Ann Arbor Takes Flight

In this day and age, when most townies head to Detroit Metro Airport to travel by commercial airplane, it's easy to overlook our own small airfield. In the 1920s--"The Golden Age of Aviation"--Ann Arbor Municipal Airport (ARB/KARB) was front page news. In October of 1928, many well-dressed men and women gathered together on the far edge of our town to celebrate this great achievement. Popping champagne would have been appropriate, if not for prohibition. This was a story of progress, a source of local pride, the scene of many ladies in cloche hats, and a few gentlemen sporting leather aviator caps with large earflaps.

1925 - A Flying Field?

With major advancements in aviation, many airports surfaced across the state of Michigan in the 1920s. On July 2, 1925, an Ann Arbor Times News editorial declared "A flying field, with all the modern conveniences for aviators, is being discussed unofficially in official circles of Ann Arbor...No community of any size will want to be without a landing place within a decade or less." The idea of a local airport was appealing, but ultimately went dormant for a year.

1926 - Steere's Farm Is Suitable

In July of 1926, the Ann Arbor Park Commission launched a serious push for a local airport, and turned their attention to nearly 300 acres in Pittsfield Township. Just south of Ann Arbor, stretched across State Street, this land was already owned by the city. Purchased by Ann Arbor's Water Commission around 1914, the property was farmland, with deep gravel springs supplying much of the city's drinking water. The property also had wetlands, offering the University of Michigan a wide variety of research materials, including venom from resident massasauga rattlesnakes. Formerly owned by retired professor Joseph Beal Steere, the land was still referred to as "Steere's Farm" and "Steere's Swamp". Hackley Butler, park commissioner, and Eli Gallup, park superintendent, collaborated on plans to obtain a portion of the Steere farm property as a site for the flying field. Professor Felix Pawlowski, University of Michigan Aeronautical Engineer, was consulted and gave his stamp of approval. Gallup described Steere's Farm as "lying high, with no obstructions...suitable for the landing of light or heavy planes".

1927 - Airport Site Is Approved

For another year, deliberation swirled around a potential landing field on the Steere's Farm land. Public sentiment toward a local airport shifted in the summer of 1927, when Charles Lindbergh's transatlantic flight made world history. Both of his parents were University of Michigan alumni, which added to the local interest. Ann Arbor residents, like the rest of the country, were suddenly enamored with aviation, and public interest in flying was high. A new airport was now deemed essential to maintain Ann Arbor's reputation as a prosperous, forward-moving municipality.

'AIRPORT SITE IS APPROVED' was a front page Ann Arbor Times News story on November 26, 1927. City aldermen supported using a portion of the Steere's Farm land, and would recommend transfer of the property from the water commission to the park commission. The Chamber of Commerce and City Council both approved the proposal, with assurance that no harm would result to the wells. In early December 1927, 115 acres of Steere's Farm were transferred between city departments. Ann Arbor City Engineer George H. Sandenburgh, immediately began designing an airfield.

January - April 1928, Leonard Flo & The Ann Arbor Flying Club

Lieutenant Leonard Stanley Flo was a city resident for less than five years, but is a permanent part of the Ann Arbor Airport's history. After graduating from U. S. Army Air Corps training in Texas, he served with the First Pursuit Group at Selfridge Field in Michigan. Flo flew as an air mail pilot in Florida, and was also a pilot for the Wise Birds Club in Detroit. He was living on the edge of West Park, near downtown Ann Arbor, as plans came together for a local airfield.

In January 1928, Lt. Flo submitted a letter to the city, proposing himself as manager of the new airport. He suggested a contract giving him responsibility of operating and maintaining the airfield, and allowing him to conduct a flying school on the property. He asked for no compensation from the city, as he would profit from his business, Flo Flying Services. As an experienced flyer, he had inspected the property and found it excellently located with natural advantages for flying facilities. City officials welcomed his proposal, and began drafting a formal agreement in March 1928.

March 1928 also saw the birth of the Ann Arbor Flying Club, a group of Ann Arbor men who joined together to help establish an airport. The list of charter members was essentially a "who's who" of Ann Arbor businessmen, with many joining simply for networking and the status of being involved in the up-and-coming world of aviation. With annual dues starting at $25, equivalent to over $400 a year in 2023, membership was limited to financially privileged citizens. Within a week of being formed, membership in the club jumped to over 100 individuals.

