The Digs At The Cobblestone Farm

The Digs at the Cobblestone Farm

By Eleanor Gerstenberger

News Staff Reporter

An archaeological “dig” right in our own backyard.

No solving of the mysteries of ancient civilizations here. No, none of that, but , instead putting together the pieces of a puzzle — the puzzle of locating the six outbuildings at the Cobblestone Farm on Packard Road.

While the farmhouse still stands, the shape, size and orientation — or how the building stood vis a vis each other — were somewhat of a mystery. The icehouse, smokehouse, carriage house, chicken coop, corncrib and small house barn had almost entirely disappeared.

And if the Cobblestone Farm Association’s plans to reconstruct some or all of these buildings are to be meaningful, they had to know first of all those details about the originals, explains Nan Hodges. She is a member of the Association’s Board of directors and is also in charge of the historical research, including the “dig ,” at the Farm.

A year ago, Assoc. Prof. Henry T. Wright of the U-M Museum of Anthropology faculty did a preliminary two-day study of the Cobblestone Farm site which determined that remains of the outbuildings were, in fact, present. His findings in July 1974 indicate that “dig ” could turn up more information about them.

So Michael E Whalen, archaeologist From the U-M Museum of Anthropology, And a volunteer crew of students from U-M, Community High School, Huron High School and Earthworks set out for two weeks in June to search for old foundations and artifacts.

“We were short of time,” Whalen says, “because that was all the money they had and all the time I had. But the site was the easiest one I've ever worked on. In some places you could actually see the foundation above-ground.”

Both sides of archaeological “digs” have been covered over the years, sometimes centuries, with anywhere from 2 to 5 meters of “overburden.” that's archaeologese for the dirt that has slowly worked its way over a formerly inhabited place. But the outbuilding foundations at Cobblestone Farm , he points out, were found under only a few inches of soil.

There was still digging involved, a slow careful digging through the soil which had accumulated over the site since the Farm’s decline following a devastating fire in 1924.

Archaeologists use a variety of tools ranging from a large digging pick to a small dental pick, he says. “it depends on what you want to find.

“You can dig quickly to remove the overburden by using a regular pick and shovel. Then when you get down to where you think the walls, foundations or other artifacts are, you work more carefully.

“Then you go at it with a six-inch bricklayers trowel. You can use the point for digging and the edge for scraping away the soil .”

Soil color differences often mark the places where buildings have stood in former times — dark soil inside from decay wood, etc, lighter soil outside the building's Boundaries where exposure to the sun has dried out the soil.

“But to see that color difference,” he notes, “you have to scrape the ground surface flat and clean. If it's rough and dusty, you can't see the color difference.”

An archaeologist's tool-kit also contains a whisk broom and small paint brushes , to gently remove soil from artifacts ranging from broken China (a lot of old broken China was found at the Farm ) literal to skeletons ( there weren't any).

A line level can come in handy if you want to find out how deeply you've dug. You just hang it on a string over the excavation and measure the length of the string down to the bottom.

“But you don't just dig things up,” he explains, “you also have to record carefully where each artifact was found so later, when you want to analyze the material it will be meaningful.

“At the Farm we used a metric grid of 1 meter squares to provide basic excavation units. The baseline of the grid was a magnetic north/south line which pass through the iron well head located just to the south of the horse barn. Excavation units were laid out to the east and west of the baseline.

“That way we know exactly what meter square something came from on the site.”

And so they kept track of the artifacts: glass, China, bone “probably from the Sunday pot roast ,” Whalen says ), buttons, and Arrowhead, buckles, a knife handle, window glass, nuts, bolts, screws , farm machinery parts, miscellaneous metal parts, thick blueish- green bottles, lamps, a 1919 Lincoln – head penny, an 1894 Liberty - head dime , electrical equipment and several pieces of kaolin clay pipe.

“These pipes were very frequently traded to the Indians of the eastern and northern United States during the 18th and early 19th centuries, “ Whalen says camel “and the Cobblestone Farm pipes possibly represent an early occupation of the site .”

