Ann Arbor's Oldest & Biggest Trees Giants Among Us

Ann Arbor's Oldest & Biggest Trees April 1997 Agenda-5

Giants Among Us

By Arwulf Arwulf

Special To Agenda

O flourish, hidden deep in fern,

Old oak, I love thee well;

A thousand thanks for what I learn

And what remains to tell.

-Alfred Tennyson, "The Talking Oak"

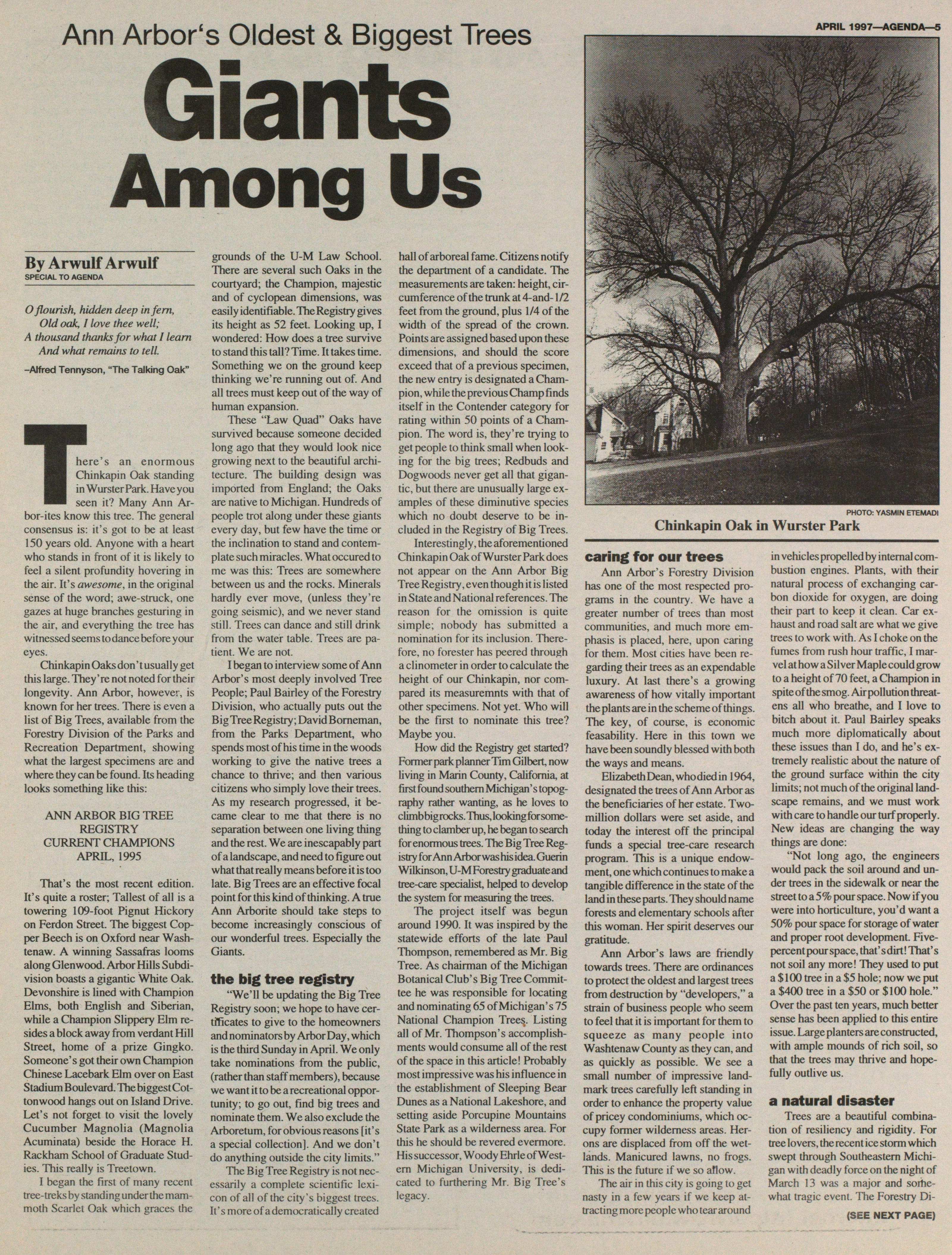

There's an enormous Chinkapin Oak standing in Wurster Park. Have you seen it? Many Ann Arbor-ites know this tree. The general consensus is: it's got to be at least 150 years old. Anyone with a heart who stands in front of it is likely to feel a silent profundity hovering in the air. It's awesome, in the original sense of the word; awe-struck, one gazes at huge branches gesturing in the air, and everything the tree has witnessed seems to dance before your eyes.

Chinkapin Oaks don't usually get this large. They're not noted for their longevity. Ann Arbor, however, is known for her trees. There is even a list of Big Trees, available from the Forestry Division of the Parks and Recreation Department, showing what the largest specimens are and where they can be found. lts heading looks something like this:

ANN ARBOR BIG TREE

REGISTRY

CURRENT CHAMPIONS

APRIL, 1995

That's the most recent edition. It's quite a roster; Tallest of all is a towering 109-foot Pignut Hickory on Ferdon Street. The biggest Copper Beech is on Oxford near Washtenaw. A winning Sassafras looms along Glenwood. Arbor Hills Subdivision boasts a gigantic White Oak. Devonshire is lined with Champion Elms, both English and Siberian, while a Champion Slippery Elm resides a block away from verdant Hill Street, home of a prize Gingko. Someone's got their own Champion Chinese Lacebark Elm over on East Stadium Boulevard. The biggest Cottonwood hangs out on Island Drive. Let's not forget to visit the lovely Cucumber Magnolia (Magnolia Acuminata) beside the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies. This really is Treetown.

