The M.U.G. (Michigan Union Grill) in the 1950s-1960s

Although an affluent community like Ann Arbor was hardly the culture in which ‘The Beat’ movement (theoretically) thrived and was designed for, nonetheless the influence of ‘The Beats’ was present and very much felt in Ann Arbor back in the late 1950s and the early 1960s, student poets and hanging out.

More on Ann Arbor in the 1960s

I am happy to share with you some wonderful reminisces on Ann Arbor in the 1960s back in the day by my friend Paul Bernstein.

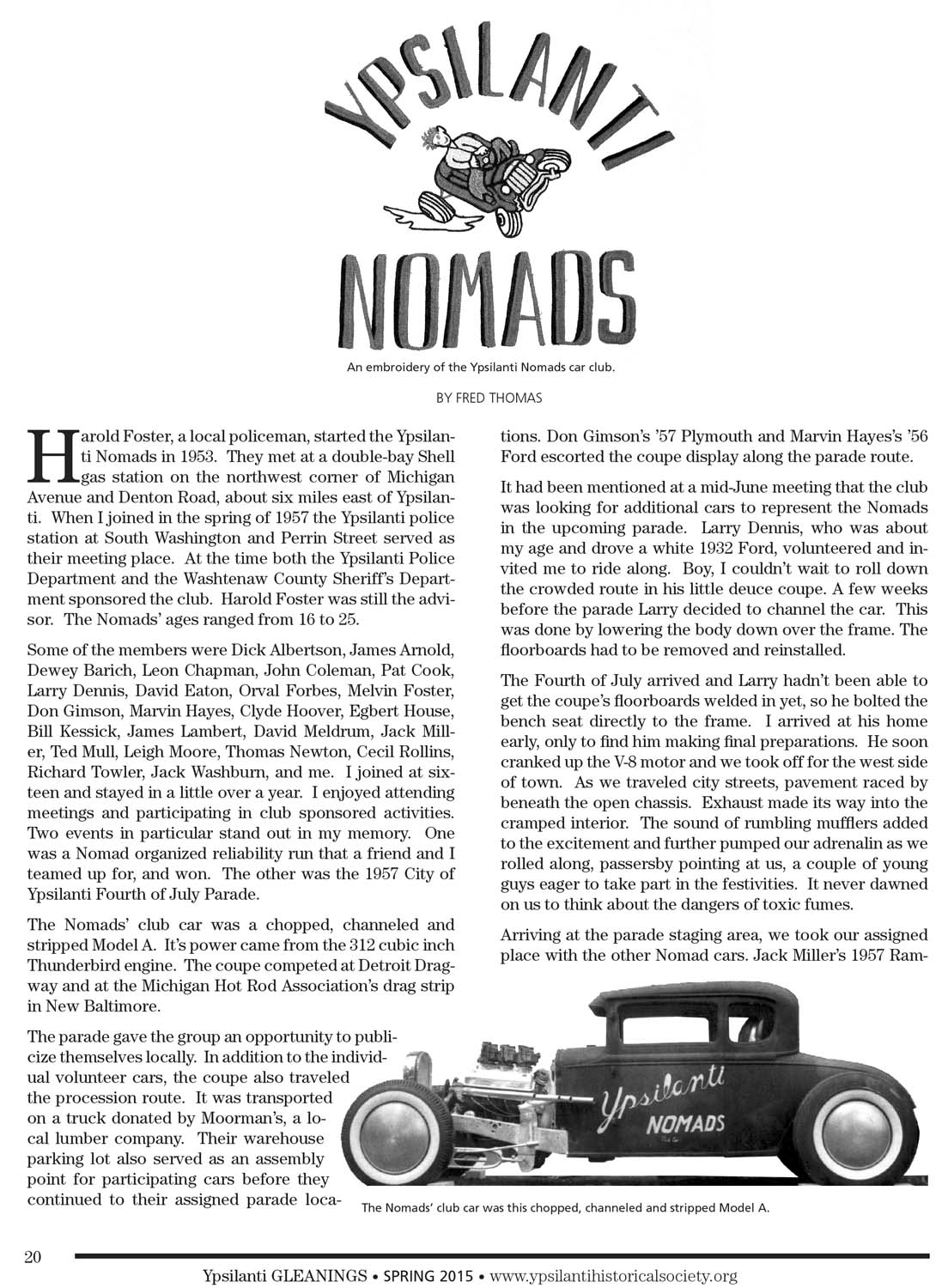

1960s: Ann Arbor's Gay Bars

Back in the 1960s, as to where I spent the most time, outside of the bars our band played music in, it was

The Forgotten Jazz Scene

How could the repeal of prohibition in 1933 affect the onset of The Sixties in Ann Arbor? It sounds like Chaos Theory, where the flapping of a butterfly wing in Brazil affects the amount of snow that falls in Greenland. But such an effect did occur. And the sad thing is that the scene I am about to describe is hardly remembered. I keep waiting for someone to write about it, but it might have to be me!

The Washtenaw Alano Club

Since 1969, the Washtenaw Alano Club (WAC) has fulfilled its mission “to provide a facility and environment conducive to spiritual growth for recovery from addictive behavior” by hosting a variety of 12-step recovery groups and offering social, educational, and recreational activities.

WAC currently serves 1,500 visitors each week over the course of 72 meetings covering eighteen distinct 12-step programs. Among these are: Al-Alanon, ACOA, AlaTeen, Narcotics Anonymous, Sexaholics Anonymous, Gamblers Anonymous, and Artists Recovering Through the Twelve Steps.

History & Founders

WAC was founded in 1969 through the efforts of a group of people in recovery who decided Ann Arbor needed its own Alano Club. WAC is currently one of numerous Clubs nationwide that host regular meetings and other social events for people in recovery. Some of the early community leaders and members who played a role in establishing WAC are: Leo H. Evans, Grace J. Yesley, Allen L. Rendel, Richard Hammerstein, Judge Sandy J. Elden, James H. Fondren, Rev. Robert C. Grigereit, Ronald D. Rinker, Dr. Margaret Clay, Mrs. Robert Harris, James W. Henderson, Dr. Russell F. Smith, Patricia O'Sullivan, Gerald H. Voice, Ed L. Clark, Margaret E. Brooks, Patricia Goulet, Paul Clark, Elaine Ambrose, Barry Kistner, Steve Carr, and Dr. George S. Fischmann.