With support from Leonard Flo, and financial assistance from the Ann Arbor Flying Club, work on the new airfield progressed rapidly. By the middle of April 1928, work crews were busy rolling & leveling the land, and installing cinder drainage tiles.

May 19, 1928 - First Landing, 12:05 p.m.

"Fix the date in your mind, and keep it there, because some day you will want to "remember" the first ship at the first airport, an occasion that marked a progressive step by this community." - Ann Arbor Daily News, Editorial, May 19, 1928

In May 1928, Leonard Flo decided to attempt a flight from the Ford Airport in Dearborn onto the Steere Farm property. He hoped to prove to local citizens that a landing could be made on the prepared runway, even after the ground was soaked with several days of spring rain. The Ann Arbor Flying Club had put nearly $5,000 toward the airport project, and the landing was a success.

Accompanying him in a Waco biplane were Eli Gallup, park superintendent, and Harold 'Charlie' Ristine, local news reporter. Gallup was encouraged by the results, and planned for further improvements on the prepared runway, dragging/rolling/tiling a second runway, lighting, and construction of a hangar.

Despite the fact that it was probably really loud and cold in that biplane, Charlie Ristine published a glowing review of his flight in the Ann Arbor Daily News. An editorial lauding the achievement was also printed. A photographer captured photos of the event at the future airport, and the front page of the paper featured an image of the three men smiling and wearing leather aviator caps.

July 17, 1928 - Ann Arbor Airmail Service Inaugurated

Thompson Aeronautical Corporation (TAC), out of Cleveland, Ohio, was awarded one of the early Contract Air Mail routes (CAM 27) from the U.S. Post Office. CAM 27 connected cities from Chicago, Illinois, to Bay City, Michigan, with service starting July 17, 1928. On that date, postal authorities, the Ann Arbor Flying Club, Chamber of Commerce members, and several hundred excited spectators were on hand at the new airport to welcome TAC pilot Lester F. Bishop as he landed his plane in Ann Arbor and received a sack of more than 2,000 letters from Postmaster Ambrose C. Pack. Yet another complimentary editorial ran in the newspaper: "...the fact that the service has been extended to Ann Arbor should be a source of gratification for every resident. It is something to which he can "point with pride," as the saying goes."

October 9, 1928 - Ann Arbor's New Airport Is Dedicated

On a sunny morning in October 1928, three P-1 army first pursuit planes from Selfridge Field circled over Ann Arbor. Commanded by Col. Charles H. Danforth, they touched down on the runways near a crowd of over 350 people, commencing the dedication ceremony of the completed Ann Arbor Municipal Airport. They parked near a Ford Tri-motor (affectionately known as a Tin Goose), a Hamilton Metalplane, and two Spartan planes, which were the property of Flo Flying Services.

The invitation to the dedication, published in the newspaper, noted that all were invited, "including women". Flo Flying Services brought in visitors from surrounding towns by plane, while local residents made their way to the festivities down the rough gravel State Street. City and Washtenaw County officials, members of the Ann Arbor Flying Club, Exchange, Rotary, and Kiwanis clubs were all present. Noted guests included the president of the Hamilton Aircraft Company (owner of the aircraft parked outside), Ford Motor Company's advertising manager, the general manager of the Detroit-Cleveland airline, the assistant traffic manager of Thompson Aeronautical Corporation, and a handful of distinguished pilots. Michigan Governor Fred W. Green was invited, but unable to attend. Guests gathered in the new hangar for a noon luncheon program, which opened with an invocation by Rev. Allison Ray Heaps, pastor of Ann Arbor Congregational Church.

Mayor Edward Staebler addressed the crowd with "Plans for the Future", followed by "A Word from the Council" made by Alderman Herbert Slauson. Levi Wines spoke on "Keeping Abreast With the Times", and Jerome Sutherin, of the Thompson Aeronautical Corporation, spoke about Ann Arbor's airmail service. Shirley Smith, secretary and business manager of the University of Michigan, outlined the history of the new airport, including praise for Eli Gallup and Hackley Butler who had originally championed the idea of a local airfield. Beyond the boasting and self-praise, spectators were most thrilled after the luncheon, when masterful Selfridge Field pilots entertained with "air antics" over the airport.