I began the first of many recent tree-treks by standing under the mammoth Scarlet Oak which graces the grounds of the U-M Law School. There are several such Oaks in the courtyard; the Champion, majestic and of cyclopean dimensions, was easily identifiable. The Registry gives its height as 52 feet. Looking up, I wondered: How does a tree survive to stand this tall? Time. It takes time. Something we on the ground keep thinking we're running out of. And all trees must keep out of the way of human expansion.

These "Law Quad" Oaks have survived because someone decided long ago that they would look nice growing next to the beautiful architecture. The building design was imported from England; the Oaks are native to Michigan. Hundreds of people trot along under these giants every day, but few have the time or the inclination to stand and contemplate such miracles. What occured to me was this: Trees are somewhere between us and the rocks. Minerals hardly ever move, (unless they're going seismic), and we never stand still. Trees can dance and still drink from the water table. Trees are patient. We are not.

I began to interview some of Ann Arbor's most deeply involved Tree People; Paul Bairley of the Forestry Division, who actually puts out the Big Tree Registry; David Borneman, from the Parks Department, who spends most of his time in the woods working to give the native trees a chance to thrive; and then various citizens who simply love their trees. As my research progressed, it became clear to me that there is no separation between one living thing and the rest. We are inescapably part of a landscape, and need to figure out what that really means before it is too late. Big Trees are an effective focal point for this kind of thinking. A true Ann Arborite should take steps to become increasingly conscious of our wonderful trees. Especially the Giants.

the big tree registry

"We'll be updating the Big Tree Registry soon; we hope to have certïficates to give to the homeowners and nominators by Arbor Day, which is the third Sunday in April. We only take nominations from the public, (rather than staff members), because we want it to be a recreational opportunity; to go out, find big trees and nomínate them. We also exclude the Arboretum, for obvious reasons [it's a special collection]. And we don't do anything outside the city limits."