WAC filed articles of incorporation on October 27, 1969, and first began meeting at an older house on North Main Street. However, this location's cramped quarters and lack of parking weren't ideal and by March 1970, business meetings were being held once a month at the Calvary Methodist Church at 1415 Miller Avenue. On July 1, 1971, the Club drafted its first By-Laws, and on April 6, 1973, WAC was officially granted 501(c)(3) non-profit status. Meanwhile, original charter member, Leo H. Evans, initiated fundraising efforts to find a more suitable meeting space and in September 1975, WAC signed a lease for its first home in the Fourth Avenue Arcade at 212 South Fourth Avenue in downtown Ann Arbor. They moved in on November 23.

After three years, the reputation of this particular block of Fourth Avenue, which at the time included both liquor stores and adult bookstores, encouraged the group to begin scouting for a new location. For a short period, beginning in August 1978, this location would be an office building at 2500 Packard Rd, Suite 204; then, on November 4, 1980, WAC moved to 2761 South State Street. During the seven years at the State Street location, the Club expanded services to include additional activities and social events such as volleyball and softball teams.

995 North Maple Road

Late in the summer of 1986, WAC was notified its lease would not be renewed and the State Street building would be sold. With only 60 days to vacate, members scrambled to find a new location. At this time, they learned that the Ann Arbor Public School Board was selling property at 995 North Maple Road - the former Fritz School building - which had served as both an elementary school and alternative school within the Ann Arbor Public School system. Although WAC was not the highest bidder for the property, it was granted the bid of $127,500, due in part to members on the School Board who supported the Club’s mission to serve the community. The Ann Arbor City Council also approved a rezoning request to permit WAC to use the building.

