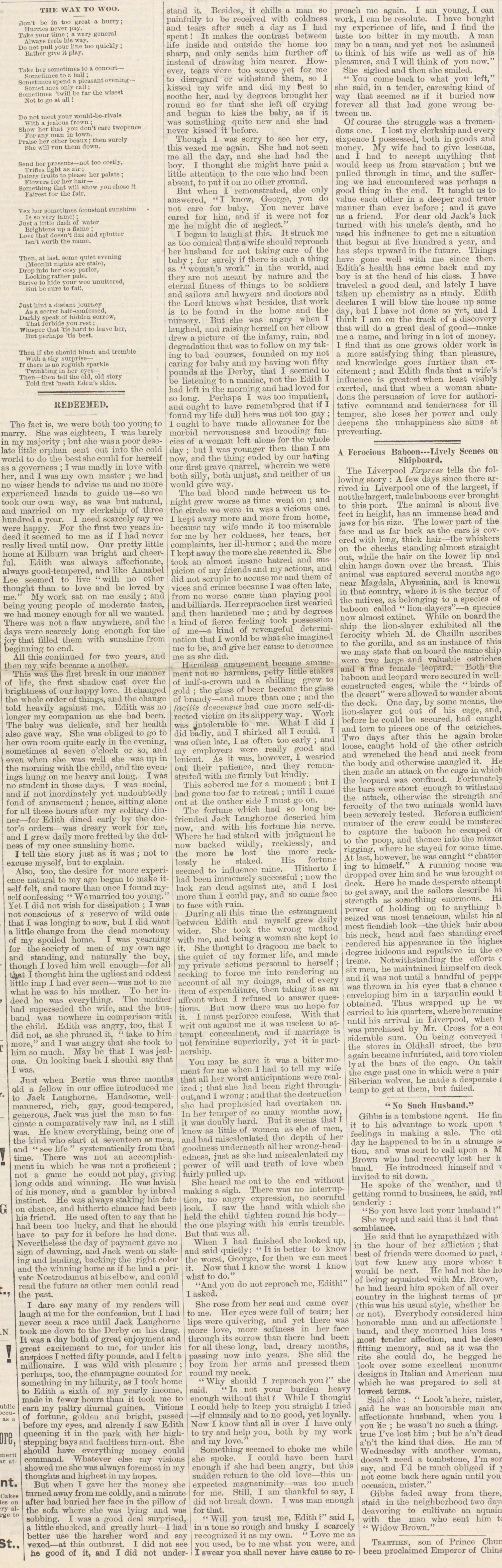

Redeemed

The fact is, we were botli too young to marry. Slio was eighteen, I was barely in my majority ; but she was a poor desolate little orphan sent out into the cold world to do the best sho could for herself as a governess ; I was madly in love with lier, and I was my own master ; we liad no wiser heads to advise us and no more experienced hands to guide us - so wo took our own way, as waa but natural, and married on my elerkship of three hundred a year. I need scarcely say we were happy. Por the flrst two years indeed it seemed to me as if I had never really lived until now. Our pretty little home at Kilburn was bright and cheerful. Edith was always affectionate, always good-tempered, and like Annabel Lee seemed to live "with no other thought than to love and be loved by me." My work sat on me easily ; and being young people of moderate tastes, we had money enough for all we wanted. There was not a flaw anywhere, and the days were scarcely long enough for the joy that filled them with sunshine from beginning to end. All this continued for two years, nnd then my wife became a mother. This was the first break m our marnier of life, the first shadow cast ovor the brightness of our happy love. It changed the whole order of thiugs, and the change told heavily against me. Edith was no longer my companion as she had been. The baby was delicate, and her health nlso gave way. She was obliged to go to her om room quite early in the evening, sometimes at seven o'clock or so, and even when she was well she was up in the morning with the child, and the even.. ings hung on rne heavy and long. I was no student in those days. I was social, and if not inordinately yet undoubtedly fond of amusement ; henee, sitting alone for all these hours after my solitary dinner - for Edith dined early by the doctor'fl orders - was dreary work for me, and I grew daily more fretted by the dulness of my once sunshiny home. I teil the story just as it was ; not to excuse myself , but to explain. Also, too, the desire for moro experience natural to my ago began to inako itself feit, and more than once I found niyself conf essing " We married too young." Yet I did not wish for dissipatioii ; I was not conscious of a reserve of wild oats that I was longing to sow, but I did want a little cbange from tho dead monotony of my spoiled homo. I was yearning for the society of men of my own age and standing, and naturally the boy, though I loved liim well enough - for all %it I thought him the ughest and oddest little imp lliad ever seen - was not to mo what he was to his mother. To her indxxl he was eVerything. The mother had Kivperseded the wife, and Üie husband was nowhere in oomparison with the child. Edith was angry, too, that I did not, as she phrased it, ' ' take to liim more," and I was angry that she took to him so much. May be that I was jealous. On looking back I should say that I was. Jnst wlien Bertio was threo inonths oíd a fellow in our office introduced me ■ o Jack Langhorne. Handsorne, maunered, rioh, gay, good-tenipered, generous, Jack was rast the man to fascinate a comparatively raw lad, as I still i ■wtxa. Ho knew evorytliing, being one of ,he kind who start at se venteen as men, and " Ree life " fsystematically from that ime. There was not an acoomijlisliment in whicli he was not a proflcient ; not a game he conld not play, giving long odds and winning. He "was lavisli of his money, and a gamblor by inbred instinct. He was always staldng his fate on chance, and hitherto cliauce had been his friend. He need oftcn to say that he liad been too lucky, and that he should havo to pay for it before lie had done. Nevertheless tlie day of payment gave no sign of dawning, and Jack went on staking and landing, baeking the right color and tho winning liorse as if he had a private Nostroclamus athiselbow, and could read the future as other men could read the past. I daré say many of my readers will laugh at me for the confession, but I liad nover seen a race until Jack Langhome took me down to tlie Derby on his drag. It was a day both of groat enjoyment and great exeiteniant to me, for under lus ; auspices I nettod fifty pounda, and I feit a milïiouaire. I was wild with pleasure ; )erliaps, too, the champagne counted for iomethiug in my hilarity, as I took home to Edith a sixth of my yesirly income, made ia fewer honrs than it took me to j earn my paltry diiirnal guinea. Visions of fortune, gjlden and bright, passed jefore my eyes, and already I saw Edith queening