The Big Tree Registry is not necessarily a complete scientific lexicon of all of the city's biggest trees. It's more of a democratically created hall of arboreal fame. Citizens notify the department of a candidate. The measurements are taken: height, circumference of the trunk at 12 feet from the ground, plus 14 of the width of the spread of the crown. Points are assigned based upon these dimensions, and should the score exceed that of a previous specimen, the new entry is designated a Champion, while the previous Champ finds itself in the Contender category for rating within 50 points of a Champion. The word is, they're trying to get people to think small when looking for the big trees; Redbuds and Dogwoods never get all that gigantic, but there are unusually large examples of these diminutive species which no doubt deserve to be included in the Registry of Big Trees.

Interestingly, the aforementioned Chinkapin Oak of Wurster Park does not appear on the Ann Arbor Big Tree Registry, even though it is listed in State and National references. The reason for the omission is quite simple; nobody has submitted a nomination for its inclusion. Therefore, no forester has peered through a clinometer in order to calculate the height of our Chinkapin, nor compared its measurements with that of other specimens. Not yet. Who will be the first to nomínate this tree? Maybe you.

How did the Registry get started? Former park planner Tim Gilbert, now living in Marín County, California, at first found southern Michigan's topography rather wanting, as he loves to climbing rocks.Thus, looking for something to clamber up, he began to search for enormous trees. The Big Tree Registry for Ann Arbor was his idea. Guerin Wilkinson, U-M Forestry gradúate and tree-care specialist, helped to develop the system for measuring the trees.

The project itself was begun around 1990. It was inspired by the statewide efforts of the late Paul Thompson, remembered as Mr. Big Tree. As chairman of the Michigan Botanical Club's Big Tree Committee he was responsible for locating and nominating 65 of Michigan's 75 National Champion Trees. Listing all of Mr. Thompson's accomplishments would consume all of the rest of the space in this article! Probably most impressive was his influence in the establishment of Sleeping Bear Dunes as a National Lakeshore, and setting aside Porcupine Mountains State Park as a wilderness area. For this he should be revered evermore. His successor, Woody Ehrle of Western Michigan University, is dedicated to furthering Mr. Big Tree's legacy.

caring for our trees

Ann Arbor's Forestry Division has one of the most respected programs in the country. We have a greater number of trees than most communities, and much more emphasis is placed, here, upon caring for them. Most cities have been regarding their trees as an expendable luxury. At last there's a growing awareness of how vitally important the plants are in the scheme of things. The key, of course, is economic feasability. Here in this town we have been soundly blessed with both the ways and means.

Elizabeth Dean, who died in 1964, designated the trees of Ann Arbor as the beneficiaries of her estate. Two million dollars were set aside, and today the interest off the principal funds a special tree-care research program. This is a unique endowment, one which continues to make a tangible difference in the state of the land in these parts. They should name forests and elementary schools after this woman. Her spirit deserves our gratitude.

Ann Arbor's laws are friendly towards trees. There are ordinances to protect the oldest and largest trees from destruction by "developers," a strain of business people who seem to feel that it is important for them to squeeze as many people into Washtenaw County as they can, and as quickly as possible. We see a small number of impressive landmark trees carefully left standing in order to enhance the property value of pricey condominiums, which occupy former wilderness areas. Herons are displaced from off the wetlands. Manicured lawns, no frogs. This is the future if we so aflow.

The air in this city is going to get nasty in a few years if we keep attracting more people who tear around in vehicles propelled by internal combustión engines. Plants, with their natural process of exchanging carbon dioxide for oxygen, are doing their part to keep it clean. Car exhaust and road salt are what we give trees to work with. As I choke on the fumes from rush hour trafile, I marvel at how a Silver Maple could grow to a height of 70 feet, a Champion in spite of the smog. Air pollution threatens all who breathe, and I love to bitch about it. Paul Bairley speaks much more diplomatically about these issues than I do, and he's extremely realistic about the nature of the ground surface within the city limits; not much of the original landscape remains, and we must work with care to handIe our turf properly. New ideas are changing the way things are done:

"Not long ago, the engineers would pack the soil around and under trees in the sidewalk or near the street to a 5% pour space. Now if you were into horticulture, you'd want a 5% pour space for storage of water and proper root development. Five percent pour space, that's dirt! That's not soil any more! They used to put a $100 tree in a $5 hole; now we put a $400 tree in a $50 or $100 hole." Over the past ten years, much better sense has been applied to this entire issue. Large planters are constructed, with ampie mounds of rich soil, so that the trees may thrive and hopefully outlive us.

a natural disaster

Trees are a beautiful combination of resiliency and rigidity. For tree lovers, the recent ice storm which swept through Southeastern Michigan with deadly force on the night of March 13 was a major and somewhat tragic event. The Forestry Di-

(SEE NEXT PAGE)

Giants Among Us

(FROM PREVIOUS PAGE)

vision staff, even as they work twelve hour days on behalf of the damaged trees, find it quite depressing. The clinging ice put about five times the normal weight on the tree limbs, and then the temperature dropped, causing the ice to remain on the trees for more than two days. This caused plenty more damage long after the storm had subsided.

Naturally there are individual trees with which a forester becomes well-acquainted. Painful to see a favorite tree maimed or knocked over; it is a humbling experience. The people I spoke with at the Forestry Division had obviously been working extended overtime doing something which means a great deal to them.

Once the cleanup is accomplished - all of the fallen branches chipped and trucked away for mulching - the department can get on with its regularly scheduled Spring planting; approximately 600 average-sized trees are introduced annually, with nearly 200 larger specimens set in less-developed areas. It is good to realize that this is a constant process. Presently, Ann Arbor has some 50,000 trees on 300 miles of streets, averaging 53 trees per mile. That's a pretty good density! For this reason they are able to concentrate on placing new trees near the expressways, and along all of the major thoroughfares.

As Paul talked of these exacting realities, it was clear that his department is constantly planning and reevaluating. This kind of intelligent management took many years to become standard proceedure. Like municipal recycling, it's the kind of thing we only fantasized about during the early 1970s. How good it is to see it really being done, and done so well.

looking for the oak savannah

"One of the New World lexical oddities Englishmen felt obliged to comment on was cleared, as applied to land formerly covered with trees. The American delight in cleared land amazed the 18th-Century Englishman, accustomed to cherish his forests and mock the comparative treelessness of Scotland... "

-H.L. Mencken

David Bornemann sat in his little office on the second floor of the old wood frame dwelling which houses the Leslie Science Center on Traver Road. Downstairs in the living room, a group of kindergarteners were being given a lesson in Natural History . Upstairs, David and I were concentrating on the state of Ann Arbor's land 160 years ago. He read aloud from "A Speculator's Diary" written in 1836 by John M. Gordon:

Journal entry, Oct 8th

We arose at five and stopped here to breakfast. I slept last night in on open garrett under a crack and awoke with a stiff neck. Cloudy. We've had bad roads again, and passed through a region heavily timbered, with frequent clearings . . . oaks with a cumference of nine to fifteen feet abound in the forest ... some of the largest I have ever seen . . .

The enthusiastic light in David's eyes intensifies as he reacts to the journal : "So he' s recording trees that were to fifteen-feet in circumference - that's like to five feet in diameter! I think that's our heritage: An Oak Savannah. To have those big, wide trees out in the sun, not in a dense forest where the trees grow tall and skinny because they have to reach for the sun way up top there. This was typical for Ann Arbor and even the name ' Arbor' refers to a more open grove type of setting; landscapes with prairie grasses underneath the big wide oaks scattered around . . .

"Our ancestors came over here and settled this wilderness area," he continues. "They wanted to make it more hospitable and they changed the landscape, draining the marshes (for which Michigan was well-known - malaria was a problem), dropping the water Ievel by about six feet. Along the way they stopped all of the fires that used to move through the area. This impacted the many species of plants which used to come up after the burnings.