WAC now owns the building at 995 North Maple. Set on a large parcel of oak woods with picnic areas, parking, and a rain garden, its interior space consists of meeting rooms, a lounge, and a concession area. Its first major project was to build a parking lot, and a 1992 fundraising drive helped to replace the aging roof. The work of several Board committees has contributed to other improvements to both interior and exterior spaces over the years.

On May 21, 2013, as part of an effort to rebrand the Club and fulfill a strategic plan to attract more members, the Board of Directors revised Club bylaws to cancel the collection of member dues and changed the name of the Club to Maple Rock. But these efforts were not universally embraced and were challenged by some long-time members. In December of 2015, county judge Archie Brown ruled that the Club was indeed a Membership Non-Profit and, in February 2016, authorized an election to choose new Board members. The Club's name also reverted to the Washtenaw Alano Club.

Events & Activities

Over the course of its history, WAC has sponsored numerous events and fundraisers, including monthly dances held at off-site locations such as Saint Francis of Assisi Church on East Stadium Boulevard. Other annual events include picnics, Christmas tree sales, and free holiday meals. Social activities include potlucks, movie nights, games nights, and sports.

Learn More about the Washtenaw Alano Club:

Articles from the Ann Arbor News

Photographs from the Ann Arbor News

Washtenaw Alano Club's 50th Anniversary Video

Highlights from oral history interviews with Mark, Jess, Kathy, and Nan

Library Threads

For nearly two centuries, volunteers and professionals have connected local readers to a wider world.

From its earliest days Ann Arbor has been a reading town with enthusiastic library supporters. Its first library was launched in 1827, just threeyears after the ci!J was founded. Even so, the history of our libraries is not a straight line from then to now. Different threads, professional and volunteer, paid and free, have woven back and forth ever since.

Today those strands are woven tightly together: we now have the professional Ann Arbor District Library and two independent volunteer groups that work closely with it. The Friends of the Library turns sixty-three this year, and the Ladies Library Association celebrates its sesquicentennial this month -- jointly with the AADL, which is marking its own twentieth year of independence (see Events, October 1).

We know about the 1827 library because in 1830, George Corselius ran an article lamenting its deficiencies. The editor of the Western Emigrant sought "twenty or thirty individuals" able to pay $3 each to expand that small collection into a more robust "circulating library." For that fee, readers could read Fanny Trollope's Domestic Manners of the Americans or the Encyclopedia Americana. Other private libraries followed, as well as reading clubs whose members bought books to share.

It wasn't until 1856 that the city had its first free, publicly accessible library. When the Union High School opened that year at the comer of State and Huron, citizens could use the library in the superintendent's office.

In 1866 the Ladies Library Association was formed as a subscription library. According to the group's history, the thirty-five founders -- "a determined group of socially prominent local women" -- paid $3 to join and $1 a year in dues for the privilege of borrowing books from its collection. They also sponsored lectures, concerts, art shows, and readings.

After renting various places, in 1885 the LLA bought a lot at 324 E. Huron. The club hired Chicago architects Allen and Irving Pond -- whose mother, Mary, was a member of the LLA -- to design the city's first freestanding library there.

Four years later, in 1889, the school board moved the high school library into its own room, and hired twenty-three-year-old typist Nellie Loving as the district's first librarian. She stayed for thirty-nine years and was an energetic advocate. "She even went to the firemen at the station," recalled Elizabeth Stack, a founder of the Friends of the Library. "They were just sitting around. 'Why don't you read something?' she asked." She followed up by bringing them books, which they later returned asking for something "livelier."

Loving's response is not on record, but the ladies of the LLA didn't just want to entertain readers-they saw themselves as "a force for intellectual and moral improvement." The minutes of the group's 1872 annual meeting observe that though the demand for fiction exceeded the supply, "we are happy to state that a large proportion of the books purchased during the year are of a character to stimulate earnest thought and fully meet the needs of the intellectual mind."