See For Yourself: Historical Ann Arbor Airport Footage

Ann Arbor History - Aerial Footage of Ann Arbor in the early 1930s, an eight minute video narrated by Al Gallup (son of Eli Gallup), is available on YouTube. If you'd like a glimpse of Leonard Flo in action at the Ann Arbor Municipal Airport, be sure to give it a watch.

Genealogy

Looking For A Washtenaw County Obituary?

To request an obituary for the greater Ann Arbor area, email the Ann Arbor District Library Archives at archives@aadl.org. Staff will conduct a search and contact you with any results.

Ann Arbor Taxicab Co.'s Second Annual Banquet Program, January 11, 1916

The Story of the Walker Livery and Taxi Business

Foreward

Community High School

Community High School (CHS) is an alternative public high school serving grades 9-12 located at 401 North Division Street in Ann Arbor's historic Kerrytown District. It was one of the first magnet schools to arise from a nation-wide wave of experimental schools that drew on the social movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and was specifically influenced by social and political activism in Ann Arbor at the time.

History of the Pall-Gelman Dioxane Groundwater Contamination Cleanup

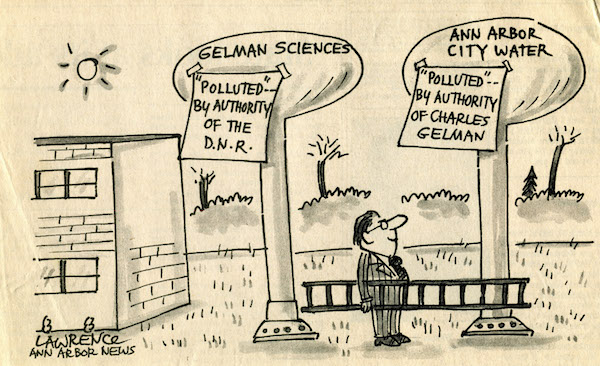

It could have been a quintessential success story about a young entrepreneur-scientist starting a hobby in the basement of his home and within 20 years turning it into a multi-million-dollar international business.

And it is that story – of how a University of Michigan graduate student named Charles Gelman in 1958 began working on a process to make micro-porous filters, used to detect air and water pollution, among other applications. He built his Gelman Sciences into one of the leading industries in the Ann Arbor area.

But over time the glowing business narrative instead became a history forever tainted by a chemical called 1,4-dioxane. A probable carcinogen once used in Gelman’s manufacturing process, dioxane polluted soil and groundwater at the company’s Scio Township plant, and it eventually spread into a large plume of underground contamination in northwest Ann Arbor.

Pollution problems at Gelman were first reported in 1968 and 1969, but there was surprisingly little regulatory action and sparse news coverage. Fifteen years later, in 1984, the word “dioxane” first appeared in news coverage. It was suspected in Third Sister Lake near Gelman and confirmed in nearby wells the following year. The cumulative effect of the slow-moving investigation and remediation grew more serious by the week, month, and year. Revelations included the fact that Gelman had sprayed tainted wastewater on its lawns as a way to get rid of it. Overflows and leaks at its two unlined storage lagoons contributed. State regulations were so weak that a judge at one point ruled in favor of Gelman’s contention that it had done nothing wrong. Yet dozens of homeowners were told to stop using their wells and were supplied with bottled water. Negotiations emerged over who would pay for connecting the affected residents to the Ann Arbor water system. In one of the more bizarre developments, Gelman employees went door to door, scheduling times and paying for residents to shower in a local hotel. Gelman and the state sued each other; residents sued Gelman; the legal wrangling was as slow as the progress monitoring and treating the pollution.

Millions of gallons of tainted groundwater have been extracted, treated, and re-injected into the ground. Dozens of test wells have been drilled in an attempt to track the spread of the contamination. The major concern, even still in 2016, is whether the underground plume will eventually migrate into Barton Pond on the Huron River, the major supplier of water for Ann Arbor.