"And, too, they introduced all of these plants that reminded them of their homes in Europe, of their grandmothers, and which they knew how to care for. They tried to turn this area into what they liked; a rural countryside." All of this altering of natural processes has completely changed the landscape, and the indigenous plants are being crowded out by what are termed "invasive species."

Consider the rapidly encroaching Purple Loosestrife, which resembles the liatris you'd get from your florist. These admittedly pretty stalks have taken over bogs, wetlands and even small bodies of water with alarming rapidity. Among trees there's the Norway Maple, which David says is "terribly invasive. Bird Hills Park is blanketed with young maples springing up everywhere. The ground is plastered with wet maple leaves so dense that nothing else can come up." The shrubbery problem is also chronic, with European Buckthorns seriously horning in where other trees would like to raise their young.

We're talking about the Big Trees of Tomorrow. If there's nowhere for the little saplings to take hold, they cannot establish themselves; few indigenous Champions, or none at all, will tower over the heads of the people who will live here a century from now. It's about looking back, looking ahead, and looking very carefully at what is happening right in front of us.

David Borneman feels obligated to act. "To do nothing," he says, "is still to make a choice ...." This is why he and his team of volunteers are opting for controlled brush fires in order to re-establish the pre-settlement ecosystem wherever possible, on behalf of the indigenous species. Most of us who glimpse the smoke rising from these scientifically conducted scorchings probably aren't aware that what is being done will benefit the Big Trees.

David's civic outlook: "A lot of what we do in natural area preservation is try and get people back in touch with our local nature, be that in a city park orin their own backyards, and to be good stewards of that. The Big Trees are a way for folks to feel proud of their neighborhood. A Big Tree can give you a deep, warm feeling inside. But one shouldn't lose sight of the forest for the trees. One big tree does not make a forest . . . There's an abundance of other life which exists in there."

My own favorite part of the forest is the lichen. Breaking the rocks down into soil, and covering the trunks of the trees which grow in that soil. Lichen is the Big Tree of the microscopic world. It's the fundament. That's where it all really begins. I said as much to David, who smiled and nodded his head. Outside, the kindergarteners were marching into the woods, holding hands and singing.

developing a relationship

David Eric Speiser, gardener, landscaper, logger and mountain man, began his brief interview with me by reading aloud this quote from "The Island Within" written by Richard Nelson, who lived for a long while among the Koyukon people of Alaska:

According to Koyukon teachers, the tree I lean against feels me, hears what l say about it, and engages me in a moral reciprocity based on responsible use. In their tradition, the forest is both a provider and a community of spiritually empowered beings. There is no emptiness in the forest, no unwatched solitude, no wilderness where a person moves outside moral judgement and law.

Citizen Speiser paged through the Big Tree Registry, and was obviously moved by the inclusion of an 84-foot American Basswood on West Huron: "The Basswood does really well in urban environments. But it's also just a great tree. Like, of everything on this list I have the best relationship with the Basswood. The inner bark is very fibrous, and you can make rope out of it. When I was working on the logging crew, if your chainsaw was really dull, because of the fibrous nature of the tree you couldn' t cut through it at all. lts flowers make the nicest honey; really delicate, nice honey. It's just a great tree.

"Susun Weed (a nationally acclaimed herbalist) says that you learn way more if you take just a handful of plants that you feel an affiliation with, and develop a relationship with them, rather than try and get to know a whole bunch of plants all at once. And that's the way I feel about this tree project. There's certain kinds of trees that I have a relationship with, because of my experience in life or what I am drawn to ... they have characteristics and personalities. It takes a long time to get intimate with them. "And you can't know all of them."

a love supreme

A tree ascended there.

O pure transcendence!

-Rainer Maria Rilke

Up on a sandy slope in the Arbor Hills region of our town, lives Betty with her birds in a beautiful house surrounded by a small arboretum, including three listed Champions. The spring rains had woken up her yard; mosses, grasses and buds were standing up with droplets clinging, and birds were improvising in the branches of the trees.