From its start, the LLA women wanted a free public library -- but they couldn't get the city to fund it. Finally, in 1902, LLA president and school board member Anna Botsford Bach suggested that the two groups apply jointly for a $20,000 grant from Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate who was building libraries all across America. However, they deadlocked over the location: the school board insisted that the library be in or near the high school, while the LLA wanted a separate site.

The problem was solved two years later, but at a high cost: in 1904, the high school burned down. Luckily students rescued most of the 8,000 books in the middle of the night; they were stored across the street in the Methodist Church's parlor.

The school board applied for and won a new $30,000 Carnegie grant. The library was built alongside and connected to the new high school, but the school faced State St. and had a skin of brick, while the library faced Huron and was finished in stone.

In 1916, on its fiftieth anniversary, the LLA gave its collection of several thousand books to the public library, and its building to the school board. The building was used by the Red Cross in World War I, and later by the Boy Scouts. It was tom down in 1945; its site is now occupied by the fortress-like Michigan Bell building.

In 1928, Nellie Loving's successor, Frances Hannum, separated the school and public collections. She moved the schoolbooks to the third floor and made the bottom two floors a public library, with the lower level the children's room.

In 1953, the city sold the high school to the U-M, using the money to start work on what is now Pioneer High. The university renamed the old school the Frieze Building, after a beloved classics professor. When it was tom down in 2007 to make way for North Quad, the library's Huron St. face was incorporated into the wall of the quad-what preservationists call a facadectomy.

The school's move again brought up the question of where the public library belonged. The Friends of the Library was organized in 1953 to lobby for a downtown site: the comer of Fifth and William, where the old Beal house was for sale. Elizabeth Stack organized the Friends' first fundraising book sale on the grounds of the house. Friends member Bob Iglehart recalled in

The Ladies Library Association built its own "circulating library" on Huron in 1885. a 1995 remembrance that "it was a rather pitiful affair, not a whole lot of books, but there were also homemade cookies, potted plants, and the general aspect of a ladies church affair." And it raised enough money to rent a bookmobile to take books to playgrounds that summer.

The schools did buy the site, and the new library, designed by Midland modernist Alden Dow, was dedicated on October 13, 1957. Clements Library director Howard Peckham said that the shared civic space "added an extra room to each of our houses." The Friends moved their growing collection of donated books out of Stack's garage and into the library's basement, and their sales to its sheltered front porch.

The new library was still run by the school system, so the Friends lobbied for a citizens' committee to advise the school board on the library's needs. Fred Mayer, a committee member in the 1960s, recalls that they dealt with such issues as fees for nonresidents, problem patrons, new programs, and summer reading.

Finances got easier after 1973, when the school board put a separate 1.3-mill tax for the library on the ballot. It got more votes than the schools millage, and in 1974, the library added a 20,000-square foot addition. Designed by architect and book lover Don Van Curler, its high wells of windows and enclosed garden fit with the original Dow design. In 1991 Osler/ Milling designed a second addition, adding two floors to the Van Curler addition, renovating the older part, and updating mechanical systems.

In 1980 the Friends expanded their annual sales into a bookshop in the library's basement. Elizabeth Ong, who organized it, is still an active volunteer. The shop was managed for many years by volunteer Mary Parsons, who stressed in her final report that "the sales should always be considered a community service first." But in addition to getting books into the hands of new readers, the sales also raised a lot of money. The Friends used to sponsor the "Booked for Lunch" speaker series and many other services and amenities such as literacy programs, staff workshops and scholarships, and taking books to hospitals and senior residences. They also advocated for the new branches and led millage campaigns.

In 1994, when the state's Proposal A took away school boards' authority to levy taxes for public libraries, the schools and city council sponsored creation of a new district library. An interim board was created, with Mayer as president, to divide the buildings and land, and reconfigure services that had been provided by the schools.