It is a definition of irony: A major water pollution clean-up caused by a company that made filters to detect water pollution. This story of business success intertwined with environmental disaster is laid out in hundreds of Gelman-related articles published in The Ann Arbor News from the early 1960s until the newspaper closed in 2009. (Note: Gelman Sciences was sold to the Pall Corporation in 1997, so most news coverage now calls it the “Pall Corp. clean-up” even though dioxane use was discontinued while Gelman still owned the company. Also, Pall was acquired by the Danaher Corporation in 2015 though the Pall name was retained.)

The library’s completion of the Gelman digitization in early 2016 is a remarkable coincidence, coming only a few months into another major Michigan water contamination case – in Flint – that has focused national and international attention on public water supplies. The articles also provide valuable context as Ann Arbor public officials in early 2016 are making yet another push to find more funding to pay for the continued monitoring and clean-up of the dioxane.

The reader of this collective history is left pondering the degree to which the environmental damage and tens of millions of dollars in cleanup costs could have been reduced with more aggressive action when the pollution was first discovered. Many questions remain regarding the culpability of the company and why it wasn’t monitored more aggressively by local, state, and national agencies tasked with guarding public health and the environment.

Reading the reporting with the benefit of hindsight frequently proves maddening: How could society care so little about toxic waste being dumped directly into the environment? It shows that public opinion and regulations have changed considerably over the decades.

Despite the frustrating parts of the history, there are also positive, even inspirational, elements. In the category of Individuals Can Make a Difference, here are two citizens who deserve applause:

The dioxane pollution was first reported in 1984 by Daniel Bicknell, a graduate student in the U-M Department of Environmental and Industrial Health and a candidate for Washtenaw County Drain Commission. He took water samples at Third Sister Lake, just east of the Gelman complex, that were tested at the U-M Institute of Science and Technology. His results were met with skepticism by a water quality specialist for the state Department of Natural Resources. “I’m inclined to believe Bicknell’s data isn’t worth a toot. It’s extremely suspect,” the state regulator said. Bicknell persevered, asking for a county grant to study the issue and convincing area residents to petition for water testing. Those results a year later came back positive. Sixteen months after Bicknell’s discovery, the same DNR official had changed his tune, worrying that the initial dioxane might be from just the edge of a plume and greater pollution might be found in other areas, noting, “It’s extremely important we find out.” Bicknell had thought so a year and a half earlier. Bicknell went on to a career with the Environmental Protection Agency, but came full-circle in 2015, returning to consult with local officials on the continuing Pall pollution clean-up.

Roger Rayle is another citizen who has performed admirable public service on this issue for the last 30 years or so. His name is regularly sprinkled throughout the news stories beginning in the mid-1990’s. He is the co-founder and leader of Scio Residents for Safe Water, a watchdog group that has relentlessly monitored Gelman and the public officials in charge of the clean-up. Since the group’s inception in 1995, Rayle has attended countless meetings to gather data, document regulations, evaluate compliance, update maps, and urge more effective and timely solutions. Rayle, also a member of the Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD), told The Ann magazine in its March 2016 edition that his advocacy started after he went to a community meeting about the Gelman pollution and was shocked by what he heard. “I imagine I probably felt like a lot of people who are in Flint do. How could this happen? Why isn’t somebody in charge of this? Why aren’t they solving the problem?” Thirty years later, Rayle is still offering his knowledge as part of the solution.

Additional information: The Coalition for Action on Remediation of Dioxane (CARD) site has maps of the dioxane plume and other recent information. AADL carries "Various reports on the dioxane pollution", by Gelman Sciences, Inc., in the 3rd floor Reference area, which includes documents prior to 2008. The remaining documents are at the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) Gelman Sciences, Inc. Site of Contamination Page.

DEQ proposes tougher cleanup standard to protect residents from dioxane (MLive, March 15, 2016)

Lynn Monson is a freelance journalist from Dexter. He was an assistant metro editor at The Ann Arbor News from 1995 until that iteration of the newspaper was closed in 2009.

