Gelman Second Worst Environmental Disaster In Michigan

Gelman Second Worst Environmental Disaster in Michigan

by Jeff Gearhart and Mark Weinstein

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has called toxic chemical contamination "the most grievious error in judgement we as a nation have ever made." Scio township and Ann Arbor residents have become painfully aware of this in their effort to get water pollution in the vicinity of Gelman Sciences, Inc. cleaned up. Last month the site was ranked second worst environmental hazard in Michigan. Despite this high ranking, there is no evidence that the contamination has stopped or that cleanup of the site will be initialed in the near future.

Gelman Sciences, Inc., which is located on 600 S. Wagner Road in Scio Township, has used dioxane to make filters since the mid-1960s. As early as 1978, there were warnings of the dioxane contamination which was "officially" discovered in 1984. Today this contamination has spread over two miles from the Gelman site. In a May 22 letter to The Ann Arbor News an official in the EPA's Hazardous Waste Enforcement Branch said this contamination has caused ". . . terrible public health and environmental problems that were created by the unscientifically sound and unconscionable act of disposing of tons of dioxane, a known animal carcinogen, into a sand-and-gravel, unlined backyard waste pond as a means to get rid of Gelman's industrial wastes."

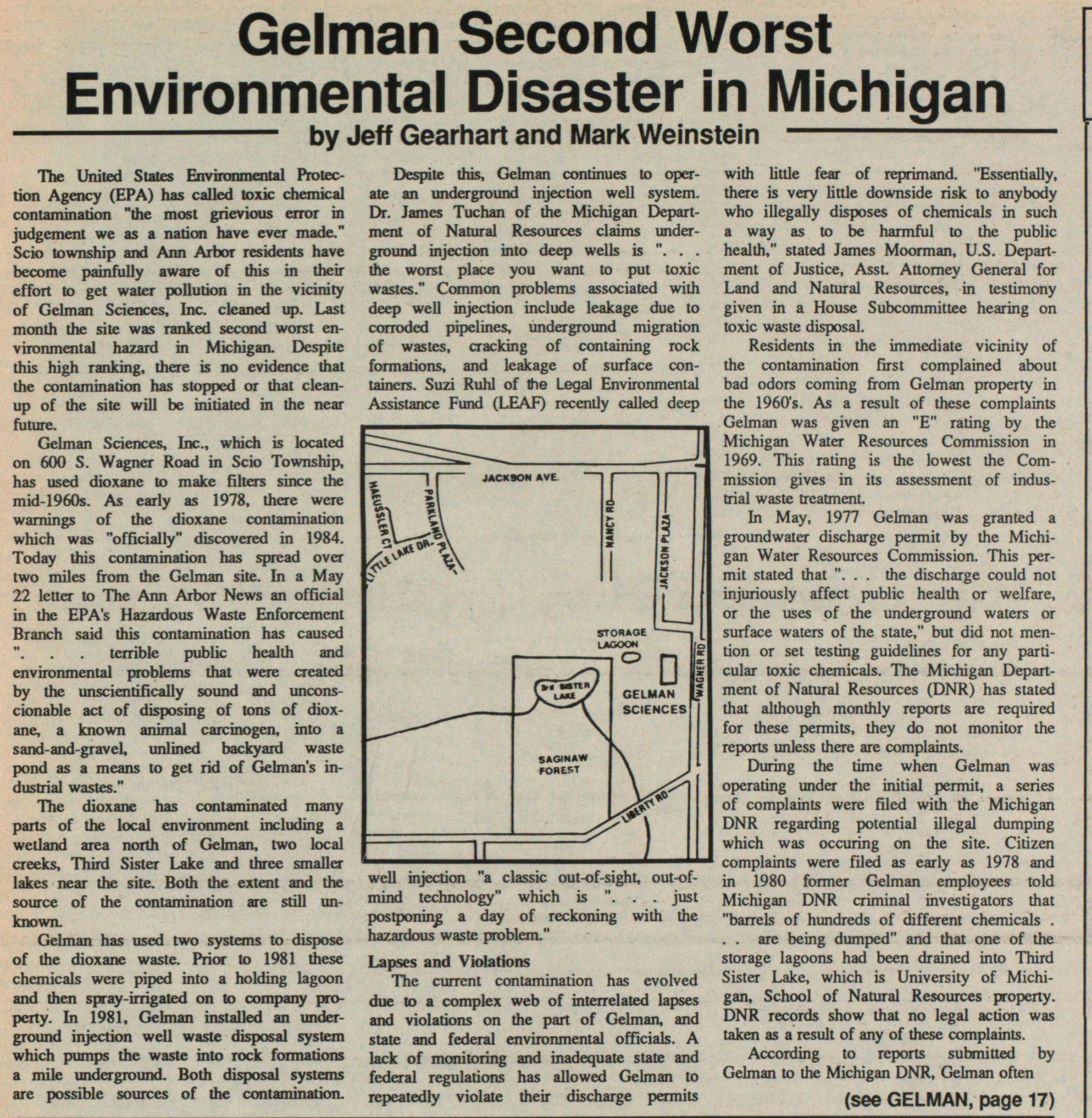

The dioxane has contaminated many parts of the local environment including a wetland area north of Gelman, two local creeks, Third Sister Lake and three smaller lakes near the site. Both the extent and the source of the contamination are still unknown.

Gelman has used two systems to dispose of the dioxane waste. Prior to 1981 these chemicals were piped into a holding lagoon and then spray-irrigated on to company property. In 1981, Gelman installed an underground injection well waste disposal system which pumps the waste into rock formations a mile underground. Both disposal systems are possible sources of the contamination.

Despite this, Gelman continues to operate an underground injection well system. Dr. James Tuchan of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources claims underground injection into deep wells is "... the worst place you want to put toxic wastes." Common problems associated with deep well injection include leakage due to corroded pipelines, underground migration of wastes, cracking of containing rock formations, and leakage of surface containers. Suzi Ruhl of the Legal Environmental Assistance Fund (LEAF) recently called deep well injection "a classic out-of-sight, out-of mind technology" which is ". . . just postponing a day of reckoning with the hazardous waste problem."