it in tlie park with her liighstepping bays and faultlesa tum-out. H)ie should have everything money could command. Whatever elae my visions j showed me she was always foremost in my thoughts and highest 111 my hopes. But wlien I gave lier the money she turned away frora me coldly, and a minute after had buried her face in the pillow of the sofa wlierc she was lying and wüb sobbing. I was a good deal surprised, a little ahosked, and greatly luirt - I had better use the harsher word and say yexed - at tliis outburst. I did not see be good of it, and I did not stand it. Besides, it chills a man so painfully to be reoeived with coklness and tears after sucli a day as I liad spent ! It makos tho contrast between life iuside and outside the home too Bharp, and only sends him further off instead of drawing him nearer. However, toars were too scarce yet for me to diaregard or withstand them, so I kissed my wifo and did my Best to soothe her, and by degrees brought her round so fax that she left off cryiug and began to kiss the baby, as if it was something quite new and she had nover kisaod it before. Though 1 was sorry to see her cry, this vexed me again. She liad not seen i me all tho day, and she had had the i boy. I thought she might have paid a litíle attention to the one who had been absent, to put it on no other ground. But when I remonstrated, she only answered, "I know, George, yon do not caro for baby. You never have cared for him, and if it were not for me he might die of neglect." I begíin to laugh at this. It struck me as too comical that a wiíe should reproach her husband for not taking care of the baby ; for surely if there is such a thing as " woman's work" in the world, and they are not meaut by nature and the eternal fitness of tliings to be soldiers aud Bailors and lawyers and doctors and the Lord knows what besides, that work is to be found in the home and the nursery. But sho was angry when I laughed, and raising herself on her elbow drew a picture of the infamy, ruin, and degradation that was to follow on my taking to bad courses, founded on my not caring for baby and my having won fifty ■ pounds at the Derby, that I seemed to be listening to a maniac, not the Edith I had left in the morning aud had loved for so long. Perhape I was too impatient, and ought to have remembered that if I fonnd my life dull hers was not too gay ; I ought to have made allowance for the morbid nervousness and brooding fancies of a woman lcft alone for the whole clay ; bnt 1 was yomiger theu than I am iiow, and the thing ended by our hating our flrst grave quarrel, wherein we were both silly, both unjust, and neither of us would give way. The bad blood made between us tonight grew worse as time went on ; and the eircle we wero in was a vicious one. I kept away more and more from home, j because my wife made it too miserable for me by her coldness, her tears, her complainte, her ill-humor ; and the more I kept away the more she resented it. She took an almost insane hatred and suspicion oL my friends and my actions, and did not scruple to accuse me and them of j vices and crimes because I was often late, from no worse cause than playing pool andbilliards. Herrepraoches first wearied and Uien hardened me ; and by degrees a kind of fierce feeling took possession of me- a kind of revengeful detcrmiïatiou that I would be what she imagined me to be, and give her cause to denounce me as she did. Hnnnless amusement bocame amusenent not bo harmless, petty little stakes of half-a-crown and a shilling grew to gold ; the glass of beer became the glass of brandy - and more than one ; and the faeilis descensus had. one more self-directed victim on its slippery way. Work was. intolerable to me. What I did I did badly, and I shirked all I could. I was ofteñ late, I as often too early ; and my employei-3 were really good and lenient. As it was, however, I wearied out their patience, and thoy remonstrated with me tirmly but kindly. This sobered me for a moment ; but I had gone too far to reteea ; until I carne out at the onther sido I must go on. The fortune which had so long friended Jack Langhorne deserted liim now, and with lús fortune his neire. Where lie had staked with judgmcnt he nuiv baoked wüdly, recklessly, and the more he lost the more recklosely he staked. His fortune seemed to influence mine. HiÜiorto I had been immensely successful ; now the luck ran dead against me, and I lost more than I cotüd pay, and so carne face to face with rubí. During all thifi time tlie estrangnvut between Edith