A History of the Interfaith Council for Peace & Justice

Since 1965, the Interfaith Council for Peace and Justice (ICPJ) has inspired, educated, and mobilized people to unite across differences and to act from their shared ethical and spiritual values in pursuit of peace with social and environmental justice. The Ann Arbor District Library, in partnership with ICPJ, has pulled together hundreds of photos, local news articles, and documents spanning five decades of social justice advocacy and activism in our community.

From the very beginning, in 1965, this organization (and its supporters) has envisioned a world free from violence, including the violence of war, poverty, oppression, and environmental devastation. The core of ICPJ’s work over the past five decades has come from a number of volunteer-led program areas and working groups. These program committees bring people together from a variety of religions and backgrounds to work on specific peace and justice issues.

In the past ICPJ has hosted working groups focused on the Prevention of Gun Violence, No Weapons/No War – alternatives to military engagement, Common Ground for Peace in Israel/Palestine among many other issues. Recent areas of work have included Racial and Economic Justice, Climate Change and Earth Care, Latin American Human Rights Issues, Hunger/Poverty and most recently a themed year (2015) exploring Food & Justice with a 2016 focus on Income Inequality and Racial Justice coming up.

Please take a moment to explore the rich history of this important social justice organization. Below are some of the themes, work groups, and events during 50 years of ICPJ history in Ann Arbor:

Hunger: Since 1975 ICPJ has organized the annual Washtenaw County CROP Hunger Walks as an interfaith response to local and world hunger. Over the last 28 years walkers from some 50 area congregations and schools have raised more than one million dollars to assist both local and international agencies in relieving hunger and addressing its root causes. ICPJ works closely with Bread for the World in education, action and advocacy efforts; provides resources for congregations and groups doing programs about world hunger; and cooperates with area agencies in raising community awareness and soliciting funds.

Latin America: The Latin American Task Force devotes itself to education and action on Latin America concerns, especially U.S. policy in that region. It stands in solidarity with the movement to close the U.S. Army’s Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (formerly the School of Americas), as its graduates have committed atrocities across Latin America, leading many to consider it to be a “School of Assassins.” The task force also organizes educational programs about the U.S. military presence in Colombia and Honduras and how corporate globalization affects the poor in Latin America. Related events reflected in our photo history are: School of Assassins Watch (SOAW) events, ICPJ's early involvement with the establishment of our Sister Cty in Juigalpa, Nicaragua, and the events associated with the Religious Coalition on Latin America (RCLA).

Dozens of other topics and events are represented in the Photos collection, including annual Hiroshima Day events and Nuclear Disarmament protests; and programs and events associated with ICPJ's Middle East Task Force (METF). You will also find photos of ICPJ's participation in parades, at numerous vigils, and many other local and national events.

Polio in Ann Arbor

People were so desperate to save their children from the dreaded disease of polio, that when the first vaccines were sent to Ann Arbor in 1955, they were stored at the police department in a refrigerator, locked with a chain around it. Just three weeks previously, on April 12, Dr. Thomas Francis of the U-M’s School of Public Health had made the momentous announcement that the vaccine developed by Dr. Jonas Salk, which used killed polio viruses to give immunity, was “safe, effective and potent.”

People were so desperate to save their children from the dreaded disease of polio, that when the first vaccines were sent to Ann Arbor in 1955, they were stored at the police department in a refrigerator, locked with a chain around it. Just three weeks previously, on April 12, Dr. Thomas Francis of the U-M’s School of Public Health had made the momentous announcement that the vaccine developed by Dr. Jonas Salk, which used killed polio viruses to give immunity, was “safe, effective and potent.”

“Vaccine will end polio as a major health threat,” was the headline in the April 12, 1955 Ann Arbor News, shortly after Francis gave his report at Rackham Auditorium. The announcement was made in Ann Arbor because of the key role the University of Michigan had played in the vaccine’s development. Francis, who had earlier developed a flu vaccine, joined U-M’s Public Health Department in 1941, followed the next year by Salk, who Francis had mentored at New York University. Salk left in 1947 for a job at the University of Pittsburgh, where he developed the polio vaccine using tools he had learned from Francis.