By far, however, the most commonly found artifacts — and you wouldn't necessarily think of them as highfalutin “artifacts” — were the 5000 nails.

Those nails figured prominently in archaeologist Whalen's analysis.

“generally speaking it seems that relative age is an quantity of later use, with its implied modification an repair, may be roughly assigned to the Cobblestone Farm buildings by considering the ratio of large, (earlier ) to large, round (later) nails recovered from each building.

“this suggests that the icehouse is somewhat older or less prepared than, say the carriage house where the ratio is about 4 to 1. The ratio in the smokehouse is about 6 to 1, suggesting that this building may have survived longer than the icehouse .”

Not all the buildings were investigated in equal detail because of the pressures of time, although our precisely located in a map. The approximate floor area of each structure was also determined.

Here , very briefly , is what Whalen and his crew found:

— the ice house was about three by three meters. “the building had disintegrate it to such a point that no construction details were evident. The back (East) wall suggests that the foundation consisted of a double line of stones, each some 25 to 45 centimeters across .”

— The carriage house, 14 by 6 meters, was the largest building excavated. “three corners and two complete size of the carriage house were recovered ,” he says, “so that the orientation in the measurements are acceptably accurate.

“Like the other buildings, this had suffered extensively from stone looting, along the foundation line was very clearly defined by small rock and brick rubble.”

— the chicken coop, a small, frame-building, probably stood on stone supports and was about 3.2 meters by 4 meters. “The West End of the building was quite well preserved, but the East End was unfortunately almost entirely destroyed or removed.

“Domestic glass in the forms of bottles, jars, glasses and lamps were quite common here and this area was also the source of the largest single collection of China made at the site. It would thus seem that the kitchen coop also served as a dump for domestic trash, as there is no reason to suspect that fine glass in China were associated with any of the original functions of the building.

— “Melted glass slag were also found, seeming to represent deliberate melting rather than accidental fire damage, (as in the carriage house) as much of the glass covered was reduced to long drips or round blobs. Glass- working somewhere in the carriage house – chicken coop area is suggested.”

— The horse barn measured 7.3 by 6.7 meters. “it was the least excavated building in this season's work,” Whalen says, “due in part to practical consideration, but largely because much of the original stone foundation was visible above the ground level.”

— The corn crib was the most difficult to locate because of its construction techniques. “the building was built on brick and stone piles rather than on a continuous stone foundation (probably to keep out rodents) so that minimal traces were left on the ground.

“Nevertheless, remnants of three of the pilings , include the southeast corner of the building , relocated and soil color differences which may mark the Southwest end of the structure were also observed. The approximate size of the corn crib was 7 to 8 meters by 7 to 8 meters although the building wasn't necessarily square.”

All of this archaeological data, Whalen point out, “should provide a reasonably complete picture of this part of the Cobblestone Farm.”

“It was important to our overall planning,” Hodges says.

“That way we can select those to reconstruct which will serve a dual purpose — education and storage or a caretaker's office. That's unless a philanthropist comes along who wants to help us reconstruct all of them.”