On June 10, 1996, voters in the Ann Arbor School District overwhelmingly approved a two-mill district library tax, and elected the first library board. Of the original seven members, only Ed Surovell remains today. Twenty years later, he says, "We're dramatically better, with higher attendance and a higher number of programs." He points to advances such as more foreign language books, the incorporation of the county library for the blind, and the construction of three new branches, Malletts Creek, Pittsfield, and Traverwood, plus the expansion of the Westgate branch.

As for the Internet, Josie Parker, director of the library since 2002, says, "We decided, instead of fighting it, to use it as a tool." Parker points out that "the public can now use the library's catalogue 2417 wherever they may be." Reserving or renewing books and getting books from other libraries are also much easier. The online Summer Game attracts 7,000-9,000 players, from children to adults.

Although Ann Arbor voters have a history of supporting library funding, in 2012 they turned down a millage to build a new downtown library. Since then, the AADL has been figuring out how to best use the present building, make necessary repairs, and, in Parker's words, "match the collection with the space." Fiction has been moved to the second floor and magazines and local history materials to the third floor. The first floor still has art prints, DVDs, and new and Zoom Lends books (high-demand volumes that rent for $1 a week), along with art, science and music tools. These are stored on wheeled carts, so a large area can be cleared for special events such as the Maker Faire and a comic book convention. A library board slate running in November (seep. 35) says they'll make a new millage vote a priority.

Like the library itself, the Friends now make greater use of the Internet. In Parsons' time, when they spotted valuable books or documents, they worked at either finding a place to donate them, perhaps to the Bentley or Clements, or sold them. The Internet has made this process much easier. (It helps that many of their sorters are retired librarians or specialists who are good at identifying books of interest.)

When the elevators failed during a routine inspection in 2014, the Friends bookstore moved up to the first floor. Business was so good there that they stayed. The group now annually gives the library $100,000 or more; the money is used mostly for children's activities, including library visits for every second grader in the district. The Friends' former basement space is now the AADL's "Secret Lab," where children can work on messier projects such as cooking or art.

The Ladies Library Association also is still active. One of its earlier members, Alice Wethey, "was a terrific treasurer," says Joan Innes, a member for sixty-three years. "She was a tremendous investor and put our money into blue chip stocks." The LLA's twenty-woman board, which includes both Innes and her artist daughter, Sarah, uses the income to support the library's purchase of art books, framed fine art reproductions that patrons can borrow, and art-themed games for the children's department. As the new branches opened, the LLA also bought original works by local artists to display there.

The library has just hired its own volunteer coordinator, Shoshana Hurand, formerly with the Arts Alliance. "It's a real breakthrough and will offer volunteers a wider variety of opportunities," says library board member Margaret Leary. Parker explains that until now library volunteers have been handled by whoever answered the phone for the specific project. Now one person will see where volunteers might fit-maybe with kids' sewing or art projects, or online help, or in many other ways. The Friends will stay totally separate, although both entities will probably send people to each other.

On October 1 (see Events), the Ann Arbor District Library and the Ladies Library Association will celebrate their twentieth and !50th anniversaries, respectively. The event will feature a talk by Francis Blouin, U-M professor of history and information and retired head of the Bentley Historical Library, entitled "Connecting the City."

"We talk a lot these days about 'connectivity' that now means being plugged into the Internet and all the information it provides," Blouin explains. "But being connected certainly predates the arrival of the smartphone. Ann Arbor in the nineteenth century, though a small town, also wanted to be connected to the wider world." Thanks to generations of avid readers and hardworking library supporters, those connections now are stronger than ever.

[Caption 1]: Founded in 1866 as a subscription library, the Ladies Library Association continues to support library purchases. Artist-member Sarah Innes envisioned an early meeting (left) and painted a group portrait today (below).

[Caption 2]: A $30,000 grant from Andrew Carnegie paid for the city's first dedicated public library. Only its facade survives, on North Quad.

[Caption 3]: The Ladies Library Association built its own "circulating library" on Huron in 1885.