Lapses and Violations

The current contamination has evolved due to a complex web of interrelated lapses and violations on the part of Gelman, and state and federal environmental officials. A lack of monitoring and inadequate state and federal regulations has allowed Gelman to repeatedly violate their discharge permits with little fear of reprimand. "Essentially, there is very little downside risk to anybody who illegally disposes of chemicals in such a way as to be harmful to the public health," stated James Moorman, U.S. Department of Justice, Asst. Attorney General for Land and Natural Resources, in testimony given in a House Subcommittee hearing on toxic waste disposal.

Residents in the immediate vicinity of the contamination first complained about bad odors coming from Gelman property in the 1960's. As a result of these complaints Gelman was given an "E" rating by the Michigan Water Resources Commission in 1969. This rating is the lowest the Commission gives in its assessment of industrial waste treatment.

In May, 1977 Gelman was granted a groundwater discharge permit by the Michigan Water Resources Commission. This permit stated that "... the discharge could not injuriously affect public health or welfare, or the uses of the underground waters or surface waters of the state," but did not mention or set testing guidelines for any particular toxic chemicals. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has stated that although monthly reports are required for these permits, they do not monitor the reports unless there are complaints.

During the time when Gelman was operating under the initial permit, a series of complaints were filed with the Michigan DNR regarding potential illegal dumping which was occuring on the site. Citizen complaints were filed as early as 1978 and in 1980 former Gelman employees told Michigan DNR criminal investigators that "barrels of hundreds of different chemicals . . . are being dumped" and that one of the storage lagoons had been drained into Third Sister Lake, which is University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources property. DNR records show that no legal action was taken as a result of any of these complaints.

According to reports submitted by Gelman to the Michigan DNR, Gelman often

(see GELMAN, page 17)

Gelman (from page 3)

exceeded permitted levels for daily discharge and nutrient content between 1980 and 1982. These violations were either not noticed or ignored.