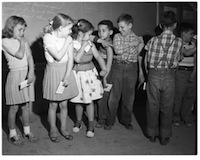

Francis was hired by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (often called the March of Dimes after its major fundraiser) to conduct tests to determine if Salk’s vaccine worked and was safe. Using blind studies so that none of the almost two million children who were tested knew whether they were receiving the vaccine or a placebo, he found that it met both criteria. The children who had received the placebo were at the head of the line to get the real vaccine.

Francis was hired by the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis (often called the March of Dimes after its major fundraiser) to conduct tests to determine if Salk’s vaccine worked and was safe. Using blind studies so that none of the almost two million children who were tested knew whether they were receiving the vaccine or a placebo, he found that it met both criteria. The children who had received the placebo were at the head of the line to get the real vaccine.

On April 11, the day before Francis presented his report, officials from the polio foundation and the scientific world began arriving by train. They were welcomed with much fanfare at the New York Central Station (now the Gandy Dancer). The most important arrival was Salk, who came with his wife and three boys. The two oldest had been born in the old maternity wing of University Hospital, which by an interesting coincidence had been turned into Francis’s evaluation office where he and his assistants did the monumental job of collating the data, which in the days before computers was very labor intensive. Pictures show rows of file cabinets, a card catalog, and piles and piles of papers.

Francis had refused to give any prior information on his findings, not even a hint if they were positive or negative, saying he wanted to make absolutely sure that everything was accounted for. He presented his report at a closed meeting by invitation only. As well as scientists, the audience included 400 reporters. When Francis finished, copies of his report were wheeled in on a cart. The reporters started grabbing them and running to telephones to phone their respective newspapers, magazines, radio and TV networks. A room had been set aside for the reporters with four teletype machines and ten tables with seating for six people sharing three phones. The Ann Arbor News let the AP use their darkroom to send pictures to their wire services.

Three weeks after Francis announced his findings, local children began getting the vaccine. On April 29, 1955, one hundred volunteer doctors began vaccinating first and second graders at thirty area schools. The newspaper was filled with pictures of brave children getting their shots. The 7000 doses were provided by the polio foundation. They arrived at the county health department a few days earlier and were stored at the police department.

The county health department found the money to buy enough vaccine to inoculate the more than a thousand children receiving welfare support, again using volunteer doctors. The rest of population went through their private doctors. The physicians were so overwhelmed with calls that a post card system was set up for parents to send in and even these got so out of hand that the doctors asked that parents only request shots for children at least one year old and not yet in first grade. The decision to start with the younger children was no doubt made because that was the age group most likely to die of the disease. Parental permission forms were needed but hardly any parents refused. In the first batch, out of 804, only ten said no.

Ann Arbor, like the rest of the nation, had been grappling with polio for years before the vaccine. The first mention in the Ann Arbor News was in 1934 when a National Committee of Birthday Balls was organized across the nation on FDR’s birthday, with money earmarked for polio research. The local ball committee included Ann Arbor’s mayor Robert Campbell and the editor of the Ann Arbor News Arthur Stace. In the following years the Ann Arbor News was filled with human interest articles about victims coping with the dreaded disease- a women spending half the day in therapy and the other half learning accounting, a girl playing the piano, a boy able to ride a bike while wearing braces. The public library loaned out a device so sufferers in the hospital who couldn’t raise their head could read on the ceiling.

There was also much fundraising - kids having backyard carnivals or circuses, a bake sale at the hospital, newspaper drives, service clubs like the Eagles taking on projects. The metal workers and the electrical unions made replicas of iron lungs that could be used as canisters to put money in. The March of Dimes was a yearly event when mothers went door to door collecting money, often in dimes. (FDR’s picture is on the dime for this reason.) These articles continued after the announcement of the vaccine, but began to taper off as more people were protected.

Francis died in 1969. Salk, who died in 1995, returned to Ann Arbor twice. In 1977 he was the featured speaker at that year’s U-M Medical School graduation. In 1995, he made another visit, this one on April 12, exactly 40 years after the announcement that his vaccination was effective and safe and at the same place, Rackham Auditorium, to be honored by the March of Dimes. At that time he said his work was focused on finding a vaccine against HIV.

See all Oldnews articles and photos on the history of polio and the polio vaccine in Ann Arbor.