Betty is a tree lady. "I really like trees; other peoples' trees, little trees, sick trees, dead trees . . ." She knows each member of her menagerie quite intimately, and spoke casually but distinctly about their histories and special qualities. I covered a lot of ground, trotting after her with my tape recorder. Regarding how she cares for a Japanese bonsai Juniper which was given her in 1962, she simply said "All I do is whatever it wants."

BETTY'S TREES:

Yellow Birch: Champion - 30 feet tall. Native to Michigan but doesn't usually grow around here. It peels like a Paper Birch, and the sun shining "from the East or the West" illuminates the golden curls of bark.

Weeping Cherry (Birch): Champion - 28 feet tall. She called it "the grandfather." This unusual looking individual had a gnarled base, and she explained that the Japanese Birch was grafted onto a regular Cherry Tree. A dry spell about six years ago wiped out many of these in Ann Arbor. Betty's son, who is an accomplished landscaper and tree grower, told her to leave the sprinkler on it for three days, which she did, and it survived. Apparently the graft makes it difficult for water to get up to the branches. This one blooms the earliest of all the trees in her yard.

Cherry (or Paper) Bark Maple: Champion - 27 feet tall. Quite unusual as there are just a handful hereabouts. The bark, which later on will curl itself up, has a glowing, ruddy red appearance. Between the vertical trunks there are pockets which hold water; the birds and squirrels drink here during the summer. I saw ants round the rim of the hole. Spring is here.

White Pine: "This is my favorite tree back here. I've thought a lot about this, because I'm not going to stay here forever, and I'm not sure how I could get along without trees. This is one of the greatest trees I've ever known . . .." She points to a window overlooking the Pine grove. "My desk is right in there. Winter and Summer, this is where the action is. Other than the mail. Because the animals and the birds are here all of the time. It's a landing place and a take-off place .... Now, the needles of the White Pine have an unevenness that you can feel but you can't see. But when the wind blows and the sun shines on it, there's a silvery twinkle, and it's because of that unevenness. The needles pass in front of each other and behind each other. It sparkles .... You know they came here and cut down White Pines all over the State of Michigan, to make houses; they didn't think there was any end to it. And most of them were taken out for their straight wood; they just take out the heart and leave the rest. But these really grow well here. People shouldn't try and bring in things that don't grow here, when you have something that gorgeous that does like it here. There's no greater thing than a Michigan White Pine."

Michigan Wild Black Cherry: If it weren't for tent caterpillars, Michigan would still be covered with Wild Cherries. A great rejuvenator, lots of healing properties, used for medicine. This tough tree, if cut back, sprouts new branches with great vigor.

Eastern Red Cedar "What the deer live on, if they can find it."

Aspen: Grows most anywhere, under nearly any conditions. "I brought these back from the park in paper cups." Especially lovely "when they're covered with frost, in the sun, early in the morning, in a kind of fog, it's really a treat. When it really gets cold, below zero, the bark is apt to pop. So the farmers up North cali it 'popple.' New Englanders cali it 'Shakin Asp.'" (Additionally, the Indians referred to the month of December as "The Moon of the Popping Trees.")

Betty showed me the certificates she's been given, both for having Champions on her land and for nominating Champions elsewhere. When I asked her how it felt to live in the shade of such healthy specimens, she shrugged and said: "Those are the Big Boys. I don't really care anything about 'em being Champions; it doesn't mean anything to me."

"What do they mean to you?"

"I just love any trees."

suggested reading:

MICHIGAN TREES by Burton V. Barnes and Warren H. Wagner, Jr. 1981 University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

AGENDA wishes to thank photographers David and Peter Smith, as well as their staff camerawoman Yasmin Etemadi for helping us to properly portray the Big Oaks; the unsung Champion in Wurster Park, and the tree which is pictured on our cover; it grows on South University, next to the Clements Library.