On April 30th, 1982, when deep wells were still under state jurisdiction, Gelman's initial groundwater discharge permit expired but the company was allowed to continue to legally operate for two and a half years while their current application was being reviewed. In September, 1984, after seven and a half years of discharging dioxane on this permit, the Michigan DNR finally notified Gelman that their permit did not allow them to dispose of dioxane and olher organic chemicals. The toxic hazard was confirmed in 1985 when the site was given the 89th worst rating in the state on the Priority List of Michigan Sites of Environmental Contamination.

In early 1986 residents of the area were notified by county health officials not to use the contaminated water for drinking, bathing and washing dishes, and Gelman made arrangements for the affected residents to bathe at a local Holiday Inn. At the same time U.S. EPA officials began sampling the soil, water, and sediments of the area to document the extent of the contamination. Four months after the samples were taken it was reported that the results had to be thrown out because the testing lab failed to meet qualily assurance standards. To date, these samples have not been repeated. Currently, Gelman continues to dispose of its wastewater into the underground injection well even though there is evidence to suggest it might be a contributing source of the contamina tion.

While some corrective actions have been taken by Gelman, the company has not done anything to reverse the environmental damage which has occured. Moreover, Gelman has repeatedly downplayed the danger of the contamination. As recently as 1984 they requested that their site be removed from the Priority List of Michigan Sites of Environmental Contamination. In April 1987 the site was declared the second most hazardous site in Michigan. Yet the company continúes to urge the public not to be preoccupied with the problem.

Citizen Action

While Gelman continues to study what may be an expanding plume of contamination people are bccoming increasingly insistent that a clean up begin. Last year a series of heavily attended hearings were held as the scope of the problem unfolded. Many residents came prepared with questions and felt that they only received lip service from company and government officials. One arca resident described the situation saying, "One of the most frustrating things for me was that the County Health Department and other govemmental cies did not communicatc with us al all. Most of the information we received was through other neighbors or by other unofficial means. So, I didn't know if the information I was receiving was reliable and what steps we could or should take next."

Many residents who had been receiving bottled water were fïnally hooked up to the Arm Arbor city water lines last year. For them the cost of the groundwater contamination was annexation from Scio Township to Ann Arbor. This meant a higher property tax rate, and monthly water bilis in place of previously free well water. This change in the status of the locality has created bilterness among residents who claim that they have already suffered enough and believe that Gelman should be required to bear the full economic and political consequences of the contamination.

In the fall of 1986, as part of its assumption of jurisdiction over deep wells, the EPA held hearings on the federal permitting of Gelman's deep well. Residents of the affected area challenged the EPA's intention to grant the permit in public tcstimony.

During this period, a coalition of affected cilizens established the group "Tocsin." (Tocsin is a word for the sounding of a warning bell.) In January, Tocsin uncovered and released information conceming a leak which had developed in the deep well's injection tubing; information which Gelman, the DNR, and the EPA failed to release. Since that time the DNR and the EPA have been more forthcoming in revealing subsequent problems at the site. Toscin has been reviewing data on groundwater contamination and keeping the pressure on the DNR to have Gelman begin groundwater clean up. In addition, the group is exploring and encouraging the development of altemative methods of waste disposal by Gelman.

Presently, the coalition is requesting a judicial review of the EPA regional decision to grant a permit to Gelman. The groups' efforts have been supported by letters to officials in Washington and more than 1,700 signatures collected on two petitions. Tocsin claims the regional EPA evaluated the well using flawed data, analyses that are often superficial and incomplete, and interpretations of fact that are grossly inacurate. The U.S. EPA's Chief Judicial Officer is considering the requests for a review.

Meanwhile, the EPA continues to allow operation of the deep well despite citizens' concerns of health hazards, continuing environmental damage and the possibility of leakage from the deep well.

In the next issue, the authors will examine community attitudes and actions in relation to this local crisis.

Article

Subjects

Mark Weinstein

Jeff Gearhart

Pall Gelman Dioxane Groundwater Contamination Cleanup History

Dioxane Plume

Gelman Sciences Inc.

Groundwater Contamination

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR)

Legal Environmental Assistance Fund (LEAF)

Old News

Agenda