and myself grew daily wider. She took the wrong method with me, and being a woman she kept to it. She thought to dragoon me back to the quiet of my former life, and made my private actions personal to herself ; seeking to forcé me into rendering an account of all my doings, and of every item of expenditure, then taking it as an affront when I refused to answer questioiiK. But now thera was no hop for it. I must perforce confess. With that w'rit out against me it was useless to attempt concealment, and if niarriage is not feminine superiority, yet it is partnership. You may be sure it was a bitter moment for me when I liad to tell my wife that all her worst antuaparaons were reaiizetl ; that ahe liad been right throughout,and I wrong ; and that tbe destruction slie' had prophoaicd had overtaken us. In her temper of so many raonths now, it was doubly hard. But it seems that I knew as little of women as she of men, and had misealonlated the depth of her goodness underneath all her wrong-headedness, just as sho had miscalculated my power of wül and truth of love when fairly pnlled up. She heard me out to tho end without making a sigli. There was no interruption, no angry expression, no scornful look. I saw the hand with which she held the child tighten round lús body- tlie one playing with lus curia trernble. But that was all. Wlion I liad fhnshecl slie looked up, and said quietly: " It is better to know the worst, George, for then we can meet it. Now tliat I know the worst I know what to do." "And you do not reproach me, Edith?" I asked. She rose from her seat and carne over to me. Her eyes were f uil of tears; her lips wero quivering, and yet there was more love, more softness in her face through it sorrow than there had been for all these long, bad, dreary months, passing now into years. She slid the boy from her arms and pressed them ] round my neck. , "Wliy slioukl I rcproacli yon 't" she . said. " Ib not your burden hcavy ■ enough without that ' While I thought I coidd help to keep yon straight I tried - ií clumsily and to no good, yet loyally. Now I know that all is over 1 have only to try and hel]) you, both by my work and my love." Something seemed to choke me white j sho spoke. I could have been hard ! enough if she had been angry, but this sudden return to toe oia love - tms unexpected magnanimity - waa too ïmicb for me. Still, I am thnnkful to Bay, I ': did not break down. I was man enough . for tliat. " Will you trust me, Edith 1" said I, j in a tone so rough and husky I scarcely recognized it as my own. " Love me as you used, be to me what you were, and I sweax you shall never have cause to proaoh me again. I am young, I can Work, I can be resolute. I have bought my cxperience of life, nnd I find the taste too bitter in my mouth. A man uiay be a man, and yet not be asliamed to think of lus wife as well as of bis pleasures, and I will tbiuk of you now." She siglied and tlien slie smiled. " You come bnck to what yon left," i alie said, iu a tender, caressing kind of ■way that seemed as if it buried now forever all tliat liad gone wrong between us. Of course the struggle was a treinendous one. I lost my clerkship and every sixpence I possessed, both in goods and money. My wife had to give lessons, and I had to accept aiiything that j would keep us from starvation ; but we pulled tlirough in time, and tho suffering we had encountered was perhaps a good thing in the end. It taught us to j value each other in a deeper and truer manner than ever before ; and it gave us a friend. Por dear old Jack's luck turned with his uncle's death, and he used his influence to get me a situation that began at live lmndred a year, and has stops upward in the future. Things have gone well with me since then. Edith's health has como back and my boy is at the head of his class. I have traveled a good deal, and lately I have taken up chemistry as a study. Edith j declares I will blow the house up some j day, but I have not done so yet, and I think I am on the track of a discovery that will do a great deal of good - make me a name, and bring in a lot of money. ■ 1 liud that as one grows older work is J a more satisfying thing than pleasure, and knowledge goos further than excitement ; and Edith finda that a wife's influence is greatest when least visibly ! exerted, and that when a woman abandons the persuasión of love for authoritative command and tenderness for ill temper, she loses her power and only deepens tho luihappiness she aims at j preventing.

Article

Subjects

Old News

Michigan Argus