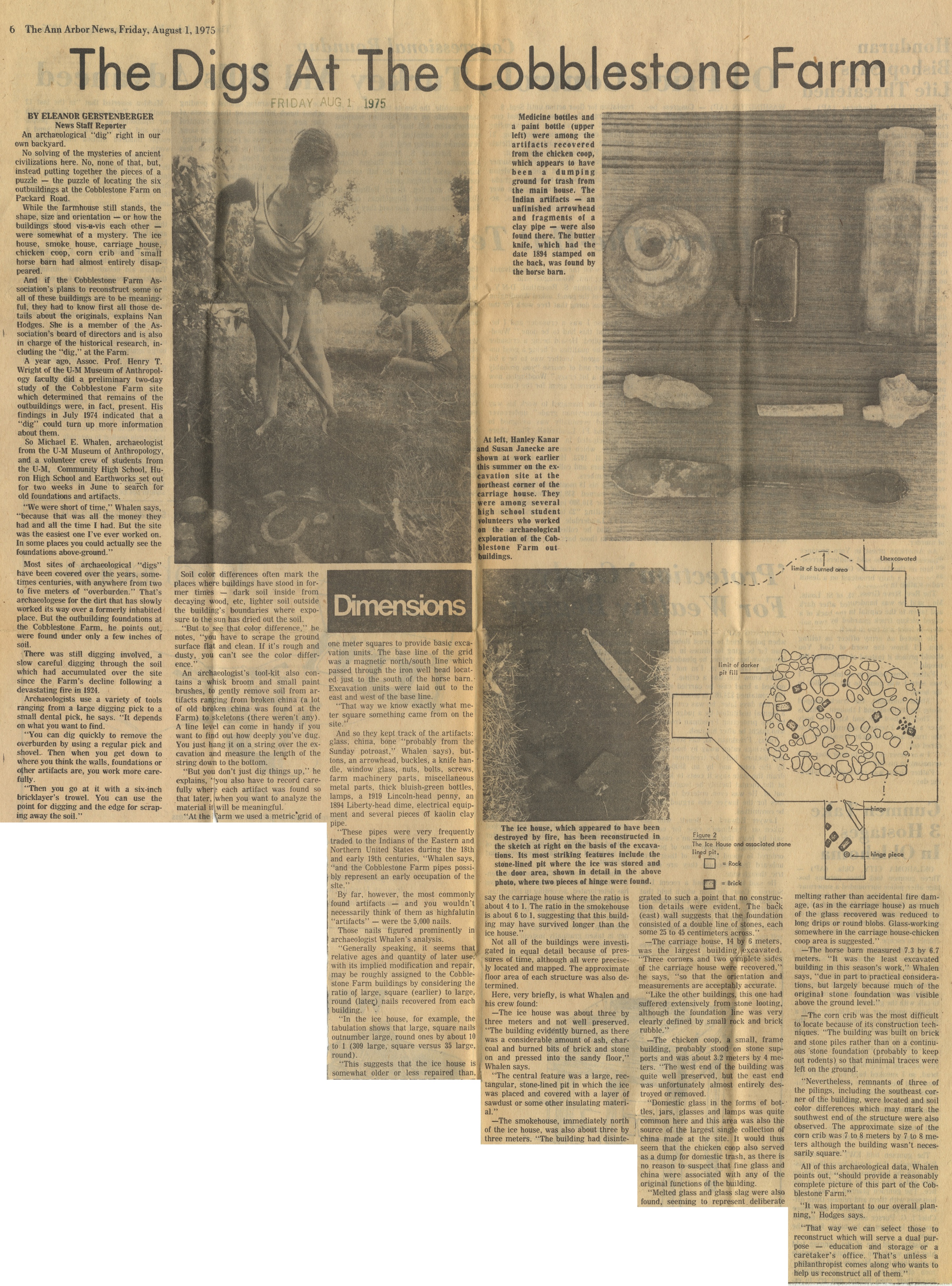

At left, Hanley Kanar and Susan Janecke are shown at work earlier this summer on the excavation site at the northeast corner of the carriage house. They were among several high school student volunteers who worked on the archaeological exploration of the Cobblestone Farm outbuildings.

The ice house, which appeared to have been destroyed by fire, has been reconstructed in the sketch at the right on the basis of the excavations. Its most striking features include the stone- lined pet where the ice was stored and the door area, shown in detail in the above photo, where two pieces of hinge were found.

Article

Subjects

Eleanor Gerstenberger

University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology

Ticknor-Campbell House

National Register of Historic Buildings & Places

Museums

Huron High School - Students

Historic Buildings

Farms & Farming

Earthworks High School

Cobblestone Farm Committee

Cobblestone Farm

Buhr Park

Benajah Ticknor Farm

Community High School

Has Photo

Old News

Ann Arbor News

Nelson Booth

Nan Hodges

Michael E. Whalen

Henry T. Wright

George Campbell

Ezra Maynard

Benajah Ticknor

2781 Packard Rd